MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

The twin-peaked Nun (7'135m) and Kun (7'134 m) are the highest mountains in

Zanskar.

Its glaciers run far down into the valley and end just across the river near the

road.

Stunning meadows with dozens of different flowers.

Wide valley near the hamle of Yüldo. The chortens represent Vajrapani (black),

Avalokitshvara (white) and Manjushri (red) and announce that we have left the

Muslim-influneced part of Ladakh behind us and enter the predominantely Buddhist

Zanskar.

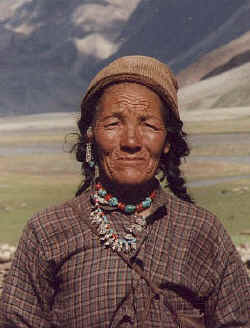

Old Zanskari lady who leads the households of Yüldo.

The horses from Yüldo have a reputation of being the most suitable ones for

playing polo.

The wide valley of Yüldo is surrounded by steep walls.

The higest pass so far: from Penzi La (4'401 m) the glacier

Zanskar: Kargil - Padum

Kargil - Yüldo - Padum

Kargil to Yüldo

Two more days on the road before we finally reach Padum, capital of Zanskar and start of our trekking towards south. The drive out of Kargil is so much more pleasant than the drive to Kargil the day before. The road is getting worse, but the scenery is more interesting. We drive along the Suru river south. Many villages lie next to the river and people are busy harvesting barley. The number of fields is enormous, I wonder how so few people can cultivate so many fields. Then I see the first tractor since I've been here and I know how they can do it.

But in most villages, farming is how it's been for hundreds of years: husbandry season starts in May, after all the snow from winter has melted. A horse or cow drags a wooden plough and natural fertilizers are put on the ground. Men and women usually do the same work throughout the year, only the physically demanding ploughing is done only by men, while women plant the seeds. Depending on the climate, the harvesting season begins in early August or September. The ears are cut with a small sickle and laid on top of each other in a special way to protect the wheat from birds. Threshing is done by having cows or mules walk over the ears . To separate the wheat from the chaff, the farmers throw it high up in the air. It's always windy up here, the light chaff is blown away a few feet while the heavier wheat falls straight back down. "Food without salt is like work without fun", says a Ladakhi proverb. And really, everybody is singing or whistling on the fields. Apart from making the work easier, the singing has a social function as well, I think. It's not like in Europe where every farmer works only his own field. Six to ten houses form a Paspun, a very small local community that helps each member, also during harvesting. Members are closer than relatives who live outside the Paspun, true to the proverb "it's better to have a bad present neighbour than a good absent relative". Often there are ten people working on the same field. Work days begin at dawn and end at dusk. Time is running short, the harvest should be in the granary before the cold winter days begin.

Instead of monasteries there's a small mosque in almost every village. Soon Ladakh's two highest mountains can be seen: Nun (7135 m) and Kun (7134 m). The surrounding mountains are also quite high, one glacier is so long it touches the river we're driving along.

In the afternoon we reach a broad, long and totally flat valley which stretches from east to west. All of a sudden prayer flags, chorten and a mani wall appear. A mani wall consists of many stones which have the famous prayer 'o mani padme hum' inscribed on them. They are made during the long winter days when people stay in their houses. The length of those walls is often stunning and shows the important role of Buddhism even today. We leave the Muslim influence behind and enter Buddhist territory again. The village of Yüldo consists of three houses and is very idyllic, but we drive past it without stopping. Luckily five minutes later we find a nice camp site. I don't fully realise the beauty of the valley until I get out of the bus. It's very quiet except for the broad rivers rushing and the birds singing. The high mountains around us look as if they are protecting this place. It also feels like this here. I walk back to the village. Everybody except for an old couple are out looking after the cattle. The old woman wants eye drops, but I don't have any. What she probably really needs is a pair of sunglasses, but I still need mine.

She has laid out barley to dry in the sun.. Later the barley will be ground and roasted to make tsampa. Her husband comes out of the house, looks at us for a minute with not too much interest and walks off aimlessly. But I guess people up here have a purpose for everything they do, it's just not as easy to see because they do things more calmly. People aren't aggressive or pushy or in a hurry, which can lead you to the wrong conclusion that what they do is not very important. So when he slowly walks up a mountain he's not just strolling around because he's bored, he might be looking for herbs. Of course he could run around (if he still can at his age) and try to collect more herbs, but what good would it do him? Tiny observations like this make me think. On the walk back to the campsite I see the family's cattle. Many animals graze here; cows, dzomo (a mix between a yak and a normal cow), yaks, sheep, goats, even small horses. Horses from here are famous in Ladakh because they are said to best ones for polo, therefore they cost about US$ 800.-. There seems to be an abundance of grass and water, but when Islamic nomads from Jammu sent their cattle up here a fight occurred. It led to a shoot-out in which some people were injured.

The valley is also well-known for its herbs and flowers. Doctors in traditional Tibetan medicine come here in summer to collect rare herbs, the number of flowers is really big. The smell up here is refreshing. It's so nice to walk after those long hours in the bus. A few clouds block out the heat of the sun, but the wind is not too cold, . The evening mood is amazing. When you sleep in a tent you're so much closer to nature and start to notice and pay attention to small details.

Today is the first time our cook and his assistant do the dinner. It's surprising what they cook on their two little gas stoves. Rice, lentils, cauliflower, soup and a salad. The cook's name is Indhar, the assistant cook is his nephew and is called Bupandhar. They're from Nepal, near Pokhara. Dinner is great. But I have trouble sleeping, the first night in a tent is very different from a hotel. Every noise - and there are many, too many - seems to wake me up. Birds, the river, the wind - everything is too loud and unusual.

Yüldo to Padum

I haven't slept well and when I feel tired enough to get some real sleep it's 6 o'clock and almost time to get up. The air is very clear, the sun turns the steep mountain walls and the broad valley into a beautiful light. This is the last day of driving, we have one more pass to cross, then we'll come to the largest valley in Zanskar and soon after that we'll get to Padum. I'd rather walk than sit in a bus the whole day. But I'll get more than enough walking in the next few days. We drive towards the Rangdum monastery, which stands on top of the only hill in the valley and the end of it. I'd say it's a castle if I didn't know that it's a monastery. Its location seems to be nicer than its rooms, otherwise we would have stopped for sure.

We're on our way to the pass now, the scenery doesn't offer much of interest, apart from amazing mountains of course. Soon the Penzi La is crossed, the 4'401 metres is the highest altitude so far. Mont Blanc is about that height. The pass is the natural border between the districts of Ladakh and Zanskar. On the right-hand side the enormous glacier Durung Drung crawls into the valley. It's the well of the river Stod which makes life in the valley possible. This side of the pass is very different from the valley at Rangdum. It's steeper and more stony. It also seems less fertile, but there are more villages along the road.

We stop for lunch. A very warm wind together with the smell of all the different flowers make me feel like I'm in southern Spain. Sitting in a meadow full of flowers, enjoying the sunshine and having a great lunch. The whole village seems to be watching us. An old women talks to our bus driver. Then she starts pushing and shoving him and he runs away, much to the amusement of everybody. He looks pretty embarrassed. She argues with him, apparently she wants his shirt but he's not willing to give it away and hands her a few rupees instead. But she's too proud to take it, so he just puts it in her pocket. She chases him to give it back, it looks so funny that people start to laugh even more. Somehow they reach an agreement and she keeps the money.

Half an hour later, all of a sudden there this phhhh sound and the bus shakes. A stone has slashed a tire. The twenty minutes it takes to fix it is a nice break. We should've made more short stops, especially at nice places to take pictures and to walk around for a few minutes. When I see all the fields down in the valley near the river I understand why more people live here.

An old man walks by and asks me something. I don't a have a clue what he's saying but I firmly reply: "Padum," which seems to be a good answer, since he nods his head and says: "Ah, Padum." I'm extremely proud of myself. Two minutes later another old man stops for a second and talks to me. My standard answer 'Padum' doesn't seem to fit this time, he looks puzzled. He actually wanted to know what has happened to our bus. Well, one out of two is good enough if you consider that my knowledge of Ladakhi consists of 'Julay' and a few words for food and water. Julay is the magic word, it means hello, good-bye, good morning, and thank you.

Padum with 70 houses and a population of 800 people by far the biggest town in Zanskar, lies in a big valley. Actually it's three valleys that meet here and form a large, completely flat area. It's so big that not all of it can be irrigated and used for pasture, therefore a large part of it is desert. When we get there, a storm is coming from the south. It's not raining yet, but it's very windy and small sandstorms can be seen. Due to this and the fact that people have had things stolen out of their tent we stay in the best hotel of Padum.

Hotel Chorola hardly deserves the name hotel. And even though it could be compared to a construction site it can be turned into an (almost) cozy place with some fantasy. The rain and wind are kept out, which is the important thing. The village of Padum isn't very attractive either. It's a typical transit village. It's the only Islamic village in the valley, 75% of its population consisting of Sunnit Muslims. In 1975 severe riots occurred and could only be stopped by flown-in public figures from Leh. Muslims had caught and eaten fish from a lake considered sacred by Buddhist. Buddhists threw stones while Muslims prepared their guns. Luckily, a big clash was avoided. Today both groups live together in harmony. There's not much to see in the village itself. We have a rest day tomorrow and there'll be enough time for a day trip to explore the valley.

Padum, Karcha

During the night a spider walked over my face, the wind pushed open a window and it rained on my bed and at four in the morning the Muezzin of the mosque woke me up with 'Allah, oh Allah' prayers over the mosque's p.a. system. I think Christianity's custom to ring the bells on Sundays is pretty selfish, but Islam beats that. The good news is that last night our horses arrived. Actually we have 5 mules and 5 horses to carry our big backpacks, the tents, the food and gas for the stove. Two ponymen will come with us, Raijiv 1 and Raijiv 2. The younger one should probably be in school instead.

We're in the center of Zanskar now, which is even more remote and harder to reach than Ladakh. For more than seven months a year it's cut off from the outside world. Only during the few summer months when there's no snow on the passes is it possible to get there, either by the only road or by foot. Snow-capped mountains are far more numerous than in Ladakh, their different forms and colours seem endless. There's an abundance of glacier water, desert-like areas hardly exist. People use every flat area for agriculture, but since the fields are at a higher altitude and it's colder here, things don't grow as fast as in the valleys further north.

The few things that are known about Zanskar's history come from legends, which certainly have a bit of truth in them. A long time ago a huge lake covered the area. After the water level had sunk, people from Tibet and Mongolia settled down. They were hunters whose gods were the sun, the moon, the earth and some gods from the animal world. It took them a long time to discover agriculture and build villages.

The legendary king Gesar, a friendly god of war, destroyed the evil ghosts in the area. After that, Padmasambhava came to Ladakh in the 8th century. He fought against a man-eating monster - the demon lost. When it fell fatally wounded to the ground, it had the shape of Zanskar. To celebrate his victory, Padmasambhava promised to meditate on the dead body. At the location of the head, chest and feet the first monasteries were built. Zanskar's religious connections were with Kashmir, but when Kashmir became Muslim, relations with the much bigger Ladakh became more important. Later Zanskar was overrun by the Ladakhi army. The same Indian troops that occupied Ladakh in the 19th century also took possession of Zanskar. Many of the invaders descendants settled down in Padum and that's how it became the only Islamic city in the Buddhist area.

Due to its geographic isolation, the culture has remained more intact than in Ladakh. Buddhism plays an even more important role in Zanskaris' lives. But since there are only 5'000 people in Zanskar, the number of monasteries is more 'moderate'. The largest one, Karcha, is where we go today. It's on the other side of the valley, about 2 hours by foot. The area is very flat, and once we're out of Padum and have walked for half an hour the desert begins. Although it's still morning, it's already hot. In the far distance I can see whitewashed houses, the monastery is built a little bit above the village. But Karcha doesn't seem to come any closer. Finally, we get to the river after two hours; it's only a steep climb now and we're there. With its 70 houses it's the second biggest village in Zanskar, and one of the oldest. The monastery seems to have more buildings than the village. About 120 monks live here, which makes Karcha the largest and richest monastery; almost half of the fields in the valley the belong to it. The Indian government initiated a land reform with the goal to take land away from big landowners and to give it to people with little or no land. But local farmers protested against taking land away from the monasteries, so monasteries remained as wealthy as they were. Today farmers have to give about 15% of the harvest to the landowner. Karcha monastery was built in the 11th century and has quite a few interesting buildings. In two weeks there is a big dance festival, people from all over the area will come to see it.

Monks have just repainted the masks which will be worn at the festival. Most probably the dance will show the introduction of Buddhism to the region and the main person will be Padmasambhava. They show the victory of Buddhism over the old, evil ghosts. There's one especially remarkable scene in those dances, where Padmasambhava takes a sword to fight a demon. But he doesn't kill the demon as you might expect, he just destroys the demon's blindness and ignorance. Once the demon's hatred is gone, he's not dangerous anymore. Isn't it like this in real life? Those Cham dances are performed all over the Himalayan region and last a few days. Too bad I've never had the chance of seeing one.

Unfortunately, the keeper of the key isn't in the monastery, so we don't get to see what's inside. But the view from the top is reward enough for the long walk. Desert, red mountains, Padum with its green fields and high mountains in the far background make this a marvellous scene.

|

Summary Part 1:

I am happy to leave Kargil and be on the road again. We drive through small villages with minarettes where the people are busy harvesting. The glaciers of Zanskar's highest peaks are reaching far down into the valley, literally stopping at the road. The wide valley at Yüldo is another highlight, soon followed by the glacier near Penzi La. That pass marks the historic border between Zanskar and Ladakh, the ride down to Padum offers great views over the plain.Various towns are built on the hills surrounding it. Zangla would be worth a visit but we do not have time, therefore we walk to Zanskar's largest monastery, Karcha. The next day we enter the Lungnak valley and follow the river towards south. |