MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

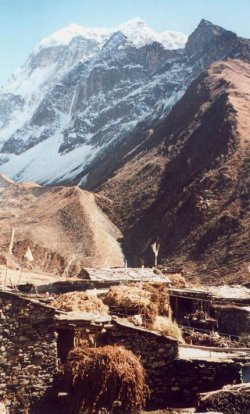

Samdo is a lovely village of two dozen simple Tibetan houses was founded by

refugees just 50 years ago. It is situated at the confluence of three valleys

and lies in the shade of Pang Puche.

Barley corns being roasted and then ground into tsampa.

After performing a protection ceremony in the house of a wealthy family, the

lama and laymen carry the effegies and offerings to the town's chorten.

Kids playing around their house.

There is little land for agriculture, the men are away during most of the summer

and autumn with their yaks. The border is just a few hours away and the passes

just a little more than 5'000 meters, but trade volumes are decreasing.

The small dots at the bottom of the valley are the houses of Samdo, as seen on

the way to the base camp for Larkya La.

From Dharamsala it is a three-hour walk along the moraine to the pass. Its

official height is 5'220 meters, supposedly it less than that.

The view to the east with Pang Puche.

Larkya La: View to the west. After walking down the steep trail above the

moraines for a few minutes, the Annapurna range rises beyond Kichke massiv.

Between the three moraines in the valley lies a turquose glacial lake.

Resting on the pass and enjoying the magnificent surroundings!

Larkya La: View to the north. Cheo Himal forms an impassible barrier to the

Tibetan high plateau.

Manaslu: Sama - Larkya La - Bimthang

Samdo - Larkya La - Bimthang

Sama - Samdo (Day 15)

I feel much better but still weak, hopefully just because I have not eaten for a day and not because of something else. I skip breakfast assuming to make it easily to Samdo, since it should be a short day.

I want to catch up at least a little on what I missed yesterday and have the luck that some people are at the monastery. Laymen and monks sit around the fire in the closeby building and assure me that is ok to enter. The smaller chapel on the left seems to be the library, many books with beautiful silk covers are in large racks, wrathful deities are depicted with fine paintings on the walls. The altar on the larger room contains statues of Padmasambhava, other historical figures and a large red-painted Vajrapani in the corner. The bronze statue of Guru Rinpoche was manufactured by Patan craftsman about 100 years ago. The painted wooden panels are very beautiful, the rural paintings are equal masterpieces of art. Looking at everything would take hours, so no matter how much time I spend in these rooms it will feel like 'rushing' through it without giving the attention they deserve. An old monk sees me leaving and waves me to look at another chapel, I am not sure if the small chapel is his private room or part of the complex, unfortunately the thangkas show their age.

It is a fine view from the monastery and its colorful prayerflags down to the flat valley and mountains rising steeply above it. The wide valley is becoming narrower as we climb higher, below the glacier we get the most stunning view of Manaslu. I can already see myself sorting out pictures at home, trying to find the best one of the mountain. We pass a long mani wall with fine carvings, afterwards it gets a little steeper and I slow down - probably due to skipped meals and not altitude. I really hope that the feeling in my stomach indicates only hunger, but I am too afraid to test it yet and try to not to eat anything today. Now we walk parallel to the Buri Gandaki again. After crossing it on a wooden bridge it is a steep climb up to a simple chorten, a few minutes further up stands a more elaborate whitewashed chorten. One valley goes north, another one branches off to the west. Trails follow both valleys but no village is in sight and I start worrying since I am running out of energy.

When I get to the chorten I am surprised to see three houses just ahead of me and a few seconds later a whole village on the valley to the east. This is Samdo! I have a whole afternoon for exploring and resting. The simple houses stand at the junction of three valleys ('sum' means 'three' in Tibetan and probably led to the name), Pang Puche (6'338 m) towers above it. Its moraine forms the eastern valley, the one to the west comes from Manaslu and a river flows in the northern valley that goes almost straight to Tibet. Most of the fields lie on a triangular plain between the two last valleys, some are just in front of the village but agriculture cannot play an important part in people's lives. There is simply not enough fields to live on, therefore trading is probably more important. The village was established in the 1950s by Tibetans who fled from Chinese occupation and moved into Nepali territory.

This is one of the places I enjoy most when trekking - isolated and surrounded by barren hills, with friendly people who do not mind a curious but reserved tourist exploring their village. Two whitewashed buildings stand out amidst the two dozen houses, one holds a large prayerwheel, the larger building is the monastery. The main door is locked and the caretaker nowhere around. The sound of drums and wind instruments comes from a house below the gompa, since many of the reasons for holding a private ceremony are not pleasant I do not want to intrude and watch the 'simple' village life instead. This includes joking around with local beauties - something I would not do in the Hindu villages because it would feel too weird, but here the girls are very outspoken, self-assured and down-to-earth. Their dresses are simple but very effective, under a short-sleeved dark colored chuba they wear fine silk blouses. Attached to the woolen waistbelt is a silver spoon with a turquoise, its meaning is unclear but they are proud to point out that it is becoming a fashion in other places, too. The necklaces of turquoise and red corals, the golden earrings go well with the dress and the colorful strings in the braided black hair. I usually never ask twice when somebody does not want to be photographed, but after - honestly meant - compliments the shyness often disappears. I promise to send copies, Bharat comes here often and can deliver the pictures since postal service to remote areas is unreliable at best.

Most of the men are away on trade, the older kids are watching the cattle on the meadows and return just after dusk. Nevertheless, the village is full of activities: weaving, flailing, cooking, baby-sitting, gossiping, etc. A woman waves me into her house where she is making tsampa. A small door leads into a dark room where a juniper fire serves at the hearth. In a large pan barleycorns are mixed with fine black sand and then roasted over the open flame. For some reason, barley has to be roasted before it can be eaten. The sand prevents burning and makes the corn pop a little. It is then shaken off and the corn is grounded into a fine flower. Mixed with water and siben (chilli sauce) is tastes ok, the original version with butter tea tastes a little strange to most Western people. Chimneys do not exists out of fear that a demon could enter the building - whoever invents a solution that does not contradict local beliefs will be a preventer of many eye-diseases.

It is easy to romanticize the lives of these people. To a Westerner it seems simple and fulfilling at first. And really, despite the hardships of everyday life many people are happy and satisfied - at least that is the impression I got. But basic things like decent healthcare and good education are absent in the villages, and people rightly feel that they do miss out on some very valuable things that would make a huge difference in their lives. And that is all what they are asking for, not roads and TVs, but healthcare and schools. The government simply cannot provide it - I am not to judge whether that is because it is of financial and logistical problems, or because of corruption, or because of something else. But to those people it must seem like nobody in Kathmandu gives a damn about their problems.

Decentralization and the creation of Village Development Committees are a step into the right direction. However, as long as they do not get more resources (this includes not only money but also political authority) to organize themselves, nothing will really change. The success of the Maoists would not have been possible without the support or at least acceptance of the local people. I do not know if the Maoists really run things better than the government on a local level, and I doubt they have the ability to govern the whole country effectively - but it will be hard to do a worse job than the current government. With all the changes of governments, Prime Ministers and unstable coalitions, not much can get done.

Somehow I feel that Nepal is facing very difficult times. When I came here the first time 10 years ago many people were excited about their future when they thought about the possibilities of democracy. These hopes seem gone in many places, it is not that people are showing their anger and disappointment openly, but they do not anticipate changes for the better anymore. The following editorial in a newspaper sums it up very well:

"The education sector is in very bad frame. The economy is in a state of rupture. The law and order synopsis is clear to us all. The social sector remains divided on partisan lines. Nation's academia most unfortunately stands in a clutter. The bureaucracy is sinister to the extent that with the rumor of a possible change in government or party leadership, they keep their pens down thus hitting the nation very hard. The leadership in the government apparently feels that while being in government they should amass wealth for generations and generations to come with the possible fear whether next time the voters will prefer them or not. The coterie in and around the ministers and the Prime Minister is also talked to be highly corrupt. The very core parliamentary organs, which have been allowed by the constitution to issue strict directives to the government for do's and don'ts, have either been neglected or thrown to the waste basket summarily." - Telegraph, 6 December 2000

In the last few years, 1'500 people died in the conflicts. The influence of Maoists has been growing, it is doubtful that it will decrease despite the formation of special courts and the creation of new armed government units to fight the 'insurgents'. Before I came to Nepal this year I was in favor of the army getting involved, now I realize that the underlying problem that gave rise to the Maoists is poverty and missing development - and these challenges will not be solved by military force.

[Important note: I am not a sociologist living in Nepal, only an interested tourist who tries to follow Nepali politics also from back home.]

As I pass a large house, an older woman invites me to come in. A large family sits around the fire in the spacious living room. Then I hear the drums and recitations again, this time much louder since it comes from the adjacent room. After some seconds the eyes get used to the dark and I see a small door leading to a private chapel. It is a room 3 to 5 meters wide with some dozen books, statues and thangkas, not lavishly decorated or furnished, but obviously in regular use. Four monks sit opposite each other and recite texts with an occasional glimpse at the scripts. Three of them seem to be laypeople, only the youngest, a man of about 30 years, is wearing monk's robes and a red hat. He is the lama and knows which scripts are next. The others recite the texts and play the instruments.

The ceremony is performed to ask for protection. A simple looking effigy made out of tsampa is placed on a plate with barley. It seems to be the center of the ceremony, a much more detailed figure, a wrathful black painted protector deity with the head of a bull (Yamantaka?), has so far been placed in the middle of the room without getting any attention. Suddenly the lama takes the small effigy and throws it towards the door. At that point I decide to leave because I feel I might be disturbing from now on. The small procession of monks and curious kids is walking to a small chorten at the town's end, carrying with them the tsampa figure, Yamantaka, a bucket with burning horse dung and juniper branches, while playing the instruments. There more texts are recited, though it is hard to tell from the distance what is happening exactly.

The procession is followed by the same French tourists who just half an hour ago gave a demonstration of their cultural awareness by handing out pens to begging children. Maybe it is prejudice or the fact that many groups from France come to Nepal, but I have often witnessed French's utterly disrespect for local culture. It just makes me sick and also embarrassed. And the only word that the 'Grande Nation' seems to be able to mutter is 'bonjour'. Their liaison officer left at Jagat, but even if he were still with them he probably would not have interfered. Manjul, our liaison officer, promise he will talk to them (they would not want 'us Americans' to criticize them), though it is doubtful that he will. He never complained when we or our crew went against the regulations. And even if he mentions anything in his report, nothing will happen.

Some of us climb up the valley towards the border, hoping to get a glimpse of the vastness of the Tibetan high plateau. They cannot quite make it to the pass and did not think about taking tents and some food, but they did get fine views and do not regret the sidetrip. I am not up to strenuous exercise yet, and also skip an easier sidetrip up the hill just above the village from where the views are probably awesome.

I take a nap on a haystack on a roof instead, just one of the many pleasant experiences when trekking. It is a pity that I was sick on the days with much time for longer excursions, but I feel lucky not to have become seriously sick. And spending time in such villages is at least as rewarding as great views. I regained some strength thanks to the electrolyte that tasted sickening (in the true sense of the word), but with a sip of Tang in between it was endurable. It surely helped me to walk up the hill this morning. My stomach can handle snacks again, hopefully I will be on 'normal' portions (which means double or triple portions) back soon for the pass.

The sun disappears very early behind a hill, and it gets cold just after 300. Bharat and Tenzing call me to join them in one of the shops. It is a very comfortable place with a carpet around a fire that is not too smoky. The 'aja la' is a 30-year old Tibetan whose husband is coming back from Tibet in a few days. She is flirting more than I really like, and receives much support from Bharat. She suggests marrying (after assuring me that she has no children) and taking her to Switzerland. The offer is not too serious, but to be on the safe side I point out all the negative things of Western society in hope of destroying the fairy-tale image.

While walking around earlier I met the teacher of the local school, a man from the low lands whom I did not like at all. Now the slimeball is joining us in the shop, after a five-minute conversation I just have to leave. Then I meet the lama, who invites me again into the chapel. The main ceremony seems over and the atmosphere is more relaxed. The final part seems to consist of three recitations, I wonder if the hats have any significance. He is not wearing one during the first prayer, for the second one he puts on a yellow cotton cap, then a red hat. The community follows both the Nyingma and Kagyü tradition (he even calls the monastery Nyingma-Kagyü), so the yellow cap cannot have anything to do with the Gelug tradition. I am given butter tea and there is no way I can decline, though I am very worried about my stomach. I take a few sips, smile to people, and when nobody is watching pour it between the wooden planks on the floor. This is terribly rude, but once you spent a night at -10° C in a tent worrying about throwing up every time you woke up, you will understand. Though I must say that so far I never ever got sick from local drinks, be it rakshi, chang or butter tea.

The family's eldest member is an old, old man. With great pride he was cleaning an ancient gun for most of the afternoon, and now he straps it to the other weapons that are tied to the pillar in the chapel. So my impression that - despite the missing statues of dharmapalas - this is the gonkhang (room of protector deities) cannot be entirely wrong. Chang is also served, and one of the drum players is now holding a baby in his arm. The serious religious part of the ceremony is over. It was sponsored by the wealthiest local family. Monsoon is over and the difficult wintertime begins. The ceremony was performed to protect the village, its inhabitants and the animals. The village's dzos (mixture of cow and yak) are brought to Manang in the coming days. They have to spend the winter in lower pastures since they cannot deal with extreme cold. Most of the yaks will be in Tibet during that time, because snow on the south side of the Himalayas makes fodder difficult to find.

Despite of being in the same village committee as Sama, the people from Samdo are not allowed to trade wood. Therefore they have specialized in trading jewelry, and of course when you ask them business is very bad, so it is difficult to tell how well they are doing. I cannot imagine them to be very wealthy, because some of them came here recently, but supposedly some are affluent enough to own houses in Kathmandu and Pokhara.

This was a great day: in the morning I was worrying about my health and half a day later my mind is filled with all the interesting scenes from the village.

Tomorrow we will walk towards the great white peak that is rising above the brown barren hills in the west. Larkya La must be somewhere close to it, and because the walk to base camp is short I can probably spend another day in Samdo.

Samdo - Dharamsala (Day 16)

As usual, the sky makes the toilet stops at night an (almost) pleasant experience. Apart from that, I sleep much better than yesterday and regain some strength. And I have only one strange dream: "The first thing I did when I got back to Switzerland was signing up for Cho Oyo climb - and being scolded by my mother for it." I hope this is a good omen for Chulu Far East.

I get to experience another wonderful sunrise, this time over Himal Chuli. We pack early to make it easier for the porters, they like to start early to escape the freezing temperatures and the hot sun in the afternoon. Though it is freezing before the sun hits the camp, it is much warmer than in Sama. Dharamsala is probably not very exciting, so I stay in the village for as long as it is interesting.

Our red hand-washing bucket was stolen last night, which probably makes us look even more primitive in the eyes of the French. Remember, our toilet tent was stolen a week ago and the hand-made alternative does not look very fancy. Now everybody makes jokes about the French. I think at first people thought that my dislike was just prejudice. Well, I really was prejudiced but it all turned out to be true.

A yak caravan arrived yesterday night, they started packing an hour ago but are still busy when we finish breakfast. It takes a long time to get the yaks ready and loaded. It is a great scene, if the pictures turn out half as good as the ones I have in my mind I'll be very happy. Just the colors by itself are wonderful; the white, black and brown yaks, the men with woolen caps and white shirts, blue sky, ochre hills and the white summit on the horizon.

Afterwards I stroll through the village for a some time, and see that the door of the gompa is now open. I meet the lama and the 'laymonks' again, they are preparing more tormas. The head lama is forming square pedestals out of tsampa and glues them together with a mixture of chang and barleycorns. The iconography is clearly laid down and he consults the detailed instructions for each of the figures. His 'colleagues' prepare other parts of the 'mini-chorten', later the figures are put together, painted and finer figures made out of colored butter are added to it. Simple tormas take about three hours, there is virtually no time limit for the larger and more elaborate ones. Ironically, the lama did not get any of the pens that the French handed out yesterday, though he is probably the one who really needs them for drawing the instructions.

The sleazy teacher has noticed that I do not like him very much, some of the locals don't seem to like the school very much either. On the one hand I can understand that teachers from the low land do not like to be in such remote areas. It is cold, the food is different, the culture is unfamiliar, the salary not very enticing either. But they are teachers and should try their best. A good teacher can make a huge difference in these kids' lives. In Lho two government is paying for two teachers and a doctor at the healthpost - all three simply never showed up. At least the VDCs are getting more money and can employ their own teachers now. Of course it is best when a teacher returns to his own village after finishing education in Kathmandu, but it is must be hard after enjoying city life. Educating children often raises awareness of their parents, and thus the development of a whole village can increase dramatically by having good teachers at the local school. Maybe there would be more teachers if women's education were to be encouraged, I have never met a female teacher in remote areas.

I decline the offer of tea, and also the one of rakshi and chang, and when I tell them that I also do not eat meat they jokingly say 'kyerang lama ray' (you are a lama), my reply 'lama detsi yin, yineh phö pumo peh nyingchenmo dug' is causing much amusement. Encounters like these are worth climbing many, many hills and passes... But my language skills still need much, much improvement, luckily Jamie is also here and can translate his conversation in Nepali.

After passing the fields and climbing slowly up towards Dharamsala the village becomes smaller and smaller. I often turn around and remember the pleasant time in the houses that look microscopic now compared to the huge Pang Puchi next to them. The trail runs above a moraine from the hidden Manaslu massif, above it rise rocks walls too steep to be covered by large snowfields, 'only' the ridges and summits are white. Red bushes, mani walls and chortens make the scenery more stunning. More and more peaks appear as we higher up, at first Larkya Peak is most impressive, then the two peaks of Manaslu take over.

The scenery has been fascinating the whole morning, huge mountains to the left, 'small' barren hills to the right. The campsite offers equally stunning views. It takes about three hours from Samdo, the short walk that leaves plenty of time for acclimatization and 'lounging' in the afternoon. I wash my feet in the creek and since I feel already freezing cold afterwards I continue with a 'full-body-wash', including a shave. Pieces of ice at the edge of the creek increase my pride. The sun is hot, but a breeze makes it very pleasant.

Lying in the sun warms me again just in time before fog moves in from further down. Temperatures drop quickly and the most comfortable place is the sleeping bag with a hot water bottle at the feet. My body has adjusted well, I am not cold at night and when I touch my fingers after an hour of writing I am surprised that they are freezing cold, they felt warm the whole time. Also my bruised hand has healed very well in just two days.

After dinner I crawl right back into the sleeping bag, falling asleep takes longer than the usual 3 minutes, probably because of the altitude. We are spending the night almost at the height of Europe's tallest mountain!

Dharamsala - Larkya La - Bimthang (Day 17)

The two French groups left early, making enough noise to wake me up. The fog is gone, the stars and moon turn the mountains into a fantastic strange light. We get up after they left, pack our things in freezing cold and leave at 600 after a simple but nourishing and excellent tasting noodle soup. It is not as cold as I feared, and since the sun is about to rise it is also unnecessary to walk with torchlight, making this a normal walking day. Sometimes there are reasons to start early (time to turn around in case of problems, too much wind on the pass etc.) but often it scares people unnecessarily. Some people - not in our group, but in general - get a bit paranoid when they have to cross a pass.

I will try to push myself harder today to find out how strong I feel and pass the others after a few minutes. One hour later the sun hits the first summits to the left, slowly turning the range into an orange light as I get higher following the moraine. A frozen lake reflects the mountains, soon afterwards I reach a small plateau with fantastic views. Unfortunately, I have caught up with the French already, which is reason enough to leave soon afterwards. Ahead of me is a gentle slope that widens as it gets higher. A small trail is going over endless fields of rocks and boulders. The contrasting scenery to the left and right - high mountains and the beginning of the Tibetan plateau on the other side - is stunning, but the walk itself is rather dull and seems never-ending. Whenever I reach a little ridge, all I see are more boulders and stones to stumble over.

After another hour I can see a ridge near the horizon, the few colorful dots are hopefully prayerflags marking the pass. When I get there the view is not as spectacular as I hoped and I go on to what looks like a 'second' pass a few minutes ahead. It is absolutely amazing, a huge mountain range goes from left to right, followed by enormous peaks that form the border to Tibet. Behind the Kichke massif the very top of the Lamjung and Annapurna range are visible, with one peak clearly standing out. Glaciers seem to fall down the steep flanks of Cheo Himal on the right, resembling huge frozen waterfalls. The glaciers from the range to north have created several moraines far down in the valley, three of them flow together like rivers. A dark green lake between the moraines stands out of the ochre and white tones.

It will be a steep descent to camp, losing almost 5'000 feet in two hours. First we get down on an unstable gravel slope, then on a very steep trail that follows the ridge high above the moraine. When we reach the moraine we stop for a short break and a mini-lunch. The sun is burning and I soon leave because it is too hot without shade. It is another hour to the campsite on the moraine's left through fields of large black boulders. Then we reach the ablation valley near Bimthang. The views are just breathtaking. A shallow creek meanders in this lovely valley between the moraine and the wall of the main valley. Clouds have built up, but I get to catch a glimpse of the fantastic mountains that rise high in the sky, the flat plain of Bimthang increases the sheerness of Pungi (Kampung Himal).

Bimthang used to be a trading place during the summer months when goods from Larkya Bazaar and from the Marsyangdi valley were exchanged here. Nobody else lived there for the rest of the year, since there were not fields for agriculture or rich meadows for husbandry, and during winter months high snow made travelling and trading impossible. Times change and these days it is tourists that come here - not many but enough to make the three shops and lodges a lucrative business.

If the clouds disperse I will walk back again for the views, but right now I enjoy the warm fire in the lodge of two chatty Gurung girls, Gita and Ganda. They are friends from Tilche and stay here for the tourist season, looking after their parent's lodge and shop.

I will probably take awhile for the porters to arrive. This would be good excuse to spend the night in the lodge where I already reserved a good spot near the fire, successfully defending it against the two porters who are also very eager to sleep here. Later I give up my spot because the tents and my bag have arrived, and because I do not want to spoil the party that - as it turns out - goes on till very, very late.

Bimthang - Soti Khola (Day 18)

Nice morning views again; the range to the north has some fog drifting in front of it, making the mountains more impressive. Another 360° panorama. It was cloudy since yesterday evening, and a cold wind destroys all hopes for 'post-pass-warm-holidays'. The fire in the lodge is the best spot to wait for the fog to burn off, and the two girls are fun, though I speak no Nepali and feel a bit stupid.

I would like to walk up to the green glacial lake, but it is not a 5-minutes walk away as we were told. Nevertheless, the views of the glacier from top of the moraine are nice. Two huge peaks of the Kampung Himal rise above the clouds, but haze blurs the views. A white river flows down in a riverbed of white-pebbles, giving it the name Dudh Khola (dud means milk in Nepali).

We cross the bed of the old glacier and enter an enchanting forest on the other side. Huge firs with moss are predominant at first, but the variety of plants grows as we get further down - bushes, ferns, and deciduous trees. The mountain views are fantastic and much better than I expected it. Manaslu stretches high into the sky, the glaciers and moraines come down a long way and end just above the steep wall of the Dudh Khola valley. The mountain looks very different from here, instead of an even pyramid it seems to be a huge square with the two peaks sitting in the middle. It is worth going slowly, the views are so stunning that I stop often and watch for a long time. The hills in front of the Manaslu range add to the diversity of gray glaciers and white summits, a green hill with dark trees stands next to a brown hill with white birches. The peaks slowly disappear in the haze, and we get further down in the valley that becomes narrower. Walking in forests is pleasant after the barren high country. It is overload for the senses: all the colors, fragrances and sounds are overwhelming after days of brown and gray tones where the howling of wind was the only noise. In two days I will probably wish I were back above the timberline, but right now it is a real joy.

The afternoon is a bit dull, but luckily short. Grey clouds hang in the valley, it gets chilly soon. Having crossed the pass was a reminder that this trip will 'soon' be finished, and at camp 'post-pass-depression' comes over me. Luckily it goes away quickly after taking a luke-warm shower and spending an afternoon with biscuits and tea over a good book.

Soti Khola - Danagyu (Day 19)

We continue to follow the Dud Khola down to the Marsyangdi valley. There we will hit the popular Annapurna Circuit. The creek slowly turns its color into a blueish gray, at first the walk is interesting because of the different plants and the mountain views, but then its get a bit boring compared to other days. The gorge allows for little cultivation, so the number of houses is small. Except for a guesthouses they are all deserted, people moved back to Tilje or maybe even further down to Pokhara or Kathmandu as winter will arrive soon.

After two hours I get to Tilje, the first larger village since Samdo. The houses are quite elaborate, more wood is used as building material and people pay more attention to its appearance. Landslides and rockfall have destroyed the last part of the trail. Just afterwards a bridge leads to Thonje, a town with a large school just opposite Dharapani. Ang Dami is waiting there, he went ahead yesterday to sort out the gear and organize things for the next week, and our climb. Some of the loads are left behind and will be picked up on the way to Besisahar in a week. Our liaison officer Manjul is leaving here, he was the most pleasant officer I met so far, and he seemed to enjoy the trek. Sometimes these officers are in a strange position, shunned by tourists and the crew, but luckily this was not the case here.

We are on one of the most popular trails in Nepal now. This part of our trek is a much bigger letdown than I expected; the wide trail is littered and full of horseshit, the scenery is not especially nice and the weather not fine either. We pass a few villages with endless shops and guesthouses and stop in Danagyu. Staying in a lodge feel like betrayal, although it is nice and clean it feels like an unnecessary luxury. The crazy drunk guy kind of fits into this day. Somehow such a letdown day belongs to trekking, it helps to appreciate all the other great days we enjoyed and will make the ones ahead of us even better.

Danagyu - Bratang (Day 20)

The walk in the morning is much nicer than the one yesterday afternoon. We follow the river upstream through forests; the scenery is familiar to me, but if you are here for the first time it is very impressive, at least the tourists I meet on the way are just excited.

When the first peaks of the Annapurna massif rise above the forest, it becomes more interesting, the scenery changes more often now. Some landslides took out large parts of the trail, but now the path is in good condition again. Shortly before Kudo, a nice-looking Tibetan village, the views of Annapurna II are fantastic. A very narrow gorge branches off to the east and goes to Nar, a totally restricted area with some remote villages.

We have met some tourists, but not the hordes of ignorants that you would expect on this popular trek. The stores in Chame have an incredibly selection, you can get everything here. It is a culture shock, but a pleasant one. We all stock up on chocolate, Tang, and every other snack you can think of. The village girls seem to like me and we exchange many, many smiles.

Two portions of fantastic dal baht later we start for a long afternoon. After climbing uphill for some time I meet a monk and am surprised that he speaks Tibetan. An old couple from the village joins us - I feel like the worst part of the Annapurna Circuit is behind us now.

It gets cold after the sun disappears early, making this a day where the purpose of walking is to arrive somewhere and you don't do it just because it is fun. Nonetheless, this day was much more pleasant than yesterday. The views were nice, the scenery was interesting and the villages less out of place. After three weeks of walking I usually have a day or two when I do not enjoy trekking as much as on the other days, but tomorrow I should be fine again.

When we reach Bratang I realize that I camped here about ten years ago. The 'town' still looks a bit poorish from the outside. But the house of the didi's family is very comfortable. She is a 19-year old Gurung girl and has to do all the work since the others are not a big help, This leaves little time for conversation, which is a pity because she is really cool. [Sita Sherpa Gurung] Originally the village was founded by Tibetans resistance fighters that were attacking Chinese troops from the Nepali side of the border. Nothing reminds me of that past, though.

Bratang - Upper Pisang - Ghyaru (Day 21)

Most people had a hard time sleeping because horses with bells kept passing just below the lodge till late in the night. I usually wake up easily, but am happy to get up as usual half an hour before breakfast tea. The ridge of the Annapurna range is reaching above the timberline in the form of a narrow orange stripe between the blue sky and the green forest.

The trail is chiseled in a vertical rock face, a very promising start for today. Below the steep smooth curved rockface of Paungda Danga we cross the river and after an hour in a pine forest more and more mountains become visible. Shortly before Pisang we overlook the wide valley with its organ-pipe erosion and white peaks higher up. It was a nice walk in the shade of the forest, but I am happy that we take the high trail now and climb up to Upper Pisang after crossing the blue Marsyangdi river. The fort-like houses with Chulu East behind are a great view. Because most tourists take the lower trail, the town kept its authentic look and not a single brightly painted shop hurts the eye. Most people have left for the lower valleys, making the walk around the village very short. A new monastery is being built, though the old one looks very nice. The ground floor is used only a few times a year, most notably for Losar dances (Tibetan New Year festival in February). The first floor is a gallery with views down to the dancing room. Above it is the gompa, it is rather small and filled with modern bauble and souvenirs from Bangkok that do not fit in.

After a short descent we are back in the forest and pass a long mani wall. High above on the right is a white monastery. It looks like a strenuous and long climb, but once you get going, zigzagging up the hill is easy and fast. When I reach the three white chortens I am surprised to see not only the gompa but also a large village. I thought Ghyaru was much further away.

The village is similar to Upper Pisang, but the houses are built together much closer and the town seems very 'untouristy'. It is fun to walk through the narrow alleys looking for interesting things. The gompa on the upper part of the town is locked and while looking for the caretaker I hear the murmuring of people praying. I climb a long and steep ladder - of course only after unsuccessfully calling for somebody, I am trying to be polite and also I do not want to meet a snappish watchdog up there. In a small building on the roof are a few monks and a nun I met in Chame reciting texts. They read them from scripts, everybody seems to have a different book. It is probably also a ceremony for protection and a whole liturgy is being read.

When I want to go back down I find it almost impossible to use the ladder. It is too steep, the notches are too small - I would probably lose my balance and fall down 10 feet to the ground. Luckily the house owner sees me and lets me climb a small fence on the roof, so I can take a regular staircase and walk to the guesthouse. By now everybody has arrived and we decide to stay in the nice lodge because there is no campground. That is why most groups take the lower trail, and for some strange reason even individual trekkers prefer the lower route.

I walk up to the gompa an hour later and an older man is there to let me in. The monastery is much nicer than the one in Upper Pisang, but the caretaker is not very knowledgeable. After answering many questions in Tibetan he explains that the Panchen Lama is the head of the Nyingma sects - which casts doubts on all the previous answers he has given. On the way back I meet the Tenzing, Ang Dami and Bharat, and walk around the village with them. It is their first time in this village, and they say 'now we are tourists, too, and want to look at everything'. That is really cool, and after twenty minutes Bharat finds a nice house where we can warm up in the kitchen.

The family is originally from Tibet but fled in the 1960s and settled down here. One of the children lives in Germany, but I do not know him (it's a small world and it wouldn't have been surprising to have met his son). It is great to sit around the fire and talk to the couple and their two grand-children. When I run out of Tibetan, the conversation switches into Nepali and somebody translates. These 'kitchen-experiences' are new to me, spending evenings like that has made the trek much more interesting because the time in camp is usually not very exciting. Of course it would be more fun without any language barrier at all, but I am doing fine with a little smalltalk and often somebody can do the translation. After some cups of butter tea we say good-bye, and I get back to the lodge.

It is rather chilly, even inside the lodge, so after hot soup it is a good idea to go to bed early.

Ghyaru - Nawal - Waterfall camp (Day 22)

I hoped for a fantastic sunrise - I still remember getting up early in Braga some years ago - but it is freezing and not worth it: Sunrise passes without illuminating the mountains. I guess we were really spoiled with fine weather if I am complaining about things like that. The Annapurna massif does look fantastic, one huge peak is connected to the next one by a fine ridge.

The village looks very nice in the morning sun, steep barren fields surround it and the white Pisang Peak rises just behind. Many people think it is the easiest trekking peak in the area, after looking closely at its steep flank just before the summit I really, really hope that they are wrong. I want Chulu Far East not to be any steeper. Prayerflags higher up indicate a religious monument, but I am not too keen on exploring and stay on the main path. The mountains are incredible, Annapurna II, IV, III and Gangapurna are very close, further north is Tilicho. In addition to the mountains we see the rugged Marsyangdi valley with forests, washed out canyons and the barren mountains at the far end where Thorung La crosses over to Muktinath. To the south is the sheer carved rockface of Paungda Danga, Lamjung Himal and at the horizon is a peak that resembles Himal Chuli.

On the traverse to Nawal we pass some girls selling biscuits and cokes up here in the middle of nowhere. Hopefully they are is busier in the high season, only few trekkers take this trail and they are probably not craving for biscuits. A chorten announces the village; situated on a flat valley confined by organ-pipe eroded walls and high peaks in the background, it is one of the many fantastic views of today. The ridge of Chulu East does not look too difficult, but I guess mountains always look easy from miles away. The old gompa is not very interesting, it has been replaced by a newer one that also serves as monastic school, and maybe all the nice statues and thangkas were moved to there.

We leave the Annapurna Circuit now and take the trail to Chulu. On the way there we pass a village that is on no map, it seems completely deserted but the colorful prayerflags indicate that at least three houses are still inhabited. Then we pass the most beautiful chortens of the entire trek, they are very well-kept and built in a style often found north of Muktinath: white washed with paintings and red wooden frames. In a little sidevalley lies the village Chulu, the creek that flows by comes from two waterfalls further up where we will put up our camp. On the way down I hear much laughter, it comes from young monks who are carrying large trunks of firewood to their school. The large building is a branch of a Kagyü monastery in Kathmandu. Hopefully we will have an extra day before flying out and I can spend some time here.

The lunchspot is great once again; a creek, red bushes and birch trees in front of the few Chulu houses with large yellow haystacks on their roofs. A canyon with firs on its top rises beyond the village, the steep flanks of Annapurna III and the white pyramid-shaped summit of Gangapurna are in the background. The light is not very good, otherwise this would be a potential 'picture of the year'.

After a good lunch at this lovely spot it is just one more hour to waterfall camp. The hike along the Chegaji Khola is lovely, the steep and barren hills and snowridges are quite a contrast to the pleasant atmosphere in the enchanting forest down here. The porters are a bit grumpy because we do not stop at the first campsite and go on for a little longer until we camp close to the two partly frozen waterfalls. But their faces light up when they see the small stone hut and a huge dry tree in the fireplace.

The sunset on the Annapurnas is a fantastic view and a reminder to put on some warm clothes. It is really chilly soon and we all gather round the large bonfire. The group will be splitting tomorrow: Dagmar, Tracey and Lizzy will go down to Braga; Dana, John, Tom, Jamie and I attempt the peak and will set up camp at around 5'000m. Spending an evening around a cozy campfire is a perfect end of a great trekking. Somehow the group never became close-knitted, but we had a nice time together and avoided any fights or arguments. For some the novelty has worn off after three weeks and grumpy moments happen more often than in the beginning. It is -10° C, but the cold is driven away by warm clothes, the fire, hot soup and excellent dal baht. And once you are in the sleeping bag you are warm anyway. Well, except for the damned 'latrine-calls'. My equipment-list is almost perfect but still has room for improvement: Tang powder, green tea leaves and a pee bottle will definitely be on the next version.

|

Summary Part 4:

After Sama the scenery becomes desert-like and treeless. The glacial valley takes us even further to the Tibetan border, though a last barrier of 'low' hills blocks the views of the high plateau. Refugees from Tibet built their simple houses in Samdo fifty years ago. Since agriculture is not possible on a large scale, they make a living as traders, and have more leisure time than people in the villages further down. They are very friendly and hospitable. The next day we continue towards the highest point of the trek (excluding the climb, of course) and set up camp at the last house before the pass. Larkya La is an easy pass, thanks to a gradual climb along a moraine. It is not only the passage between the two valleys to the east and west, but also stands between the Himalayan range and the Tibetan plateau. The views are literally breathtaking. After a steep descent we reach the old trading place Bimthang. A shallow creek meanders in this lovely valley between the moraine and the wall of the main valley. Mountains rise steeply in the sky, the flat plain increases the sheerness of Pungi (Kampung Himal). |