MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

STOL in Juphal is just long enough for take-off's. We meet our crew who had to

walk 10 days to get here from the end of the road. After our first lunch we set

out for Dunai, where we will spend the night.

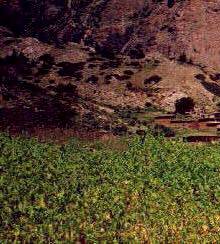

Terraced fields along the Bheri river.

The trail descends from Juphal towards the river. Just after monsoon the valley

is still covered in a light green, after Kathmandu's polluted air the sweet

smell of herbs is a relief.

After the wide Bheri valley we climb steadily through dense forests. The

slippery trails run down at the river most of the time, but there are enough

steep climbs and descends to get some training before the high passes of Upper

Dolpo.

The 'small' Suli Gad is white-water almost the time, luckily the bridges are in

fairly good condition.

The Tapriza school gives children of nearby villages the

opportunity of a first class education. The school is funded by Westerners and

supported by the Nepalese government.

[for further information about the school please get in touch with www.tapriza.org]

Most kids stay at the school the whole summer, Saturday is their day off and

they play games..

Dolpo to Mustang: Nepalganji - Ringmo

Nepalganj to Ringmo

Nepalganj - Dunai (24. August 1999)

After two days in Kathmandu we set out for Nepalganj, a shabby town near the border to India from where most flights to Western Nepal start. After spending an afternoon in sultry monsoon atmosphere I am happy to board the plane the next morning. After a long, long time of waiting our tiny plane takes off, marking the starting point of our trek.

The cloud cover opens up occasionally, swollen brown rivers flow through thick forest. Heavy clouds build up at the first low mountain ranges. Trees grow to the very top, among the terraced fields are small villages that cling to their flanks. For a few minutes we fly right through clouds, there's nothing around us except the bright white of the clouds. This is a bit scary since the plane doesn't look as if it had fancy technical equipment and there are more and higher mountains before us. The liaison officer enjoys that part of the flight even less than I do. Once out of the clouds we approach a narrow valley whose steep walls covered by small forests of conifers growing up the slopes. A river flows at the bottom of the gorge, small paths run parallel high above it connecting the few villages. This could be the Bheri river, which comes from Phoksumdo Lake and Do Tarap, two of the places we will pass on our way. We have left most of the clouds behind us and enjoy the bright sunlight and pleasant views. After a sharp right turn we descend quickly towards terraced fields. They come closer and closer fast. Five seconds later we touch the ground and land on the STOL on a small plateau. The name means Short Take Off and Landing, an accurate description.

The air is fresh and the temperatures are much more pleasant than in Nepalganji. It feels so much better here at 2100m than in the Terai which is only a few hundred meters above sea level. It is as if somebody suddenly removed the plug that was in my lung and I finally get large amounts of fresh air.

A few groups of tourists are waiting and board the plane. We watch in amazement as the little airplane takes off: shortly before the abrupt end of the runway the plane is in the air. I'm happy to fly out of Jomosom; the runway there is quite a bit longer.

Our trekking crew is waiting for us in one of the nearby lodges. They are shuffling and preparing their loads while we enjoy our first lunch by Padam Rai, our cook. Thomas has not expected such varied and delicious food on the trek, and cannot believe me that it will be like this for another three weeks. One hour later we leave Juphal, after a short walk through the town and its nice flat-roofed houses we are in the midst of an abundance of colourful fields. The tints range from yellow and light green to brown, it is truly a great first day of trekking. Rice and buckwheat ears are waving in the wind, young corn is grown and there are even fruit trees. We descend down to the Bheri river whose source is near the watershed that separates it from the Kali Gandaki. If all goes as planned, we will cross the - hopefully much smaller - stream in a fortnight. The valley wall on the other side is very steep and doesn't allow for agriculture, we see only a few goats grazing on the green meadows. Steep walls surround our side of the river, too, but a stretch of relatively flat land between the mountains and the river could be terraced. High conifers grow in the sheer rocks above the fields.

The people have the reputation to be lazy because they don't take as much care of their fields as they should. But the area that can be cultivated is so large that careful plantation would take a lot of manpower. And the maintenance of the terraces requires even more time; rockslides can be seen everywhere and despite their small size they destroy much farmland which has to be re-claimed with much hard work.

After the monotony of Kathmandu, which was intensified by grey monsoon clouds, the play of tints is liberating. A small ochre path takes us through green fields, white clouds on the dark blue sky throw black shades on the hills far ahead. The scenery is fantastic, in addition to the fields even the rock faces shine in an eerie green, small patches of this bright colour grow out of a darker green.

A small Hindu temple indicates that we have not reached the area of Tibetan influence yet, but we are not in an area of orthodox Hindus either. The people are not as religious as their counterparts further north and south, they revere old mountain gods but integrated Hindu and Buddhist deities. One hour later we pass the first prayer flag whose fluttering sound in the wind is familiar and comforting.

The sheer rocks, the warm wind, its sound in the pine-trees and the small paths through what looks like olive groves make me feel like walking in Spain's Costa Brava. Most striking is the sweet smell of herbs. I'm usually not that attracted by such a landscape and I prefer the barren scenery above 4'500 m, but this is a perfect day in peaceful surroundings. It is very relaxing, and starting with such a pleasant and short walk should be a good omen.

Three hours after starting in Juphal we reach the first houses of Dunai, the `district capital'. The town's location in a broadening of the valley is nice, but the village is dirty and not very inviting. Our permits are checked for the second time, policemen seem to make up a quarter of the town's population. They are all very friendly but speak hardly any English so after 3 minutes our conversation runs out of words. I have postcards to deliver to the owner of Blue Sheep Trekkers Inn, which is where we stay. He is near Ringmo where he works as an engineer and supervises the construction of a hospital. I meet his brother instead, and conversations with locals like him are always very insightful. Especially since he has been abroad and has more criteria to measure the effects of recent changes than simple villagers. This is not meant derogatory, but after having seen some problems of the Western society you are probably less likely to embrace everything that comes from `us'.

Dolpo has suffered because the numbers of tourists have steadily declined. They shun the area because of rumours of Communist unrest. Further west near Simikot it really is a big problem, incidences happen daily but the conflict has not afflicted tourists in Upper

Dolpo.

[Check about the latest state of things

before going to Dolpo]

But many agencies do not offer trips to the area anymore. I assume that the high prices for trekking in Dolpo - provisions must be flown in or carried by porters for several days, restricted area permits cost $70 a day, it takes two domestic flights to get here - might be a bigger deterrence than the violent unrest. Nevertheless, Dunai has seen some development in the last two years: There is a phone now, a generator further upstream produces 200 kW electricity (though this is just a test and not publicly available yet), a boarding school and a hospital have been established. A Buddhist monk from Chharka who made his Geshe degree in Dharamsala plans to open a monastery in Dunai to provide education and help in religious matters.

Tonight is the only night where we have to share the camping place with two other groups. They have just finished their trekking but were not very lucky. Their supplies didn't get to Juphal so they started 4 days later and - because of that delay - following the itinerary was impossible and they had to cancel a sidetrip to Saldang. Dawa tells us the next day that their guide used to work as a cook for Sherpa Society, but was fired because he was not good, and more than once did he mislead the other group, because he was never in Dolpo before. I did not pass that information on to the Frenchmen, they were angry enough already. They also had heavy rain every night and almost every day, sometimes it was so bad that they had to camp for a few hours during the day and wait for better weather.

For us so far everything has been very smooth. Everything was ready in Juphal, our cook is world-class, Dawa a friendly and knowledgeable guide with very good English, and the rest of the crew is also nice. The weather was perfect, the scenery was lovely, I cannot imagine a better start.

Dunai - Serpka (Day 2)

It was such a warm night that I could enjoy the luxury of not needing a sleeping bag. After porridge and toast we leave shortly after 700.

The routine will always the same every day; we wake up at 600 and have our first cup of tea. After washing and packing, breakfast is ready some time later. While we enjoy toast, porridge, omelettes, scrambled eggs, pancake, rice pudding, and chapati (this is the menu of three weeks trekking and not that of a single day!) the porters pack their loads and we leave half an hour later. After three hours of walking we stop for lunch. I can set my clock after my stomach, shortly after 1000 I start to feel like I'm starving. The porters are a little behind because the stop for early lunch, the kitchen crew usually walks about as fast we do. Waiting at the lunch spot and smelling the food is always a minor torture. The two-hour lunchbreak allows for interesting excursions in villages or relaxing naps, afterwards it is another three hours to the camp. Tea and biscuits are served around 4 o'clock, a British custom which I have come to enjoy only after three years of trekking. The sun sets quickly and it gets cooler (or even cold, depending on the altitude) soon after dusk. We finish dinner often around 1930, but we are tired and there is not much to do so I am often asleep at 2000 already. Of course this program has to be changed on some days because of weather, possible lunchspots, availability of water etc.

It has not rained during the night and we will walk in warm sunshine most of the day. A good bridge crosses the Bheri; we follow it downstream for an hour until we reach the Suli Gad. This side of the river looks much different than the side we walked yesterday, instead of dense forests and steep cliffs it is hilly, almost treeless and not used for agriculture. Dzos (a crossbreed of cows and yaks) and sheep are grazing higher up where only grass and single trees grow. A large variety of plants grow at the river, flowers in all sizes, shapes and colours; lavender and mint give the air a fresh smell.

The river is very broad but must have carried even more water just recently, the trail has been washed away in many river bends. Its source is the river from the Tarap valley and the Barbung Khola which springs in mountains that form the natural border to Tibet and Mustang. Fine black sand gives it a dark colour. In total contrast the Suli Gad - the river from the Phoksumdo lake - is light grey, which gives the confluence an odd colour mix.

We will follow the Sali Gad and the narrow valley for the next two days until we reach Phoksumdo, a likely highlight of the trek. The path runs along the river, again the landscape changes suddenly. The vegetation and reddish rocks remind me of the valleys and canyons at the Californian coast. It's also rather hot, the clouds that are piling up on the southern ridge and towards the north seem further away than they really are. There is another route higher up which passes through two villages, but they are said not to be worth the extra effort.

The trail is in a good condition, but needs to be maintained all the time. The villagers are responsible for `their' trails, when they need building supplies like thick ropes or steel cables, the government provides it for free but all the work is unpaid. The stones are broken out of the rock, hammered and cut in the right size, carried on people's back to where they are needed. Halfway to our lunch spot we meet three men who carry those rocks to a `nearby' construction site. This is incredibly hard work and now it becomes clearer why being a porter for trekkers is not the worst job one can have in Nepal.

The creek is almost completely whitewater, small rapids follow small rapids. Three hours after leaving Dunai the valley becomes wider, in the middle of it lies Yara, a tiny village with pretty houses that have flowerbeds on their roof. Just below it is a watermill where corn is ground into flour. The water is diverted far up and brought to the mill in a small channel. Through a hollow trunk it falls on a horizontal water wheel which is directly connected to the millstone in the building above it. The turning of the stone shakes the funnel and releases the grain which then falls into in the hole in the middle of the millstone. Only the filling of grains and the collecting and packing of the flour must be done manually. The miller is just coming down from the village and seems to be proud of his neat and clean millhouse. I get the impression that he is more satisfied than the millers in Upper Mustang, who belong to the ethnic group of Garas and are considered lower class.

A few dzos are grazing in the small forest near the stream, the wide horns give them a dangerous look but they are rather shy. Two boys collect dry wood and tear off small branches from the few remaining trees. Deforestation is a problem in Nepal, quite a number of landslides and loss of fertile land could be prevented if there were enough trees. The problem has been recognised and some re-forestation programs have been started, tourists (who were responsible for a small amount of wood-consumption) are also more aware and the situation seems to improve. But if we Westerners were really so concerned about the environment we should ask ourselves `where does my electricity come from' more often instead of critising some farmer in Nepal who simply has to cut down a tree to cook his meal, or has to collect firewood because otherwise his family would freeze to death in winter. When you have heating, electricity and hot water at your fingertip all the time it is very easy to complain about deforestation and people's shortsightedness in a distant country!

We steadily gain altitude while walking through fields of flowers and high grass. The trail disappears completely in the manhigh bushes, it is a funny sight to see only a row of baskets walk through the field, and the porters who carry them are invisible. Down in the gorge the river roars louder than before, the amount of water flowing in such a narrow river is incredible and the rapids become bigger and bigger. From a hill with a stupa on top we look down on a flat area on which a dozen prayer peak out of a green jungle. This is one of the winter villages of the people in Ringmo, now completely deserted. Weed grows 3 meters high and the grass on the roofs does the rest to completely hide the houses. The village is even hard to detect when we walk right through it! This is one of the funniest towns I have ever seen on all of my Himalayan journeys.

We continue to walk high above the river, after one hour we slowly descend into coniferous wood and cross the river over a solid bridge. Plants and undergrowth become denser here, the path is muddy and slippery. We have to walk up and down more often, as you would expect from walking in a jungle. On one of the few clearings is an old hut which uses a big overhanging rock as part of the roof, a nice looking construction that was used as campsite before. One hour away is a newer and nicer campsite. The plateau is just large enough for some cornfields and a large house. We will spend the night in Serpka. We've just arrived in time to watch a downpour while sitting in the kitchen in an adjacent hut. It is a really simple kitchen, an earthen oven is fired by wood beneath it, and something is boiling in the two pots. The cupboard is filled with a few jars of jam, sugar, a toothbrush, some medicine and that's it. A gurgur, which is used to make butter tea, indicates that we have reached the Tibetan culture. I decline offers to have a cup of Söl-cha (salt-tea) - not because of its taste but because I am extremely careful (read: paranoid) and afraid of stomach problems.

The rain is pretty strong and it must miserable for the porters, the trail was slippery enough before the rain - and we walk in hiking boots and not plastic slippers - and their only protection is a piece of plastic sheet. Luckily they arrive not much later, their speed and endurance is really amazing.

The house has been built recently with the purpose of serving as a guesthouse in mind. We get to enjoy dinner under a rainproof roof on the first floor with a nice view of the river and the valley. The rain must have been exceptionally strong further north; it has changed the colour of the river from a light green into a dark brown within just a few minutes. Mist moves slowly down towards the valley floor, gradually hiding the trees behind a grey haze. When sitting over tea and biscuits in the dry it is very comfortable to watch, walking in that moisture would be something quite different. At dusk the fog is gone and so are the clouds. When you sleep in tents and have to walk the whole day, it is very comforting to see a few stars on the sky when you go to bed.

Many local people on their way also stay here for the night. A few girls from Pungmo arouse interest and a bit of excitement in our crew. The didi (manager of the guesthouse) was making apple brandy this afternoon, plenty of it is available and I expect to hear singing until late at night. The porters last year took every chance to dance and sing all night long, yet the next day they were always in good shape. This year's crew seems to be more serious or maybe it has to do with the fact that playing instruments is not allowed in national parks, but while dozing off I only hear laughter and chattering but no music or dancing.

Serpka - Sumdwa (Day 3)

It hasn't rain during the night for the second time, are the summer rains finally over? But heavy clouds cover the sky and more are coming from the south. As soon as we start walking a light drizzle begins, my raingear keeps me perfectly dry but this does not improve my mood. After the checkpoint we are in the forest again. The scenery is similar to yesterday afternoon: dense forests, ferns, bamboo, moss-covered stones, but surprisingly few birds or other animals.

The climbs and descents become steeper and more frequent, but are rewarded by great views on waterfalls far below. Very tall conifers block the rain, the fallen needles make the trail soft and pleasant to walk on. But slippery stones ask for attention, especially when walking on small ledges high above the river. The previous week a kitchen boy of another group fell down, he managed to let his basket go just in time to grab some bamboo. At one point it goes straight down 30 metres, at some curves the trail goes over piled boulders which serve as a foundation. It does not look very stable. The bridges are generally in good condition, only once do we have to cross one that stands precariously tilted and is very slippery because of the spray.

After 1½ hours the trail goes straight uphill for a long time, taking us out of the forest and over a pleasant meadow on the upper valley wall. After the various greens of the jungle it is a welcome change to walk through colourful flowers and fields. The slight rain which has fallen on and off the entire morning has stopped and the sun seems to break through the thin clouds. It is frustrating to see how it gets brighter and brighter but starts to rain again eventually. Yet at the same time this is what makes trekking so remarkable: life is temporarily cut down to basic things like weather, food, sleep, and health. It is stunning how fast you get used to this "reduction". I know that this simplicity probably would not satisfy us Westerners for very long, but it is a good experience which I am often remembering. It also makes me appreciate the luxuries I have back at home. Even though the river is far down no attention is required because the path is flat and broad now - thoughts can wander freely.

The lunch spot is down at the river, we stumble down a steep and muddy trail once again. How the porters with 30 kg on their back get down these slopes without slipping is incredible. The constant up's and down's have made me a little tired, but I know that I need two days to get in shape so I am not worried.

The bio-diversity in the Himalayas is surprisingly large, particularly in the valleys in north-south direction that get much rain in the summer. The disadvantage is that trails are often in a bad condition: taking this route in July seems impossible. Rock and mudslides destroy all human efforts. The summer trails higher up are more strenuous and only taken when absolutely necessary. It is easier to follow the trail near the river, which is possible only because the water level has decreased in the last few days. The slabs along the shoreline are an inch or two higher than the torrent.

After twenty minutes of trying not getting wet feet the river becomes broader and relatively calm. The valley also opens up, many pine-trees grow and would make this a perfect picnic spot if it were not for - yes you guessed right - the rain. We have lunch under an overhanging rock to escape a heavy downpour. Although rain has not been bad so far - just occasional and short drizzle - it also seems to influence our crew's mood. After a sparse meal we set out again in less rain, the scenery is the same as in the morning but less strenuous because we walk closer to the river and have to climb across side valleys less often. A few smaller creeks contribute to the Suli Gad, whose colour has turned from the light grey it had yesterday to a light green. It is very surprising how few animals we spot. We are on the main route to Ringmo, but that the few people scare away all birds and other animals seems strange.

All of a sudden the colour of the river turns into a darker green. We are at Sumdwa, where the Suli Gad from Phoksumdo and the Pungmo Khola from the west meet. This is the place of military post and - probably more important - the Tapriza school. Marietta Kind, a Swiss ethnology student who spent 1½ years in Ringmo, helped establishing the school. She gave me some letters and postcards for two teachers. Senduk Lama has some time to show me around. 43 children from Ringmo, Pungmo and a village further west get their education here. The school is quite successful in its second year, but the beginning was difficult. Parents did not want to send their children to school because they did not understand the value of it. But now parents are happy, and after hearing their kids speak English those owning restaurants and guesthouses suggested that Tibetan should be dropped and more English be taught instead. Even the younger pupils speak good English, and I'm relieved that they understand my Tibetan. So it cannot be that bad. Of course Nepali is also taught, in addition to math, Buddhist culture and handicraft. Since this diverse curriculum with much emphasis on local culture certainly does not promote the `hinduization' as envisioned by the central government in Kathmandu, I'm surprised to hear that the school gets a little government support nevertheless. Needless to say the 4 teachers are more motivated than the teachers who are usually sent to rural schools by the government. Often they are Hindus, used to life in the lower parts of Nepal, e.g. the Kathmandu valley. Suddenly they find themselves in a harsh climate amongst a culture they do not really understand and sometimes even see as inferior. Often they leave before their time is up, and they never stay longer than they have to.

I hope to meet Senduk Lama at Ringmo again. Tomorrow is full moon and people have asked him to hold a puja. The prospect of seeing a Bon ceremony is certainly enticing. I will not understand much, but I might receive profound explanation afterwards.

Since the porters could not cook with firewood near the checkpoint, we camp halfway between Sumdwa and Murwa. I'm not unhappy to stop here, it rains a little and it has been good but tiring walking. A lonely house is just being built, it looks like a future guesthouse. So far only one part of it has a roof, in the smaller room the kitchen crew sets up their stuff, in the other one lives an entire family. The fire is the centre of the room, in the far corner an old, old grandmother (or more likely a grand-grand-(grand?)-mother) is sleeping and after waking up takes care of a 2-year old girl. Her mother is making rakshi, strong liquor out of wheat. Several pots are set on top of each other, the cracks are sealed with clay. The lowest pot contains fermented wheat, by heating it the alcohol rises. The third pot contains cold water and when the alcohol reaches that bottom it condenses and drops into the middle pot. At least that is how I imagine it works, maybe I am wrong.

Nearby the groundplan of another, much bigger building is drawn with chalk on the ground. When the hospital is finished it will offer Western medicine as well as Tibetan and herbal medicine. WWF is supporting the study and collection of herbs around Ringmo, I assume they also finance this project.

Everybody here is really friendly and we have a good time playing with the kids. Despite the rain that has hit us harder than yesterday this was also an enjoyable day, mainly because I've spent more time with local people.

|

Summary Part 1:

We leave the monotony of Kathmandu and the shabby Nepalganji behind us and are finally on our way to Dolpo. After an adventureous flight and an even scarier landing we start our trekking in Juphal. On the way down to the Bheri river we pass through the fields, the abundance of colours and smells remind me of the Mediterranean. Soon afterwards we walk in dense forests in the Suli Gad valley. Steadily gaining altitude on slippery trails, we leave the 'low lands'. Our first highlight, a village called Ringmo, is only one day away. |