MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

The old fort and monastery on Namgyal peak overlook the bazaar and old part of

Leh.

The fertile side valley of Changspa with Namgyal peak.

View from Namgyal peak towards Sankar, Nubra valley lies behind the snow

mountains.

The ancient fort in the morning sun.

The Indus Valley with the Stok range and its heighest peak.

Tikse monastery is in easy reach of Leh and worth a visit.

Silhouette of Tikse and the monks' houses below.

From the roof the views over the fertile valley and the arid desert are

stunning, Stagnak gompa on the hill in the middle.

The large statue of Maitreya in Tikse.

Mathok gompa stands on a ridge overlooking the village, the Stok range rises

behind it.

Afternoon picture taken from Stagnak. Tikse monastery stands on a hill in the

right, Indus river flows towards Leh.

Tso Moriri: Delhi - Leh - Shang Sumdo

Delhi - Leh - Shang Sumdo

Delhi - Leh (27 September 2002)

Once again I’m off to the Himalayas for a trek. Deciding on the destination was easy: Nepal is in turmoil and this itself wouldn’t deter me, but there are not many expeditions happening because of it. Ladakh is equally beautiful and luckily Jamie and Joel lead a trek through a more remote part there. I've been trekking with both of them before, they run a virtual trekking agency www.project-himalaya.com and often have trips with special routes for connaisseurs, and always a superb crew.

I arrive in Delhi shortly before midnight from Zurich, despite SARS get quickly through customs and find the people from Druk expeditions who bring me to a close-by hotel. Soon it's 4.00 in the morning; I wake up just before the alarm rings, pack and go for breakfast. The receptionist is huddled on the couch, gets up to fix breakfast and will probably be asleep again in five minutes - typical Indian work hours. I'm supposed to meet the two other trekkers here and we'll fly together to Leh and meet Joel some days later when he returns from another trek. Bob Rosenbaum was in Kangchenjunga and we've been briefly been in touch by email, Lance decided to join in the last minute when he met Jamie in Kathmandu. Malc from England will join ten days later.

The sun is an orange disk shining over a hazy green plain when the airplane takes off. Twenty minutes later we're above the middle hills of Lahaul which are densely forested and sparsely populated. The ridges of Himalaya’s foothills throw bizarre shadows. Very quickly the scenery changes; the southern slopes are still green, the northern faces are either barren or snow-covered. Soon there is an immense snowfield beneath us, a huge white area with hundreds of peaks and dozens of glaciers. A few stupendous massifs at the horizon tower over these lesser peaks. Four mighty ranges meet in Ladakh: the Karakorum and Ladakh range to the north, the Himalayas and the Zanskar range in the south.

The airplane makes a sharp right turn; its left wing hides a huge summit that must be one of the giants of the Karakorum (K2?, Masherbrum?). To the right lies Tso Moriri, our destination after two or three weeks of hiking. After a left curve we enter the Indus valley where ochre hills and mountains run parallel to the wide riverbed. Poplars follow the green stream at each bank, whitewashed square houses stand out between the harvested yellow fields. Higher up in the side-valleys, partly hidden, are more villages that can only exist thanks to their efficient usage of glacial water and the skillful construction of fields in the alluvial fan.

One last skilful manoeuvre above a ridge, then the pilot takes a 180° turn, 'passes' a monastery that clings to a precipice (Spituk, the first Gelugpa monastery at the edge of the 'Tibetan empire') - and we arrive in Ladakh. Blue sky, warm sun, no wind - the announcement 'Leh, outside temperature 3° C' comes as a surprise. If it's that cold in perfect conditions, how chilly is it going to get higher up in nasty weather in two weeks?

After an absence of 1½ years I was wondering how it’d feel to be back in the Himalayas. As the airplane door opens and I walk down the stairs I know I’m still as excited as ever. The air is crisp, just the smell evokes both memories from past treks and images of the coming one. A jeep picks us up and drops us at the Highlife restaurant, situated ten minutes from the town’s centre. For a few days we'll stay in the lodge right behind it. It's a new guesthouse, built between poplar and apple trees, flowers grow at the porch - a relaxing place. In Changspa, the houses would be more traditional and I could stay with a family, but it’s not worth moving for just two nights.

I lie down for a few moments in the room, after putting on warm clothes. I breathe in the cold air, watch the shadows of apple trees dancing on the ceiling and listen to birds chirping in the orchard until everything becomes blurry and I doze off. After a relaxing two-hour nap I stroll around town.

Knowing a little about Leh's past makes it easier to understand Ladakhi culture. People are outgoing and interested, yet think carefully and rationally before adopting western amenities. For hundreds of years trade routes from Persia, Mongolia, Tibet and China have crossed here. Though it was never a major part of the Silk Road, it was the most important southern branch to Afghanistan, Pakistan and western India which did have a large economical and cultural influence on Leh. Trade started to become less substantial a hundred years ago; still the atmosphere of these past days is tangible in the bazaar. If I'd have to characterise my first impressions with one word I'd say: civilised. It is more civilised than any other city on any Friday morning I have ever seen. People in the bazaar are humorous, courteous, self-assured and content.

The time I spend in town is short; I restrain myself from too much activity on the first day since my body needs some time to adapt to the sudden jump of altitude of 3'300 meters. And there's plenty of time; I have at least two more days in Leh. Joel and Jamie should be on the way from Zanskar and arrive in the next days.

While enjoying another nap I hear familiar voices. After some worrying seconds I realise with relief that the voice was not part of an erotic dream, and get up to greet Joel who is here in person. He arrived with Nicole, both decided to skip the climb of Kang Yaze that Jamie and two others are attempting right now. We have early dinner together, delicious Indian food. The tourist season has come to its end. The cold temperatures are noticeable while typing some emails. Temperatures start to drop below freezing point at night. My body will adjust to the cold after some days, though a better sleeping bag would be nice. Lobsang - our local guide - knows somebody who sells Indian Army sleeping bags at very reasonable prices.

Lobsang is a friend of Joel, the two have been trekking together numerous times. Born in a nomad family, his adventurous life has brought him to the military (some good stories there what they did on the Pakistain border) but eventually he left to become a guide. He also skipped the climb and came back two days early with Joel to help organise things for our trek: buying food, organising the jeep rides etc. He seems to be a boy from the countryside who loves nature but also knows to enjoy the more tempting things that the city offers.

Leh - Tikse - Stagnak (Day 2 + 3)

I slept well, except for a dream in which I developed the computer program for vote counting in the Kashmir district - and modified it to make the Ladakhi win over the Srinagari. Strange dream, but at least I'm here with my thoughts, and not back at home.

Though it is cold in the unheated room, I'm cozily warm under the two blankets and wake up to singing of birds in the orchard. It's equally freezing cold in the shade, but in the sun it is quite warm already. The morning sun radiates a warm orange light that increases the stunning colours - a wonderful morning for a little walk.

Skipping breakfast, I slowly climb the hill above the old part of town and hike up towards the old palace. It was built in the 17th century by Senge Namgyal, the most powerful of the Ladakhi rulers. He conquered Guge in Western Tibet and Zanskar, but was defeated when advancing westwards to Muslim territories. The foundation of many monasteries is attributed to Senge, though his policy of isolation brought the lucrative trade on the Silk route to a halt after his death. His son’s quarrel with Lhasa led to invasion from Tibet that was only fought back with the help of Ladakh’s western Muslim neighbour. The price for help was conversion to Islam and the construction of the mosque in the bazaar. What looked like defeat turned out to be a blessing: people weren't forced to become Muslins and remained Buddhist. Not being part of Tibet saved them from the Cultural Revolution and the other atrocities that China inflicted on Tibet 350 years later. The palace that has witnessed turbulent times lies in ruins now, nevertheless it is still an impressive building that looks like a miniature of the Potala in Lhasa. Though it is empty, it'd be interesting to have look inside but it is locked, like the Chamba Lhakang - monastery of Avalokiteshvara. In the other monastery below the palace, an old monk is shaving in the courtyard. He seems a little burned-out from the tourist-season and tired of having to watch over the monastery, but is nice enough to fetch the key for the ancient locks to the door of the assembly hall.

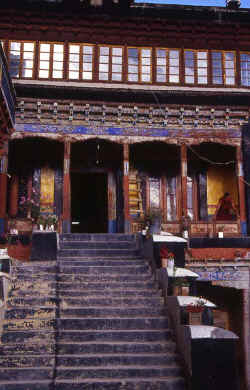

The mural paintings are beautiful and distinctively Tibetan in style. It seems true that the only places with the detailed Kashmiri paintings that survived times and invasions are in Alchi. On top of the hill stands Namgyal Tsemo, the monastery of protective deities that was built by Tashi Namgyal, father of Senge Namgyal. The monk warns me that nobody will be up there, but it is a nice viewpoint and little hike won't hurt acclimatisation, so I follow the little trail upwards. Prayerflags are flattering between the top of two hills, spanning 50 meters to the compound on top of Namgyal Peak. Colourful flags lead to the red and white monastery that stands out against the dark blue sky. In the other direction, the mountain views of the Stok range that rises high above the Indus river are as impressive.

The monastery is topped by the ancient fort, whose commanding position over the nearby valleys must have been a terrific display of power in the - not always peaceful - earlier days.

After an early lunch we all meet for some sightseeing in the Indus valley. The number of monasteries is incredible. Since most have been built around the same time and are of the same Buddhist school – Drugpa, a special branch in the Kagyu tradition that was widespread in Bhutan is prevalent, though some are Gelugpa these days - visiting all of them is impossible. Tikse and Stagnak are in easy reach and we hop in the back of a small Sumo jeep to drive the valley upwards.

The monastery of Tikse stands on top a natural rock pillar and overlooks the village that lies in the flat valley. In between are the small houses of its monks. From the monastery’s roof the view is fantastic: the wide fertile riverbed, following on both sides are stretches of desert that end in the steep flanks of the mountains. Across the river, situated on a ridge, the white monastery of Mathok stands out against the black rock of the Zanskar range that rises behind it. The village is hidden in the poplar grove below whose yellow colours mark the oasis in the desert.

The large assembly hall of Tikse is being renovated; the craftsmen working on the wooden pillars and ceiling are from Nepal. The tallest room features 25 feet tall statue of Maitreya, the future Buddha.

A very narrow bridge takes us over the Indus river to another monastery. Stagnak is also built on top of a hill, though much closer to the Indus, and overlooks the valley in both directions. Just the building itself looks stunning, the massive walls and square shapes are simple, but neither clumsy nor simplistic. To my knowledge Stagnak translates to ‘Black Tiger’, but the name might have come from the founder of the Drug-pa sect. The main prayerhall is less dark than usual; the arrangements of the seats and altars are also more innovative than in other monasteries. Fine statues and paintings are displayed, in a 'storage-room' behind the altar at the far end are old statues. The library contains so many books that they are stored in a separate room that faces the Indus river. The abbot fled Bhutan over political quarrels with its King some decades ago.

From the roof the views are incredible: to the north lies the Ladakh range where barren rockfaces end in snow-covered crests. Poplars trees at the bottom of the rising faces indicate settlements – oases in a hostile desert. The mountains of the Stok range in the south consists of dark rock, above the sheer faces some snow clings to the flanks. On a protruding ridge stands a white cube, Mathok gompa. The contrast to the fertile Indus plain couldn’t be bigger, the setting sun increases the saturation of the colours of blue water, yellow fields, green poplars and willows, and the white cumulus clouds that float in a sky above the snow peaks.

The setting sun makes the drive back to Leh chilly, yet the fantastic atmosphere is worth the few minutes of shivering.

Leh - Shang Sumdo (Day 4)

I am not woken by the muezzin's call this morning, maybe an indication that a strike is really happening today. I lie in bed for a while before getting up, enjoying the warmth of my bed and the fresh cold air in the room.

So far I have not really been in the bazaar yet, after spending time in the main road the little side alleys leading to the old part of town are very interesting. Behind the mosque - a tribute that had to be paid by a Ladakhi king for his bold and unsuccessful attempt to overthrow his Muslim neighbour - runs a little trail that leads to the old part of town. After passing an ancient willow tree that is revered by Sikhs, the 'Kashmiri part of town' begins. The ground floor of a dozen houses is used as bakery, the rooms have been completely blackened by the fume that must have come from the clay ovens for dozens of years. Kashmiri men with moustaches and curly hair roll white dough into balls, flatten and slam them against the inside wall of the round oven. When the bread is baked it doesn't stick to the clay anymore and can be picked up easily. Another business mainly in Kashmiri's hands seems to be fruit and vegetables markets. The owner sits in the middle of his colourful ware like a king on its throne. Most vegetables look familiar, but there are a few whose colour or form I have never seen, let alone eaten, before. The more exotic fruit are brought up from the Srinagar valley, yet the variety that grows at 3'500 m is still impressive: potatoes, barley, apricots, pees, apples, cabbage and carrots can be found in most private vegetable gardens around Leh.

The different crafts are concentrated in one area. The workshops of the goldsmiths are in an alley parallel to the main bazaar. A craftsman - or better artists - with Central Asian features sits next to an open coal fire in which he puts a large golden amulet. With a little pipe he heats up the coals to melt the part of amulet he wants to work on next, then he takes out the softened golden metal with tweezers and works on it until it has cooled down and needs to be melted again.

In Buddhist culture there exists no caste system, yet traditionally some professions were considered 'impure', one of them blacksmiths. The origin might be the belief that local spirits inhabits the ground - often snakes called nagas - and digging for precious metals or stones will wake them, and bring havoc over villages. And if digging is sacrilege, working with ore cannot be virtuous, either. Two hundred years ago, 4 artisan metalworkers from Nepal came to Ladakh to construct large Buddha images for monasteries. The descendants from the same four families live in Chiling and still today produce brass and copper ware of outstanding quality. I assume the goldsmiths have a similar story and immigrated from other areas. Lying in the middle of the trade route had one disadvantage: the easy access to goods of great quality made it unnecessary to develop local handicraft.

Another profession that is looked down on are butchers. None of the butchers and animal traders have Ladakhi or Tibetan features.

Beauty salons and hairdressers are frequented by men and women alike, the owners seem to come mainly from the lowlands. Interestingly, tailors are both Ladakhi and Kashmiri, men and women. Shoppers know what they want: both rich Ladakhis from Leh and poor nomads from the endless Changtang plateau go from store to store to compare before buying. They examine the quality, talk to tailors and then go to the next store to inspect dresses.

In the bazaar people greet each other with 'salam aleikum', outside the bazaar people usually say 'julay'. Is it all as harmonious as it seems at first? Though there were bitter arguments and even fights some years ago which cooled relations between Buddhists and Muslims, the two groups have since then lived together peacefully again.

All these groups of people and their skills have a long history, and I'd be surprised if the main bazaar looked much different a hundred years ago. Hopefully the current generation will value old tradition and learn new skills. This has been such a metropolitan place for centuries that people seem well prepared for future challenges. Contact with outside influences seems to have increased people's confidence in their own skills and culture.

Finally we board the jeep in late afternoon. Our luggage goes on the roof, some of it is squeezed in the back and Lobsang lies on it, two of us sit in front and four in the back. The drive is comfortable, the views beautiful: snow summits rise on our right, barren ranges to our left; yellow poplar and willow trees grow on the banks of the wider Indus river.

Our route takes us near Ladakh's largest and wealthiest monastery in Hemis. After crossing the river on a steel bridge we take a small, unpaved branch that follows an empty riverbed. The valley narrows and turns into a gorge that is dominated not by its shape, but by its orange and red colours. Vertical layers of rocks reach high into the sky, displaying the power of the tectonic plates' clash. Red bushes and small yellow trees grow between the white pebbles of the riverbed. The walls are so ragged that some spots glow like gold in the afternoon sun, while the rest of the walls are already in the dark shade.

After a right curve in the valley we reach Shang Sumdo. Our tents are already put up below the village. I hear women singing, a traditional occupation during harvesting, which still seems to be going on here. The barley in the fields has already been cut and brought to the village where the ears are laid out on a flat spot for thrashing. To separate the sheaves from the corn, three horses and a yak tied on a long stick walk in a circle over the crop. After some rounds, the grain and straw is shovelled into bags for further processing. Hay serves as fodder for the animals in winter. The corns are later picked up and cleaned, before being further processed into tsampa, which together with potatoes makes up the staple diet. The agricultural season is very short and must be finished before frost and snow arrive unexpectedly. Therefore work goes on well after dusk.

In the meantime we’re getting ready and enjoy the cosiness and warmth of the low dining tent. For once not on the standard tables and chairs, but a more innovative idea: We sit on carpets on the floor in foldable chairs, what seems uncomfortable at first turns out to be both warmer and cosier than the traditional dining-tents. Our first dinner is delicious: a fresh salad as a starter, followed by dal baht (lentils and dal) and palak paneer (Indian cheese in spinach). As much as I admire the great explorers Tilman and Shipton and wish to have travelled with them, our different opinions on the necessary quantity and quality of food would have led to altercation on the second day. Jamie does the entertainment today, telling funny and gruesome stories from above 8'000 meters and the recovery of a dead body from Cho Oyo for which he got good money from an insurance company.

When I go to bed the stars and the Milky Way shine brightly. It is cold, which I'm happy about because I'm curious to see how warm I'll be in my Indian Army sleeping bag.

|

Summary Part 1:

After a fantastic flight from Delhi I arrive in Leh where crisp mountain air greets us at 3'500 meters. The views are stunning: the wide fertile riverbed, following on both sides are stretches of desert that end in the steep flanks of the mountains. Across the river, situated on a ridge, the white monasteries stand out against the black rock of the Zanskar range that rises behind it. Some easy walks in the city and up to surrounding hills offer both nice views and easy acclimatization. Temperatues are dropping to 0° C at night, but temperatures during the day are perfect. After staying three days in Leh and visiting some monasteries, we drive to the starting point of our trek in Shang Sumdo. |

||

| (c) 2006, Carsten Nebel |