MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

Shering Gompa lies at the upper end of the Tarap valley. Unfortunately, we find

nobody to let us in.

Houses are scattered admist the fields, an exception is Kagar which is built on

a gentle hill overlooking the fields.

View from Kagar towards north where we came from.

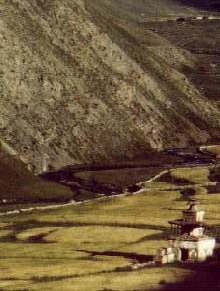

A chorten before reaching Do, a small village which lies at the foot of barren

hills.

Early morning view from the monastery above Do towards the north.

View from Do up the Ship Chok valley. The combination of sunset and a

thunderstorm illuminates the valley in a strange way.

The village Ship Chok, half an hour above the main valley.

We leave the Tarap valley behind us and continue to Charkha. Another pass is in

front of us, a small path on the gravel slope leads to the ridge.

The view from the pass towards the Charkha valley.

Black slate mountain near the pass.

Arid hills in ochre tones stretch to the horizon, some are high enough to have

glaciers on their tops. Small bushes grow only along the rivulets.

The area is densely populated (relatively speaking, of course), very often we

pass the brown tents of the shepherds.

Many families from Charkha spend the summers on the pastures with their animals.

Twice a day the goats are driven down to the tents to be milked.

Dolpo to Mustang: Do Tarap - Charkha

Do Tarap to Charkha

Numa La – Do Tarap (Day 11)

It is very foggy and the heavy rain softens to a drizzle only after we have reached the pass, the 4th one above 5’000 m. Because of thick mist we cannot see more than 70 metres most of the time. After the 2-hour climb I reach our 4th pass above 5'000 m. I was hurrying, not that the speed pays off in any way, on the contrary. A thin layer of snow covers the ground, the cold wind does not invite to stay long at the top. The first porters leave while I wait for the others. The few erected stone pillars make this place seem even lonelier than it already is.

Yellow fields and a few houses appear out of the fog for a few seconds, letting us guess how great the view would be. It has started clearing up and halfway down we see the rugged mountains that stretch over a great distance from north to south. The pass we probably should have crossed yesterday is to our left; a small stream comes from that direction and disappears between the yellow fields in the flat valley further down.

The view of Tokyo and its fields lets us forget the miserable morning quickly, we are excited again and could go on without lunch, but the prospect of a big portion of rice and lentils does not sound too bad, either. We have climbed and descended over 2’000 m and this shows in my appetite. On the other side of the river is Shering Gompa. The monastery is built on a plateau, a fascinatingly unpretentious building with a simplistic yet effective architecture. A villager from the nearby hamlet left five minutes ago and now nobody is here to let us in the monastery, but the small detour was worth it nevertheless.

We are in no hurry and stop quite often, enjoying the easy walk through the golden fields in the wide and long valley. I expected Do to be one big village surrounded by fields. But instead of a single settlement the houses are spread in the whole valley, often in groups of two or three closely built next to each other. According to the map there should be a few monasteries, but I see only the fort-like houses.

A woman invites us into her house and unexpectedly I find myself not in a stable but in an assembly hall. It does look a bit poor and does not seem to be used often. The room is not well cared for and instead of Thankas cheap paper copies are hang up on the joists. Nevertheless it features a large and fine statue of Buddha Maitreya.

After passing a few more houses and chortens we reach an elevation with a village atop. The houses are built above light green terraces that rise out of the yellow fields and barren ochre hills behind it. Even Kagar’s chortens are more colourful than usual, the auspicious Buddhist symbols and luck-bringing elephant are painted in red colour on the whitewashed surface.

The shade of clouds is making the scenery even more interesting. A complex far down in the valley glows in front of a dark hill. Just below this gompa lies Do where we will camp on a flat meadow near the river. On the way there we pass through the valley’s school and health clinic, both are sponsored by the French government. At first I think the school is a monastic one because the school uniform has the same red colour as monks’ robes, but is a normal school that is open to anyone. If the donors spend as much on books and good teachers as they do on sport and leisure equipment (badminton, soccer balls, balloons) then the school must be excellent.

It is Friday afternoon and we catch up with some children who are on the way to their villages. I wonder if they go home every night or just on the weekends – as in most religions, Saturday is the holiday in Nepal and Sunday just a normal day. After overcoming their shyness they are curious and we have a great time talking in English and Tibetan. Time runs fast, our entertaining companions keep me very busy and without really noticing it we reach Do, the centre of the valley.

The afternoon has been offering great views - large barley fields, nice chortens, pleasant villages, farmers at work – and the morning is forgotten. The gompa above Do is a worthwhile site to visit which overlooks the valley and its endless fields. One also sees what is going on in the villages. I notice a big assembly on one of the fields. Nobody is at the monastery and I am too tired for further strenuous climbs.

Two dozen men have gathered, their age and appearance varies, some look like young Khampas with purely Tibetan faces and the typical red strings of wool in their hair, some look like old monks with a shaved head, some have long hair or plaits, some wear traditional clothes while others prefer jeans. They sit in a circle around three men behind a low wooden table with jar and a vase filled holy water. Two of them have long hair and wear a chuba, they have the appearance of lamas, and the third man looks like a normal villager. I suppose I am watching a court session, the only woman is sitting in the middle, complaining and arguing with the three men. While they discuss the issue, some throw in their two cents of wisdom, and the woman leaves dejected. After handling this serious matter the normal village session resumes, the three men do not voice their opinion as often as before and merely seem to be organising and directing the discussion. Every third comment seems to be a joke, there is much laughter.

Many children followed their fathers or uncles but are not interested in the talking at all – which is understandable. The babies are cared for by their fathers, the older kids are bored and since I am the biggest attraction they teach me a game. Eventually this results in an alternative assembly, the kids’ meeting. At times ‘we’ are much louder than the village assembly, I feel slightly embarrassed but I seem to be the only one, the villagers pay hardly any notice.

The sun is setting and turns the side-valley to Ship Chok into a fantastic light, far away lie snow-covered summits, the ochre range in front of it is brightly lit and the ears shine golden, while the another range is pitch dark.

It is almost time for dinner and the assembly also slowly dissolves. I take a detour to our camp because the direct way passes through the back entrance of a house and I noticed a big mastiff there when I went up to the monastery. I have a huge respect, you might also call it fear, those dogs dogs really deserve the name watch dog. Shortly before dusk a large flock of sheep and goats arrive from the pastures. They spend every night near the village, probably because of wild animals and because it is easier to milk them here. The Tarap valley is the liveliest place so far, much busier than Ringmo. It is worth spending some time in the valley, at least we will be here another day.

04.9.99 Do Tarap

We have not yet decided what to do on our free day. We could sleep in but shortly after 700 I am already in the village. The sun shines so fierce that staying in the tent is too hot. The houses are still in the shade the smoke that is coming out of the roofs increases the quiet and sleepy atmosphere. Not much is going on in the village. Quite a few houses are locked up, I suppose people are away on trade or watch the cattle in the pastures. I was surprised about the absence of people my age, there are many children under 12 and people over 35, but the generation in between is completely absent.

Once again I walk up to the Nyingmapa monastery from where the views of the valley are splendid, somehow it looks much different than yesterday afternoon. I am about to climb further uphill in hope for even better views - Thomas has had the same idea and is a few minutes ahead – when I recognise a man coming from the fields below as one of the three ‘leaders’ of yesterday’s meeting. He wears his long hair in a topknot which is strange sight at first when you are used to the images of Gelugpa monks with their shaved head. Somehow I manage to understand and answer all the questions he asks me in Tibetan, which is a total coincidence: My vocabulary is not large and understanding the local dialect is not easy – I am probably much more surprised and impressed than he is!

Lama Namgyal invites me into his house, and although people generally have been very friendly I have seldom seen such hospitality. A young girl bringts me in the kitchen and after getting used to the darkness and smoke I see a large family sitting around an open stove and everybody inviting me to sit on the carpet next to the fire. It is crowded, half a dozen children, two women and the lama are having breakfast. They fill their cups with tsampa and soup from the pot. It smells tasty and I have not had breakfast yet, it is very tempting to accept their offers. But butter tea so early in the morning could be a shock for my organs of taste. The lama’s oldest daughter speaks good English though needless to say the vocabulary taught at school is not quite sufficient to answer a curious foreigner’s questions. Lama Namgyal has to laugh when I ask if the two women and a large number of kids are his family. No, he says, another family lives in the same complex and they share most of the rooms. He himself cannot live of being a lama, he owns a few fields and yaks are away for the summer.

The young Tulku from Shey seems to be the region’s pride. The lama talks him with some admiration. He has visited Shey thirty times so far, hearing that we just came that way and met the Tulku at Tsakhang pleases him.

Even though the house looks like a monastery from the outside it mainly serves a quarters for the families. A high wall is built around a forecourt, a small wooden door leads to the ground floor for storage where I have just had a brief face-to-face encounter with a calf, so it is also a small stable. Two stories higher is the kitchen, the centre of the house. Large pots and other utensils decorate the dark room, making it the most interesting and comfortable place of the house. Since the lama is busy taking care of a newborn baby he asks one of the older girls to show me the chapel. It serves a study room and is not very elaborate, but the adjacent assembly hall is well kept and contains many books and quite a few fine statues.

Such conversation make me realise how the people really live. Yet at the same time I see that their lives are so completely different that we will never really understand it, no matter how well we think to know other cultures.

Sunny rest days do have one big disadvantage: you feel obligated to take a bath in the cold river. I finally convince myself and am as clean as I was two weeks ago, at least that is how I feel. Saturdays seem to be kids’ bathing day also, it is a bit of relief to see that some are even less eager than I am and sit on the warm boulders watching the others enjoying the bath in the icy river. After cleaning myself it is time to do the laundry – clothes do not look much cleaner than before but at least they smell better.

Two small villages at the end of a little valley seem an interesting and easy to reach destination, on the way we pass another village that looks like a castle. Since all facades have the same colour and brush-wood is stacked on all the roofs it appears as one long wall surrounds the village. The blue sky and white clouds above the roofs make it a very impressive view. The valley looks similar to the main valley but on a smaller scale, it ends abruptly when it turns into a deep canyon one mile later. The terraces are emphasised more clearly because it is slightly steeper. Since the creek can irrigate not all the fields in the broad valley people have dug channels further up and divert water there. Water seems plentiful and there are only two villages, Ship Chok and Do-Ro, so it should be easy to distribute it fairly amongst all villagers. In Upper Dolpo where there is much less water every village has strict rules regarding water distribution and the fields. The villagers throw dice to determine who receives how much water, the one with the lowest number will come last. A big threat to the crops are goats and yaks, within a few minutes they can trample and eat a large area of vital grains. The owner of the field must then be compensated, the fine is a big cup of barley for each step in his fields.

Do-Ro is small, consisting only of 5 houses. One of them is a small temple, but the lama is not here. The steep canyon walls behind it are a contrast to the round hills on the other side of the creek, a similarly small village is situated there.

Ship Chok lies in front of round hills that resemble dunes across the rivulet. A red-coloured building must the monastery, supposedly fine paintings can be seen there. A large family is sitting outside, a woman is weaving and the rest of her family and other villagers sit around, chatting and drinking tea out of the Chinese Thermos. I have seen so many of those bottles that I bet it is the most successful Chinese export product. And old man gets up and shows us to his house, after another adventure on a notched trunk we are in the private chapel, a clean room with a few artefacts and masks. The views from the roof are great, especially over the wall of chortens down into the valley. Afterwards we visit the official gompa, the paintings in the anteroom must have been repainted, they are very simple and not as great as I hoped.

After getting back we enjoy a lazy afternoon with tea and cake. This treat makes it even harder to develop a real appetite for dinner, but once it gets chilly a spicy soup and hot food is greatly appreciated.

Do Tarap – before Charka La (Day 12)

After the rain during the night the wonderfully dark blue sky is astonishing. The sunshine makes everybody happy, but also a bit lazy. We rest more often and longer than usual, but since this is a short day it is not a problem.

The trail goes up to Do-Ro, once again the lama is away and we go on without visiting the gompa. The broad valley becomes narrow and splits into two smaller canyons shortly after the village. Soon after entering the southern gorge the trail disappears in a steep slope where a narrow footpath on the black slates requires attention. A wrong step sends rocks sliding down into the river. This is the worst trail so far, it is not used by many locals and only a handful trekking groups a year, therefore it is also not maintained. The most difficult part is over when we reach another fork half an hour later. Knee-high bushes with thorns slow us down a little but we steadily gain altitude. Several hawks pass us just a few meters away, make a turn far down in the valley and disappears behind the high ridge.

We could either camp just below the pass or cross it today. Since we are in no hurry and have enough time to reach Jomosom, we decide to stay on this side. If we went on we could spend an entire day in Charka, but the village is quite small and probably not too interesting. The pass just ahead of us looks much higher than 5’093 m, it might be the barren rock without any vegetation that makes it seem higher than it is according to the map. Landslides come down the very steep gravel hillsides quite often, to see if last year’s site is still there Khami walks ahead. He waves from higher up and we follow him, reaching today’s camp shortly before noon. Some clouds have built up during the morning, but the weather at the pass is still fine.

Who knows what the weather will be like tomorrow - I decide to walk to the pass today just for a glimpse of the scenery. Another foggy ‘pass-photo’ would be frustrating. Everybody thinks I am crazy, including Thomas, but he joins nevertheless. It is hard to guess how long it will take, because no tree or other object is there to help identify distances. I guess half an hour, but it takes almost twice that long and I am about to return halfway because I don’t seem to get any closer. But the thought of the fog on Numa La gets me motivated again. I reach a plateau and see neatly piled stones, but no mountains yet. Hopefully the real pass is not too much higher... five minutes later I stand on a plateau. The view blows me away.

Untainted stark wilderness, barren hills and high mountains lie beneath and in front of me. It is similar to Sela Munchung La, but now we are much closer to the range that separates Dolpo from Mustang. The only thing looking remotely ‘alive’ is a broad green valley straight ahead. A nearby black slate mountain with regular vertical stripes of snow on its flank looks strange. The big massif behind the Do Tarap valley is in clouds already, the peaks of Mukut Himal are also hiding. One of the two triangular summits to the east could be Dhaulagiri. After a few minutes I start descending because the wind is rather cold and I did not bring a jacket.

Walking on the stamped trail is slow, tiresome and hurts my knees. After two minutes I take a steep shortcut, running and jumping down the gravel slope Ten minutes later I am at the camp again where lunch is waiting. After this extra tour it tastes better than ever.

A really energetic hiker might walk to the nearby cave, explore the valley or climb one of the peaks, but I am ready for a rest and climbing one pass just for fun is enough of a noteworthy sidetrip for me. Dinner is exceptionally delicious tonight: potato soup, potato samosa and curry pulses.

It is one of the totally clear nights again when the stars shine so brightly that you think about sleeping outside but soon change your mind because it is freezing.

After Do – Keheng Khola (Day 13)

During my usual nightly excursion (too much tea) I find myself standing in thick fog which lets me see 5 meters, a few hours later it is as bright as fullmoon although the moon is only a small crescent. With great expectations I open the tent before 600, and I am not being disappointed. A cloudless sky, the sun just throwing its orange light on the glaciers and peaks of Norbu Kang – a perfect day.

After a hearty breakfast we climb the pass, taking the same way as yesterday. In spite of carrying my backpack I feel like flying to the pass and reach it with much less effort and also faster. The view is as stunning as yesterday, but the clearer weather makes it look lovely, whereas the day before the clouds gave the scenery a threatening impression. The high mountains of Mukut Himal rise behind the black slate wall. The evenly snowy peaks towards Mustang which I mistook for Dhaulagiri yesterday have no name (though one looks like Thorung Peak), the same goes for the broad summit which dominates the desert to the east. The peak is large and flat and covered by glaciers, reminding me of Kilimanjaro and the volcanic mountains in the Andes. Because it is such a strange sight for European eyes used to lusher scenery, it takes some time to find the endless hills and barren valleys beautiful.

Being the first on the pass gives me some time to build a small stone pile, by the time I am finished everybody else - except for the liaison officer - has arrived and starts constructing their own. Needless to say, my construction looks very clumsy compared to their elegant and quite artistic sculptures: Khami has built a high tower, Dawa constructed a modern-art house with slates. After a long time the officer finally arrives.

The descent is quick, once again the steep mountainside allows jumping down in the gravel. When the valley becomes flat we have more time to enjoy the walk and views. Ochre tones and gentle curves dominate the scenery. The landscape is fantastic, it is hard to believe that we walk in the area that looked so hostile from Sela Munchung La.

Further down the valley is a herd of yaks, the tents of the ‘yak-boys’ are at the foot of a steep hill. The three brown tents with the thick ropes look like spiders on the green meadow. The kids watch the cattle while the older people stay at home. Dawa went ahead and talks with an elderly man in front of his tent. He is the amchi, a Tibetan doctor, from Charkha and spends the summers with his wife and two other families in the pastures. He uses the season to collect rare herbs which are used for medicine. They stay at one place for a few weeks and then move on to other grazing grounds with their yaks and sheep. The yaks are rarely slaughtered. The sheep are sold wholesale in Jomosom, mainly for the Dasain festival, an important Hindu festival that requires the sacrifice of animals. The locals feel slightly guilty since killing – let alone sacrificing – animals is not welcomed. But they have to make a living and husbandry is one of the few ‘business opportunities’ (read: means for survival) up here where nothing else than grass grows.

The man is very famous for his cheese, he jokingly claims that people literally rip it out of his hands when he arrives in Jomosom. I try some of the fresh white balls which are laid out to dry in the sun. They taste like dry cottage cheese and are much better than the final product, dried cheese balls. I feel like chewing on a strange tasting pebble, it is definitely not one of highlights of the Tibetan kitchen.

To us this seems like an isolated place at the end of the world with little opportunities for its people. Yet the amchi’s son went to study in Dharamsala where he gained the Geshe degree. He is living in Kathmandu near Bodnath, and Dawa even trekked with him here some years ago when it was very difficult to find people who knew the area.

The couple invites me to have a look at their spacious tent. The most noticeable thing is the altar in the back, which is not as elaborate as in chapels but very nice. Seven bowls of water are placed under a row of pictures and several statues. The hearth is next to it, a teapot stands in the glowing fire, and herbs are laid out for drying. Bags with food are stashed in the corners next to rugs and blankets. No vegetables grow here, the main dish consists of tsampa which is ground with a small mortar that stands at the entrance.

The two other families have young children who watch us curiously but are very shy. A teenage boy leads a herd of 100 goats down the steep mountain, by the time they arrive everybody is ready: the sheep are separated and tied together. The women and children bring pots from the tents and start milking the animals, even the young kid who is barely five years old get a small cup and joins his sister.

The old man is asking for binoculars, but all we have are our cameras with zoom. He gets as excited as the kids who look through it, but focuses quickly on a snow-peak to the northeast. A local protector deity is said to live on its top and the amchi’s giggling and his exclamations make you believe he sees something that you don’t.

On our way up the small valley we pass half a dozen similar camps of herdsmen. Quarrels about land rights are rare and mostly arouse after too much Chang, they are not difficult to settle. Most of the people here are from Chharka, one of the two villages between the Barbung Khola and the Kali Gandaki. While the people in the Tarap valley have much land for agriculture, it is much more difficult here and the Chharka people depend on husbandry. Only thorny bushes grow on the hills which are sparsely covered by grass and flowers, and even this little vegetation can be found only near the river.

To my surprise we meet a large number of people. Many are on the way to the tents, the most forthcoming of our porters tries to persuade three girls to join us but after five minutes of laughing and flirting they go on. We set up the tents on a plateau in front of a low pass. The kids watching the cattle show more interest in us than they should, shortly before dusk they have to walk high up to find their sheep.

The colour of the sky changes from blue to black, slowly submerging the dark windswept clouds in the north. Soon afterwards the wind makes the temperatures drop fast. The joy of getting into the warm sleeping bag after washing and brushing your teeth in the cold is immense. It is also such simple things that make trekking so special.

|

Summary Part 4:

Miserable weather makes it hard to enjoy our crossing of Numa La, but we are rewarded by two fantastic days in the Tarap valley. The broad and fertile valley is quite a change and we enjoy the views over wide golden barley fields. The valley is densely populated (relatively speaking, of course), people are very hospitable and conversations interesting. Our rest day is spent lazing in the warm sun, for the next week promises to be tough. Soon after leaving the Tarap valley the fertile scenery gives way to a high desert. After crossing another pass we enter a hostile landscape. Only nomads from Charkha populate the area where they spend the summers on the pastures. We will reach their village tomorrow. |