MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

Unnamed peak on the way to the south base camp.

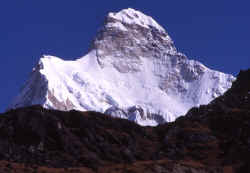

Another unnamed summit on the way to Selele La.

Tremaine standing on a ledge on the left, watching the

Sarphu mountain and the Nango La pass to the left.

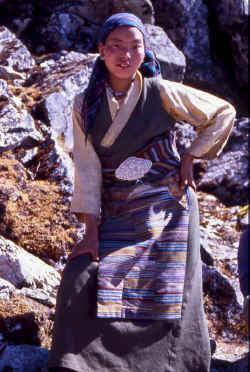

Women from the lower villages set up temporary lodges and

teahouses to accomodate trekkers and porters.

The top of Jannu rises above the ridgeline.

Porters on their way to Selele La meet the leftover snow that an unusual

storm dropped two weeks earlier. Luckily most it has melted since then.

The female porters carry slightly less, and act quite resolutely when the

teasing goes on their nerves.

A local women agreed to carry a load for a day and show us

the way - the friendliness and pride of the locals makes it very pleasant to spend time with

them.

Cragged and fluted ridgeline of Jannu's neighbours, many of them (officially)

unclimbed.

From the pass we even see Makalu and Everst. In the gully on the wooded

ridge we put up camp at Gyabla pass some days before.

Instead of going straight to Anda Phedi, we camp at Chachung lake.

Reflections of Kabru range in the Chachung lake.

From below camp the steep south-east ridge of Kangchenjunga rises to the

south summit. The main summit is the pyramid on the left.

Sunset on the mountains that form the border between Nepal and Sikkim.

Kabru range catching the last rays of the sun before the cool evening

arrives.

Memorable minutes before sunrise when the illuminated

clouds reflect in the Chachung lake, and the mountains are still silhouettes.

Rathong peak at the border to Sikkim is a fine pyramid of

ice and snow.

Kabru looks like a wall from Anda Phedi when the sunsets sets it abruptly

against the forested valley.

Kangchenjunga Olung: Ghunsa - Mirgin La - Anda Phedi

Ghunsa - Mirgin La - Anda Phedi

Kambachen Ė Ghunsa (Day 22)

Judging by the icicles in the tent, it was a cold night. I wake up early and canít get back to sleep, so I wait for the crew to wake up and the sun hit the tent. I finally get up and try to dry the clothes which have been wet for the last few days. After breakfast I stroll around the village for some minutes, but most houses are locked. Those locals which are still here are preparing to lock up for the winter and go down to Ghunsa and Gyabla. The fields are not looked after, I wonder if thatís because potatoes are grown and not much care is required.

I havenít been feeling well since I woke up, and by the time the first porters from the other group arrive from Lhonak, I feel stomach sick. I also feel the apathy that accompanies nausea. Iím not a very social person in that condition and instead of waiting for the group to arrive I go for a walk up the hill above the village. I refrain from eating for another day, and the uneasy feeling eventually disappears in the afternoon. Prayerflags mark the top of the hill. The views to the north bare the wide bed of a melted glacier. A huge white flat mountain forms the horizon. The long plateau could be part of Jongsong peak. In the southwest rise the spiky fluted peaks of Sarphu range. Despite being covered behind a hill, the most dominating feature is Jannu. Just the very top is visible, its red rock face is intimidating. The snow on the southwestenr ridge is a perfect dome, modeled evenly by wind from both sides.

Small dots move down from Lhonak, and when the slightly smaller dots (tourists without loads) arrive, I walk back down to Kambachen. My group arrived, after not seeing each other for a week and realize that it is nice to be around other trekkers, but that I donít miss them when Iím alone. Some people seem to be doing things and need to share them in order to really appreciate them. Iím content to enjoy it myself (though I do appreciate comments on my diaries and pictures on the web). Their journey from Olung to Lhonak worked out as planned. The only mishap was that the yak driver did not unload the yaks at a narrow spot along the river, and half the herd plunged into the water. One got seriously injured, and had to be killed. At Lhonak the amount of snow prevented them from reaching the hidden glacier. Instead they opted for a walk to Pangpema with great views of Kangchjungaís north face, and they got even better views when climbing a 6í000 m above the base camp.

The amount of snow in the Khumbukarna side valley is also rather discouraging. On the slopeís the snow has not melted yet, and higher up on Mera it could turn out to be critical. Instead of wasting more time on the north side, the majority wants to try the south side and maybe have an attempt at Bokton.

There are two options for me, either go the same way from Ghunsa to Suketar or stay with the group for some more days and take the route via Sinion La and Mirgin La. Iím undecided.

I leave out lunch, afterwards clouds move in and we start for Ghunsa. Jannu and to a lesser extend its tributaries seem to play with the clouds Ė once hiding and then defying them Ė the drifts of clouds just make them mightier. The sun shines for the rest of the day, but gets dimmed by clouds occasionally and the temperatures drop quickly. An icy cold wind blows near the moraine, but subsides further down. I try to get to Ghunsa quickly, and donít appreciate the scenery as much as I should, but in my defense I can say that Iíve walked that trail three times already. Most of the way down I imagine butter tea, potatoes and the comfort of a living room with a fire. Thatís exactly what is happening in Ghunsa in the afternoon. Fog makes it colder than usual, and we all get rooms inside the lodge instead of staying in the tent.

Ghunsa Ė Sele La (Day 23)

The cold makes the first few steps very clumsy, and the intangible sun that shines on the surrounding hills already just makes it seem even colder.

Last night I decided to walk out via the south route, and not the direct way. Ang Dami and two porters will join me. The others will walk towards Kangchenjunga south base camp, but I have to be back in Kathmandu one week earlier and wonít be able to join them. Again Iím grateful to Jamie, this flexibility is great.

On the way out of the village we pass the burned-down police station and the deserted school. After a short climb weíre on a ridge where the sun hits. After undressing we cross a small river and cross a wide grazing area where the porters have stopped for an early lunch. Then we head up in the forest, mainly rhododendrons grow in the intact forest where there is no trace of logging. The climb is quite steep and strenuous at first, and then gets gentler when it follows the ridge. Moss covers everything, thus reducing all sounds. The occasional fall of a leave seems very loud. I spot a few little black mice, not because I see them but thanks to the noise they make when running through the dead leaves. The atmosphere is incredible, and the light green of moss everywhere puts a green hazy layer of the scenery. The clinking sound of my walking sticks feels very intrusive and I stop using them.

When the forest gets more open, the fresh wind and sound of birds announce a different, less dreamy landscape: weíre above the forest and on the edge of the ridge. A little further ahead are prayerflags. The views from the boulders are spectacular. Far below, like from an eagle perspective, lies Pholey, up the valley are two fine peaks east of Jannu, to the right lies the range we will cross the next two days. I feel more out of breath than I should after three weeks of hiking, but Iím not concerned and enjoy the scenery.

The trail traverses the hillside whose dry yellow grass contrasts nicely with the blue sky and the dark rocks. Two creeks cut across the path, at the first one a bird hops away when I get within five feet, but lets me follow him for some time. After the second creek the trail climbs steeply up in a little gully, a hundred meter higher is the pass. To the right a dark rock peak leans out into the valley. Instead of going straight to the pass I climb up the decently wide saddle. The views are stunning; the Ghunsa Khola runs in endless cascades towards the low land where the hills follow each other and disappear in the haze. Across are the two passes to the Olungchungkola valley Ė Nango La is the higher one to the right, further left just above Gyabla is the one we took.

On the pass I meet a mother and her two daughters who carry loads. Iím wondering where they are going; the trail runs through a field of dark boulders and ends in a ďclearingĒ. A little stream meanders through the rock-free circle. After three solitary weeks Iím not prepared for the scene: three groups have put up camp and locals set up little shops. The locals come up during the tourist season from Ghunsa, and set up little teashops and shacks for kitchen crew. Most of our porters are from the same village, and to their surprise they meet the other half of the village up here. Theyíre also working as porters. Their reunion is celebrated, and I must admit Iím proud that we seem have the better half of the village: no gambling, smoking or drinking.

Their party does not last very long, or maybe Iím just too tired to realize.

Sele La Ė Mirgin La - Chachung Pokhari (Day 24)

The sun hits early and in nice temperatures we slowly gain altitude. Patches of snow become more frequent the higher we get, at the foot of the next pass they turn into a single snow field but the trail is free of snow. Most of the porters have put on their sunglasses, even the girls you usually donít like them at all. Despite the winterly surroundings and the altitude, itís hotter than the days before. The scenery is magnificent even before reaching the pass: the mountains of Yangma rise in the distance, just behind the barren ridge towers the upper part of Jannu. Itís an easy walk and after a short final climb weíre on Mirgin La, roughly 4í500 m high.

Itís hard to get moving again once you see the views: 60 km in the west rises Makalu, despite the big distance it is ridiculously high and huge. Clouds start to gather on the summit to its right: Mount Everest. The closest mountain is Jannu, for the first time the south-east face is not blocked by other mountains and the lower part is just as impressive as the top: a seemingly unclimbable buttress that is guarded by knife-edged ridges further down.

Weíve taken it easy to the pass, and remain there for almost an hour. Iím happy that pack-lunch is cancelled and that the kitchen crew has gone ahead and prepared lunch on a little plateau. The weather is brilliant, dal baht with views of Makalu - I couldnít wish for anything more. If I had any doubts about taking the long route, they have disappeared during the last two hours.

After lunch we traverse to an unnamed third pass, on whose other side we cross another gully that is free of snow but towards Sinelapche Bhanjyang (4í640 m) the snow rises again. Crossing two weeks earlier must have been a nightmare. The trail branches shortly after the pass, to the right it drops and goes directly to Anda Phedi. We continue straight and traverse black rock faces. For an hour only the fogged in peaks of the low Singali range distract the eye. Then, when the trail bends to the north all of a sudden another spectacular view opens up: the eye starts far down in the Yalung glacier and slowly wanders up, first to the symmetrical pyramid of Rathong, then the long ridge of the Kabru range with its four peaks of 7í300 m. To the left of it, a long steep ridge leads to a reddish rock face with three summits that sit on top: Kangchenjunga.

I wait for a long time at another unnamed pass that is marked by prayerflags and a lhatso. Iím completely stunned by the views. Most people will not have a chance to see the beauty in their lifetime that Iíve experienced in just the last three hours.

Straight below is a little green lake, the path goes down steeply and requires some care. According to the map this canít be the campsite. Luckily the map is wrong and we really do stay at this lovely spot: grass grows around the lake, the mountains reflect in the smooth surface of the cold water. A long time after us the porters arrive in small groups. We set up the tents along the shore, when the sun disappears behind the hill it gets chilly and the tent is the coziest place. The colors change as the sun is setting. At first the foreground is getting darker while the Kabru range has a perfect white. Then the snow changes to a yellow first, and soon afterwards glows in orange. This strongest color only lasts for a few minutes and is followed by the last tone of pinks before it also fades and the mountains retreat into darkness.

After Olungchungkola I get my second good-bye dinner: dal baht. My appreciation is further increased because it was organized by Nicola who does not like lentils at all. For dessert we get a cake with a note: ďcome back for next trekĒ. I will.

Trekking with this group was really enjoyable; everybody was nice and had the right mix between group-consciousness and independence. After watching the stars for some minutes, I crawl into my warm sleeping bag and doze off replaying the stunning scenes of today.

Chachung Pokhari Ė Anda Phedi (Day 25)

I wake up before sunrise and luckily get up instead of going back to sleep. Itís been a cloudy night, and I witness a fascinating sunrise: the sky has a very intense light blue color. The rising sun illuminates the clouds from below and turns them into a bright orange and yellow, the upper parts of them are dark gray. The mountains are black silhouettes, only the lake takes is an orange oval in the darkness. Clouds are drifting from the south to the northeast, blocking the sun from reaching the Kabru range. For some moments the east face of Rathong and the peaks of Kabru get the orange ray of the sun, then clouds prevent any further play of colors.

After I get back from a short walk the porters who slept under a big rock are warming up in the sun. Our group will split today, Iím going down to Suketar while the others head north for Bokton peak. Therefore packing takes a bit longer, but since both of us will have a short day it doesnít matter. Logistics for treks are not easy, and if it seems simple it is only because the sirdar has everything under control: who goes where with which loads, what can temporarily be left behind and estimating reserves are not an easy job.

I get some instructions from Jamie to prepare their return in a week, medical advice for Ang Dami whoís cut his finger the day before. We descend steeply and lose several hundred feet in little more than twenty minutes. Near a little plateau the trails splits. I take one final group picture with us tourists, Tenba (sirdar), Ang Dami and Gyurmen. I hoped Mangal would accompany us, he was shy in the beginning but has opened up and weíve had some talks in basic English. His serious face and dark eyes often light up and display a warm smile. Instead of him Lama will carry the loads, the strongest porter who is often walking far ahead on his own. Ang Dami is a very helpful and nice guy, though his English isnít that good it didnít prevent us (or me at least) from having a pleasant time in Yangma. And since he is also a very good cook, Iím very happy to have him for the rest of the trek. His wife is pregnant and heíll go straight from Suketar to his village. Gyurmen has had a bad throat and will also carry a load down. Even though he was very attentive and helpful during the entire trek Iíve never felt very comfortable with him. Iím not sure if heís friendly just for the sake of it or if he expects something in return. Ttwo months later I got a mail from him asking about money or getting to the west. My skepticism was right, but in a way itís understandable because there is a lack of opportunity and I donít blame him.

Rathongís southwest ridge rises in a straight line to the summit, further south are the side valleys that would take me directly to Sikkim. I wish itíd be possible to cross there, but only Indian expeditions get the permit to get in and out of Sikkim via the mountain passes, and even for them it's not easy. The early explorers faced a different problem: getting into Nepal was almost impossible, and Sikkim was open.

Another half hour later weíve reached the bottom of the valley, and the settlement of Tseram. Two houses were built for trekking groups who stay here before going up where weíve come from. Kangchenjunga is in clouds, but the range in front build an attractive horizon, dark green junipers and red bushes grows between the dry grazing area where some young yaks wander. We stop for an early lunch, I havenít burned many calories so far but the crew needs energy to carry the heavy loads to Anda Phedi. The trail follows the river, a small area between the river and the steep barren rock face is covered by forest, the left river shore climbs more gently. Firs at the bottom, rhododendrons on the higher slopes which make way to small bushes and at last snowfields. A warm wind from the south blows the lichen like prayerflags, and brings a strong smell of wood into the glacial valley. Weíre walking downhill gently, the snow on the mountains decreases and after not even two hours a single house appears in a clearing: Anda Phedi. It is locked, but from higher up the sound of an ax indicates that the owner has not locked up his lodge yet. We ask for potatoes, green vegetables and clean water. Whether itís the lack of food or the fact that itís still early, there is indecision: should we stay or go on. I donít mind an early stop since itís warm, finally the prospect of spending some hours on the river convinces me to stay, and we stick to the original itinerary.

I go for a wash in the river, a refreshing one but on the hot rocks itís relaxing to dry in the warm wind. When cold breezes start, it gets cold. Laying on the mattress outside the tent for an hour dozing is another highlight. The sun is setting but for once the temperatures donít drop suddenly to freezing point. The valley is in the dark already, but behind the fine silhouettes of fir trees the gigantic wall of Kabru glows in an orange light. Within minutes the hillsides turn blue, gray and black and the snow from yellow to orange to pink and finally into a strange white.

Ang Damiís soup is ready when I come back; due to lack of supplements (Papadum and popcorn went north with the group) he made a very tasty snack out of dough and fried the finger-sized pieces in oil. Iím really moved by his care. After dal baht I watch the brilliant colors in the sky for a while and enjoy the warm temperatures. To the south the hills are silhouettes against a dark blue sky, only the ridges are orange. Hopefully tomorrow evening will be as nice as today, weíre likely to camp on top of a hill tomorrow.

Anda Phedi Ė Lasiya Bhanjyang (Day 26)

A late start when the sun hits our side of the valley makes is easy to start. Clouds are gathering in front of Kangchenjungaís south face already, blocking views of the summit. The colors in the valley are stunning; the moss is a bright green, the sky pure blue, the clouds white and the silhouettes of the forest black. Itís a nice walk, though often the trails are slippery and muddy. The fir trees give way to rhododendrons; somehow I get the impression that there was more variety of trees in the other valleys. Little creeks from higher up flow into the Simbuwa Khola whose bed becomes more narrow and forces the water to rush down steeply in channels. At Tortong we cross over a bridge and continue on the side that still lies in the shade, nevertheless it is quite hot already. The heat and humidity slows all of us down. At the foot of a large ascent we stop for lunch at a creek, the one for the next two hours. Dark green junipers and yellow maple leaves contrast nicely against the blue sky, I watch them dancing in the wind and relax.

The afternoon is strenuous, we all sweat more than on any other day. The constant climb is not very steep but continues for a long time. A huge landslide interrupts the green of the hills like a gray scar. The constant trickling of falling rocks and sand follows us as we cross Ė most of the sound is caused by ourselves, but thereís also the discomforting sound that comes from higher up. There are some narrow spots, and a gap needs to be crossed on two round wooden trunks.

As we get higher, fog drifts from one side of the valley to the other, I assume weíre close to camp (Bhanjyang means Ďsaddleí in Nepali). Then weíre out of the landslide and on a fifteen feet wide ridge, though itís not visible Ė too much fog - one can feel it. The landslide starts at the ridge itself. For some moments it clears and Jannu Ė once again Ė dominates the view but it reaches higher into the sky than before. When fog moves in itís most picturesque because the whole valley is filled, only the nearby trees and the very top of Jannu escape the gray veil. We set up camp on a little clearing, an open shack that serves as goat stable in summer is turned into the kitchen. Before dinner I set out to climb up the hill to the north. The trail slowly disappears in the undergrowth; I fight my way up for another half hour in hope of reaching the top and finding a spot that letís me see the mountains in the north. Eventually I turn around; Iíd probably have to climb a tree because the vegetation is too dense to see anything. Instead of straight going back to camp I stick to the right and climb up the hill above the camp. I should have tried that spot in the first place, but Iím lucky to see the fog dissolve for a moment and the snow on top of Jannu reflects the orange evening light.

Back at camp I see a bad example of Nepali culture: as soon as got there Lama started a fire, nearby was a pile of dry bamboo and he added that and threw a big trunk on top. Bamboo burns instantly, gives high flames and a loud crackling sound but this last only a minute and then itís all gone. Instead of collecting twigs and bigger branches which are lying in the forest to make the fire last, they continued to put bamboo on top. Now all the bamboo piles are gone, itís dark and cold and they huddle around the remains of the fire and are cold. ďKe garneĒ is a famous Nepali saying, that can be translated as ďwhat can you do?ď In moments like those I believe those two words to be Nepalís philosophy. And maybe thatís the only way to stay sane in a country ruled for decades by corrupt, ignorant and incompetent leaders. This slightly fatalistic approach certainly has its good sides, but sometimes I feel that it also hinders activities. Not that other nations would have done better at the fire: Germans would have just taken logs from the large stack 20 meters away. Swiss would have collected the nicest firewood you can imagine and after a long discussion decided that it wasnít really that cold to justify burning the wood yet.

|

Summary Part 6:

From Ghunsa we traverse over low passes to the southern side of Kangchenjunga. On the way to the first pass, Selele La, we walk between yellow grass and enjoy the views of stunning mountains and the valleys below. The Mirgin La is covered by some snow, the views of Jannu are simply breathtaking. Knife-edged ridges protect the main summit that rises steeply above everything else. On the horizon we see Makalu and Everest. The camp at Chachung Pokhari is simply perfect. The mighty Kabru range reflects in the still water of the pond. At sunset the sun turns the snow into an orange colour before the peaks retreat into darkness. The others have another week and head north, I return to Kathmandu with Ang Dami and two porters. The sudden vegetation and smell of herbs make the walk down very pleasant, and the warm nights are another welcome indication of reaching lower altitude. We climb another pass, Lasiya Bhanyjang, where fog drifts over the steep ridge. Occasionally, the silhouettes of trees appear out of the mist and Jannu towers mightily above the eerie scene. |