MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

Pyramid mountain looking out of the mist.

The small village of Kargiakh seems to be the most populated town south of

Padum.

Fine rock carvings are often done during the long winters where people cannot do

any work outside the house.

Starting the ascent of Shingo La: The good weather quickly gives way to light

snowfall.

Fog and snow are getting stronger with every minute. After an hour we are lost,

one pony limps, the horsemen are crying, but luckily two locals with their yaks

have followed our path and pass us, leading the way.

Probably my most strenuous and least glorious pass I have ever climbed: Shingo

La, 5'051 m

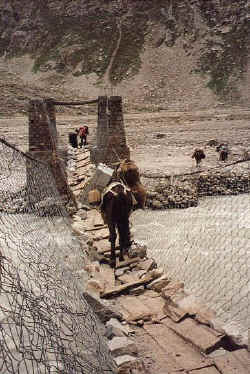

Bridge before Zanskar Sumdo, getting the mules to cross it takes some time.

From Zanskar Sumdo it is an easy and enjoyable walk to Dharcha. The Manali-Leh

highway passes the village and we take a bus to Manali, regretting to have spent

only three weeks in the Indian Himalayas.

Zanskar: Purne - Shingo La - Manali

Purne to Kargiakh

I have had a bad night. My stomach is rebelling against something I've had for dinner, and the three dogs we've picked up on our way from Rera are barking like crazy. I have to get up a couple of times and can combine this with throwing stones at the dogs (but of course trying not to hit them) so they'll sit in front of another tent. The weather seems good at first, but then I look in the direction we're headed today. Dark, grey clouds - or better a wall of clouds - let me know this won't be a pleasant day. And I'll be right.

The first 30 minutes are hard work, a steep climb but then we reach a broad fertile valley. Barley and potatoes grow here, though the climate doesn't seem to be good for agriculture. The barley is still small. I hope people can harvest it before the cold days arrive. We walk past Jal and Tela, but the villages are empty, most people are working on the fields. They are very friendly, only kids get on my nerves with their "bonbon, school pencil". After almost two hours we've passed the green oasis and are walking through a stone field. Nothing but stones, stones, stones for more than an hour. We cross the Kurgiakh Chu, which we've followed since Purne, and walk through a similar landscape for a short time. I'm relieved when I see something white, a chorten. Often they are placed at the beginning of a village, and no matter how small the villages are there's something to see.

We're at Tanze and have done half the distance in less than 3 hours. Phunchok seems a bit worried that we're too fast for the cook to catch up, so we wait. He doesn't show up for over an hour. I get a bit restless, it starts drizzling and I'm sick of sitting around. Finally he arrives, but without his assistant. Another horse got sick and Buphandar is walking with them. We want to go a bit further before lunch, it's only twelve o'clock and nobody is really, really hungry. The drizzling changes into heavy rain and we stop at the next house, luckily it's close, only half an hour away. The people are very hospitable and we can have lunch here.

It's a typical house in the countryside. With its small windows, a tiny door and thick walls it resembles a fort. But this form of architecture is very effective - in winter the cold is kept outside while in summer the rooms remain cool. The house has two stories and a flat roof. The roof is used as a storage room in the summer to dry fruit and vegetables. Basically it's considered a nice place to sit and work and people spend many hours there. On the ground floor are the stable and the room for the farming tools. A very small and narrow and absolutely dark corridor leads to a staircase which goes up to the second floor. It takes us directly in the kitchen. The door to the living room is about one foot wide and three feet tall, luckily we're all small. This is the best room of the house, there's glass in the windows, jewellery hangs on the walls together with scissors to cut sheep wool and a copper plate. We're offered a seat on the thick, heavy, comfortable carpets. This room is directly above the stable. This has the advantage that in winter the warmth from the stable heats the living room. But there's also a disadvantage that it smells of animal dung. I don't want to sound ungrateful, I really appreciate it that we can use the best room. But the stench is pretty penetrating. Not only is the whole family watching us, the neighbours are also here to see what those tourists do. We're ready to leave pretty soon. I walk down those dark stairs and am glad to find the hallway. But I take the wrong turning and walk straight into the stable. I've almost gotten used to the stench, but here it's so strong that I almost pass out. I find the right way in time and am relieved to be outside again.

The rain is pelting down stronger than before, but at least our horses and mules have arrived. Two of them can't carry anything now, but since we have less food and petrol than four days ago everything can be transported. The rain has increased even more, but what I'm frustrated about isn't the rain itself but the clouds. There's nothing to see except grey clouds and stones. We walk along a broad riverbed. The low hanging clouds look depressing, but the mind (or at least my mind) finds a way to deal with this: it just cuts out the 30% of the most negative and 30% of the most positive feelings and thoughts. I walk pretty disinterestedly, but without feeling bad about the rain and feel like I could go on forever.

After two hours my clothes are wet but my mood hasn't changed. Apathy can be good in a situation like this. We would have reached our campsite a while ago, but since we are walking with the horses we're still on our way at half past three. Hurrying would be senseless, since we would have to wait for our tents anyway. We pass a few villages, chorten and mani walls in the meantime, but it isn't enough to catch my attention. By now I'd be glad to crawl into my sleeping bag. Then I see a chorten on our side of the river. According to the map (which so far has been surprisingly accurate) it must be Kargiakh. We leave the path to walk down to the river and I think we're there. But we walk for another 20 minutes - an endless 20 minutes. The meadow along the river is nice; it's astonishing to see what variety of flowers grow here. We finally put up our tents in record time. My sea bag is totally wet but the things inside are still dry. One of the many useful things I've brought is bouillon. Lying in a tent in a cosy sleeping bag with hot soup while it's raining is even better than lying in bed for the whole day on a foggy Sunday in December. Hopefully the tent will continue to keep the rain outside and hopefully tomorrow will be a better day.

Kargiakh to Shingo La base camp

It rained cats and dogs the whole night. The tent is better than I expected it to be, though. I'm dry but it gets cold and I'm not comfortable in my sleeping bag. Supposedly it's good for -12ø C, but I begin to doubt that and hope I don't have to test it on this trip. In the morning the rain stops and a few spots of blue sky are visible between the clouds. Twenty minutes later it rains again. The sun tries to break through a couple of times but the clouds are too thick. I don't know anything about meteorology but I'm pretty sure all it would take is a little bit of wind to make this a sunny day. The rain is increasing. Group dynamics start to show, everybody walks on their own. I've seen a picture of this valley on a sunny day, it looked beautiful. The contrast between the green of the valley and the barren rocks above that fantastic. Ahead is the Gumburanjon, a 5'900 metres peak which looks fascinating because it is the shape of a pyramid and there are no other mountains standing in front of it. The river makes a strong right turn. So far every 20 minutes we've had to cross a small river, but despite the rain the water levels haven't caused us any trouble. Now we do have a problem: the melting snow and glacier water from the high mountains have lead to a rather big and strong creek. After five minutes I find a spot with a few bigger stones in the river, it seems jumpable. I've always been a good and confident jumper. Phunchok seems to be very worried though. Admittedly the distance from one rock to the other is big. Admittedly, the stones are slippery. Admittedly, a false step would be bad, very bad. I hear him saying 'be careful' when I jump. I make it. The others don't want to jump and look for another spot. It takes them a while, I'm freezing in the meantime. My coat can't keep the rain off anymore, it's getting damp. There's another critical river, but this time Phunchok doesn't let me jump. It gets windy, but the wind doesn't blow away the clouds. Instead the cold wind blows the rain in my face. It's miserable. This qualifies as a storm. During the walk I try to keep myself busy.

- Thought #1: I'll be tempted to smack the first person in Switzerland who complains about rain. All it does in Switzerland is cause a minor annoyance. Up here it is a health risk.

- Thought #2: Why am I doing this? I could be lying on a sunny beach, snorkling, scubadiving, surfing, enjoying the sun. Why do I make my life harder than it should be? I don't ask myself that in a bitter voice, though a bit of self-accusation lies in it.

- Thought #3: This is a game. I'm playing it and I will enjoy it.

- Thought #4: This is probably as close to survival of the fittest as it gets for a middle-class male at the end of the 20th century. I will 'survive' this with a smile on my face and a few good stories to tell afterwards.

I walk very fast since the rain seems to be getting even heavier. Snow-covered high mountains tower above me on the left and right, the roar of avalanches and landslides can be heard. The only real power is nature, humans are so small. We reach a bridge and are basically at the campsite, instead of 5 hours it took me 31/2. Phunchok walks to the bridge to wait for the others, while I sit and freeze in a tent. It will take some time for the horses to get here. There's nothing to do but wait for dry clothes. I'm wet to my bones. I'm hungry. I'm thirsty. I'm tired.

The horses arrive an hour later, which is a pleasant surprise. They don't use the bridge though; instead they go walk through the river. Now I see how deep it is, water goes up to the horses' bellies. The current is very strong and the horses can't see stones or holes in the river. I watch in excitement (and admittedly fear) when it's 'my' horse's turn. Can it make it without stumbling? Yes, I'm relieved. We set up another record time in putting up the tents. It's windy, cold and still raining.

One hour later, the world doesn't look grim anymore. I'm in dry clothes, have drunken a litre of water, a litre of hot bouillon, a cup of hot chocolate and had great, hot lunch. Now I'm lying in my sleeping bag, enjoying every second of today. It's incredible how little it takes to make you satisfied up here: a dry warm place to rest, food and something to drink. That's all. And the rush of happiness when you have all those things just doesn't exist in normal life. The (temporal) lack of necessities makes trekking that interesting. And those fast changes from misery to happiness are just amazing. The mind simply works differently, it's clearer and somehow seems more receptive. For a little while it seems that the sun comes out, rain stops and it gets very bright. But two hours later clouds are as dense as before.

We've reached the end of the valley. It's like an amphitheater with a big entrance (the valley) and steep rows of seats (the mountains around us). The snow and white clouds make it almost impossible to say where the mountains end and where the sky begins, strange scenery. We're camping at the base of Shingo-La at an altitude of 5'100 m the lowest pass through the Himalayas. Our plan is to cross it tomorrow. But if the weather doesn't improve we'll have to wait another day or two. It's too dangerous otherwise, not necessarily for us, but for the horses. We're at 4'600 m and since there's not much else to do I take my pulse: 72. That's great, I'm glad I have adjusted that well to the high altitude. Doing all this with a headache or even worse health problems must be hell. Now that my basic needs (shelter and food) are satisfied I want the clouds to disappear, five minutes would be good enough. I just want to get a glimpse of the landscape. The colourful flowers must look great with the white mountains in the background...maybe tomorrow.

Shingo La to Ramjuk

Can things get worse? You bet. I wake up in the middle of the night, don't hear the sound of rain on the tent and see that it's bright outside. Great, a clear sky, the moon is shining. I get out - and my feet sink into a few inches of snow. Do we really have to stay here for another day? We'd planned to leave at seven o'clock in the morning, but at breakfast the cook thinks we won't go. The ponymen definitely want to stay, we tourists want to go and Phunchok is undecided. I woulndn't want to be in his position. Two hours later we leave in high spirits. The clouds have dissolved and we see the sun and blue sky after two days of rain. A steep climb takes us up to a plateau, there'll be a similar climb up to the pass.

We meet two hikers from Poland who've camped here for two days because they didn't know exactly where they were, the weather was bad and they were exhausted. The blue sky is gone by now, it's cloudy again. Soon we reach a big snow field. We walk with the horses today. After a few minutes the snow is one foot high, then two feet. Walking at this altitude in deep snow is strenuous, especially since I'm the second person and can't use any path, the ones at the end of our caravane have it easier. It starts to snow, it's foggy and windy. I love this, this is adventurous. Visibility hasn't been good for two hours, but suddenly I realize that we can't see anything. The fog and snow are so white that there seems to be a white wall around us. For two hours we walk up and down in zigzag course, to find the best way for the horses I assume. After another 45 minutes there's still no pass. Actually, there's nothing apart from the 'white wall'. When I see Phunchok pointing in one direction and Raijiv, the ponyman, pointing in the opposite direction I know we're in trouble. Things are clearly out of control. We're not in serious trouble, we could still walk back, but it's enough to give rise to a feeling of anxiety and fear. We're lost at 5'100 metres in a snowstorm. And if things are out of control at this altitude, serious situations can arise fast. It's a strange atmosphere, nobody feels comfortable anymore, some have reached their limit. Indhar has been sitting down every twenty minutes and complaining, the younger Raijiv starts to cry. It's almost two o'clock, we've walked for almost four hours.

Then, to everybody's relief, we hear voices and can make out another group of horses. They've just been following us, but since they're true locals they should find the way. We wait while their leader and Phunchok go looking for the right way. When they find the pass fifteen minutes later, everybody is relieved. We get to the rim where a pile of stones marks the pass. The wrong pass. The real one is a few minutes further down, we've been walking too far up. The strategy was to walk up as high as possible so we wouldn't miss the pass, and it worked, although it was very strenous.

Everybody is extremely happy on the way down. We all seem to know that we've just gotten out of a dangerous situation. Situations like this either break groups apart or make them stronger. The joking and snowball fights indicate the latter. But we do have a couple of problems: the amount of snow is still enormous and doesn't decrease, which makes it a slippery and slow walk; it's five o'clock already which leaves us only two hours to find a camp site; everybody seems to reach or to have reached their physical limit (people slip or stumble, luckily nobody falls down the valley), the cook is seriously sick, one horse leaves a blood trail (though I don't know how serious the injury is, it might be nothing), another horse is about to die. We pass the camp site where we've planned to stay tonight, but there's too much snow. We have one hour left, Phunchok says there's another campsite further down that can be reached before it gets dark. We've been walking for 8 hours without a break at high altitude, I hope everybody can make it there. The sick horse can't. It just lies down to die. I can't watch and follow the other group. We get to a flat spot, they tell me to stay here and they walk on.

It's getting dark, it's foggy and I wait alone in the middle of nowhere. The clouds just hang there in the valley, it seems impossible to think we could have good weather for the next few days. I've walked for over nine hours, had one litre of water to drink during the whole day, my shoes and pants are soaked. I sit on a stone on a snowfield, our campsite, and have time to think. It's hard to grasp the essence of what's going on in my head, and even harder to write it down. I just wish I could be more articulate and describe what has been happening since this morning in a way that I can read it in a year, to have stepped back and re-experienced it all again. But I can't, the thoughts seem to be there for a second only and then make room for another thought. One the one hand I hate this day, but on the other hand I love it because it's physically and psychologically the hardest thing I've done in a long time. Situations like this help you grow and become more mature, I think. But not only that, it also makes you realize how lucky you are when you are in a better situation.

Snow is a foot high at the camp site. We put up the tents without removing any snow, it's not necessary everybody tells me. I'm skeptical - hopefully they're right. I crawl into my sleeping bag and to try to warm up, rest, relax and sleep. Dinner is a bowl of rice and a cup of tea. I go to sleep, after few minutes I can feel the snow melting under me. Where does the water go? This bothers me more than it should, since only a little gets into the tent. But it's hard to lie on the small insulation matress all the time and not roll into the water. And it's really, really cold. I've finally figured out how to use the sleeping bag (I've never owned such a high-tech sleeping bag), only my nose is peeping out of it. But it can't stop the cold from the ground. I wake up several times and am glad when I fall asleep again, this is the best way to escape the freezing temperatures. It's a miracle that I don't get sick. I guess the body knows when it can afford to be sick and when not.

What will the next day bring? I'm very curious.

Ramjuk to Zanskar Sumdo

In the early morning it's way below 0° C. An hour later I open the tent, expecting the worst. But the weather is fantastic, dark blue sky with a few clouds, the intensity of the sun at half past seven is insane. My first thought is what bad luck we've had. If only we had waited another day! This regret haunts me for the next three hours, I don't seem to be able to think about anything else.

In big contrast to the perfect weather are the 'casualties' of yesterday: one horse died; the two ponymen, Indhar and Gabi are snowblind, the horses had to stand in the cold the whole night and couldn't eat anything because the snow was too high. It's a disaster.

We pack our things, put the blind people on horses and go. The cook has left earlier to go ahead but I don't know how he can see anything, the other blind persons can't even open their eyes. The sun melts the snow fast, further down flowers look out of the snow and soon all the snow is gone. The horses and mules stop every few minutes to eat, which is understandable since they haven't eaten anything for a whole days, but we have to walk on. There'll be more grass at the campsite. I still feel bitter that we crossed the path too early. I don't blame anything except my luck. But I was one of those who didn't want to wait. And nobody could've known the weather would change so dramatically. It might have got worse, it might have snowed even more, thus making a crossing impossible. At noon it's still sunny, all the clouds drift into the direction of Shingo La and one hour later it's very cloudy up there. So maybe it was the right decision to go yesterday. I've come to terms with what happened, though I feel very bad for the boy who lost his own horse; it was his only one. But it was sick before and I can't understand that he didn't leave it in one of the villages. They're are going back the same way and he could've picked it up then.

We meet a group of Italians who are going up to the pass. 'We' is what I imagine Napoleon's army fleeing from Russia looked like. The leading guy is snowblind, he's followed by emaciated, overloaded horses with two snow blind people siting on the same horse and the fourth one literally lying on another horse. And even the 'healthy' members of the group (which I have the luck to belong to) have a clearly sensitive negative aura. Those poor Italians must think they'll be going through hell and will come out as we did. How many of them will think about turning around when they walk pass the frozen horse? Even though it isn't funny, Manuel and I have to laugh when we imagine their faces.

It becomes more cloudy, but all the clouds are blown to the pass. Ahead of us is a big valley, a broad river cuts it into two halves. Short grass and flowers grow on the opposite river bank. What a perfect camp site. And yes, we're really staying here tonight. Great! But first we have to cross a bridge, not a new one this time. Where the boards are too decayed they put a big stone to close the hole. I've been promoted and as a part-time horseman I drive them to the campsite. I've always had a big respect (ok, fear) of horses. Now I hold the horse with one hand, open the knots with the other hand and unload the luggage and unsaddle the horse. Admittedly, these animals are smaller than normal horses, but nevertheless I think I've conquered another fear.

After the rainy days, camping in this beautiful valley on such a lovely day is terrific! For the first time we are close to high mountains and can actually see them. Surprisingly, we're the only campers. How can this be? Up to this morning even this valley was snow-covered. All the trekkers left yesterday, some of them after waiting three days to cross the pass. But the storm didn't seem as if it would end and they walked back to the road. So we've been very lucky. Sometimes you don't see your luck unless you've seen somebody else's bad luck. I just sit in the sun the whole afternoon and enjoy every moment of doing nothing. I can even convince myself to shave and wash at (not in, it's still too cold for me) the nearby river. Why can't every day be like this?

We've had some stunning morning moods during the trek, but this is the first completely clear evening. The mountains glow in a white colour long after the sun has disappeared, the air cools down and I have the feeling that everything is getting ready for the night. It's not just the animals that become more and more quiet, even plants and mountains seem calmer and turn silent after dusk. It looks as if things are retreating for a few hours, only to be back in all their magnificence in the morning.

Zanskar Sumdo to Darcha

And how amazing this morning is! I wake up shortly before sunrise, five minutes later the summits in the far distance glow in an orange colour which slowly turns into yellow. More and more of the mountains are 'illuminated', while the valley itself lies in darkness. Above everything is the dark blue sky. This contrast is amazing, and every ten minutes the scenery looks different.

It's been a very cold night, even colder than yesterday on the snow field. That's the reason for me getting up so early, but after seeing the sunrise I'm glad that the cold made me leave the tent. At breakfast the valley is still in the shade, it's really, really cold. By the time we finish breakfast our horses are here and we're glad to start walking. Once again we follow a river, but this time downwards. It's an absolutely clear day, far away we can see the mountains behind Darcha, which is our destination for today. It's a seven hour walk. The first hour the path goes through fields of big boulders, but they make place for flowers and grass further down. The sun is very strong up here, but the wind makes walking pleasant. I feel like I could hike forever, the last three rainy days are forgotten. I wish this wasn't the last day.

We pass a few fields with beans or peas and reach Palamo at noon. This is the place we were supposed to camp yesterday but couldn't reach because of the napoleonesque state of our group. Although it more than doubles today's walk, I'm glad we stayed at Zanskar Sumdo. That place was terrific, Palamo is 'only' nice. The river disappears into a narrow, deep gorge here; it's unbelievable that so much water can flow through such a small riverbed. The bridge is also impressive, it's simply two iron bars with boards laid on top. I can hear the river 50 feet below, the rush is enormous. But I don't spend more time on the bridge than necessary, though it seems to be built solidly. But the lack of a handrail is a bit scary. A false step would be fatal, I guess. But the bridge is wide enough, it's not dangerous at all. I doubt that the horses want to go over that bridge, though.

On the other side a road leads to Darcha. It'd be wide enough for cars, but in the last four days of rain it has been destroyed in several places. It's still good for walking and after three hours Darcha valley is in sight. It's amazing how far you can walk in a few hours. We've walked from one end of the valley to the other. This might not be far in kilometres, but it's as far as we could see this morning. 500 people live in the village, but we camp a bit outside. When I hear this I expect a nice, quiet campsite on the river bank. I'm wrong. We do camp near the river, but close to the road and the main bridge. It's a culture shock, it's dirty, noisy, there are too many trucks and shops along the road. The good camp site is occupied. Why couldn't we stay in one of the villages we've walked through 10 minutes ago? I'm sure this is a idyllic place when you come from Delhi, but after ten days of (relatively) solitary and peaceful trekking and camping it is just too much. This seems an unworthy end to our trip.

I'm a bit depressed, I don't know why. Maybe it's because the trek is finished, and I feel like this exciting holiday is over. I still have four more days, but I consider them 'travel' days and not holidays. Hopefully tomorrow's drive to Manali will offer some great views. Uups, bad news. The road to Manali has also been washed away and has been closed for the last four days. I think about the poor tourists who waited three days to cross the pass, went back to Darcha and sat here for another few days. Nobody knows how long it will take to fix the road. I don't worry about it, I'll get to Delhi in four days somehow. And if not I can take another flight. Phunchok, Indhra and Buphandar have to catch a bus to Leh, their road was just opened today. Somebody from Manali is supposed to bring us a message since there are no telephones here.

Darcha to Manali

It's warm 'down' here (3'300 m), and since the road was closed it was also quiet. Good news, the road was opened last night and a car should get here in the morning to pick us up. During breakfast we can (and I do partially) watch the slaughter of four sheep. It looks cruel, they're beheaded with a single stroke of a machete. Although I've been a vegetarian for more than seven years, it doesn't move me very much. Of course I'm sorry for the animal but it doesn't make me angry. I'm not sure if people up here can really survive without meat. And the sheep had a nice life: in summer they could graze in the mountains and only in winter were they kept in stables. Some people in our group who eat meat can't watch or shake their head in disapproval. How can they eat meat when they can't bear the killing?

The jeep is here and it's time to say good-bye. It's a bit of a sad feeling. We've been through quite a lot in the last two weeks, so knowing that I won't see them anymore feels strange. Since we've been a small group we've had a lot of contact with the local guides. After four days the distance between 'them' and 'us tourists' became smaller.

The jeep driver is a young Indian who wears a bandana, smokes western cigarettes and tries very hard to act really cool. Nevertheless, a fumigating stick burns in the car, a picture of a Hindu god stands on the instrument panel and before he starts the engine he prays for a few seconds. After only ten minutes the damages on the road can be seen. When it rained for several days, small creeks turned into rivers and washed away entire parts of the road. Landslides did huge damage, too. People are busy repairing the road, but there are no road machines. Except for the explosions and the transport of material, everything is done by hand. Everything means clearing the road of stones, hammering stones into smaller pieces if necessary, piling up the stones, putting them on lorries, putting them on a pile after unloading the lorry, cementing the street etc. Entire villages seem to be working as a roadmen or -women, from the twelve year old boy to the seventy year old grandmother. They don't seem to be as happy as the people further north who make a living as farmers.

There are many towns along the road but they're all depressing as hell. Small shops sell toilet paper, coke and cookies; many people just sit there and watch traffic and small children play in the dirt. Those villages seem useless and unnecessary. I'm sorry for the people who live here and even more so for those who have moved here because they thought it would be better here than in the countryside.

Farmers in Ladakh and remote Zanskar might be poorer than people here, but because the farmers have nice houses, fields, cattle and enough food I've never thought of them as being poor. And I doubt that they think of themselves as being poor. Inevitably tourism will show those people what they don't have and can't afford to buy. This will make them poorer in their eyes and is an argument against travelling in such countries.

The brick buildings with corrogated sheet iron roofs are plain ugly. Maybe the rain washed away the whitewash and it looks nicer under normal circumstances, but after seeing so many picturesque villages this makes me remember that India is still a poor country. Most of the road has been fixed, but occasionally traffic jams occur. The road to Rohtang La has been washed away over a long distance. We have to get out and walk, but the car gets through. The drive is pretty interesting, with attractions such as waterfalls, glaciers and high mountains. After four hours we're on top of the pass, the difference between the two sides is amazing. On the northern side we've seen no trees, just flowers and grass.

The flora in Kulu valley on the southern side is totally different. I've never seen such a diversity of trees and flowers, they all come in all colours, sizes and shapes. It's like being on a different continent. We drive along a zigzag road down from 4000 m to 2000 m, which takes over an hour. Thanks to the trees which prevent landslides, the road here isn't damaged at all. Roadworks are going on in one curve, where they are cutting a way through a 15-feet-high snow field which goes across the road. Down in the valley the devastation is incredible. 2 km before Manali the river has washed away entire houses and large parts of the road are missing. We have to walk. Many porters wait to carry luggage and all kinds of other goods, one small guy takes all our three bags at once. The 40 kg and the heat are too much for him, so after half the distance he can't carry my bag anymore. The army is repairing the street with heavy bulldozers, loud detonations can be heard and felt. This seems to be a major attraction for the local people, each roadworker has a few spectators and the driver of the biggest bulldozer could fill a stadium, well, almost...

Manali is very, very touristy. It's not only a place for tourists, the Indian upperclass also likes to spend their holidays up here. I wonder it there are any buildings which aren't shops, hotels, guesthouses or restaurants. There are so many shops that I wonder how the owners can make a living. Soon we get to our hotel and after all the cheap hotels I've just seen I'm a bit afraid. I don't usually care about the quality of hotels, but after two weeks in a tent I either want to have a very nice room or stay in a tent again. Johnson's Lodge is wonderful. It's quite small, has a lovely garden and big comfortable wooden rooms, plus a hot shower, which is what's most important right now. Well, the first shower is lukewarm because I don't notice that I have to turn on the boiler. The second shower is burning hot, a real luxury after the ice cold glacier water.

It's quite hot here, but not too humid. With the nice breeze and the shade of an apple-tree, it feels like being at the sea in Spain or France in summer. I spend the rest of the day relaxing in the garden.

|

Summary Part 3:

The green valley before Kargiakh is soon covered in mist that luckily don't lessen the great the play of colours with white houses, green fields and red hills. After two days in heavy soaking rain we take the chance and start crossing Shingo La, a 5'000 meters pass seperating Zanskar from the lower parts of Kashmir. After almost getting lost in the snowstorm, we put up tents in a desolate valley and spend a cold night there. In better weather we walk down to Zanskar Sumdo and follow a river to Darcha, where we take a bus and head to busy Manali. Despite the luxurious life there I wish I were back in the rugged mountains and valleys of the Indian Himalayas. |