MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

At first the Yangma valley is narrow and densely covered by forest,

higher up it will flatten and be barren.

The white of the mountains literally shines out between the dark pretty fir trees.

Sarphu is not very high, but the bizarre snow figures turn it into an outstanding mountain range.

Strong winds higher up.

Higher up in the valley, the mountains to the east become more numerous and more elegant - sun, wind and snow have created pieces of art.

A long mani wall announces the village of Yangma.

After passing the Mani wall in the flat glacial valley it is just another hour to the village at the end of the valley.

Chorten ahead of Yangma.

The houses of Yangma are built on the amphiteatrical slope above the glacial

plain. A monastery overlooks the village.

We set up camp below the village on the glacial plain - a perfect site to camp and watch the yak caravans on their way to the village.

Yaks are the only form of transportation and used for trading or carrying firewood.

Peaks surround the village and form the border to Tibet.

Since there is no school in Yangma, well, no schoolteacher to be precise,

the kids either go to Pholey for education or stay here for minor work.

Sunrise on the Nubuk peak in the north.

Yaks grazing on the pastures above Yangma.

View of Nupchu from a little hill high above Yangma.

From the glacial lake I follow the creek down back to the village.

Ruins of a fort or monastery east of the village.

Small lake on the way to Omni Kang Ri.

The most stunning peak in the area - Dangpo peak with its delicate flutes is connected to another peak by a long horizontal ridge.

Kangchenjunga Olung: Olungchungkola - Yangma - Chulima Himal

Olungchungkola - Yangma

Olungchungkola Ė Tiguma (Day 12)

Iíve decided to go on my own to Yangma, the group was fun but going alone to the remote village is more tempting than going with the group to Lhonak. After a very late breakfast we start to sort out the gear and food. Tenba has spread out all the provisions and I feel like a kid in the candystore: I can pick what I want. Dal baht and potatoes are fine with me, I wouldnít need anything else except for some eggs for breakfast and a little soup, but Ang Dami is quite insistent that I also grab some of the luxury items like biscuits and muesli. In the end we need kerosene, kitchen utilities, food for a week for three, two tents, my duffel bag - it all adds up and we need two porters to carry all that.

I was worried that they might be a bit grumpy that they have to leave their friends for a few days, but everything seems to be fine with them. Itís almost noon when we start: Ang Dami as guide and cook, Gyurman as kitchen boy, and the Tamang porters Mangal and Mahankali.

On the way out of town I pass the school where kids are playing in the courtyard. The teacher has Tibetan features and probably comes from the area. Maybe itís due to her commitment that the school isnít closed Ė Maoists have come up and burned down the police and tax station but didnít do anything against the school. Just when the bell rings I see the porters are at the end of the village and I hurry to catch up with them.

The green river, yaks in the meadows and the red monastery are a fine last view before we reach the forest and Olungchungkola disappears. The trail is still under construction and we take the route through the bamboo forest where the porters have to be very careful not to slip. Before reaching the junction we follow a branch that climbs up and contours the hillside high above the river that come fromYangma, the Yangma khola. Cows roam in the forest unattended since there is no risk of them going astray. It is so steep that the only way is the narrow path weíre on, and every half hour we have to climb over trees that hinder the cows from running away. A thunderstorm is building up in the south; the humidity in combination with the strong sun makes it a strenuous walk. Whoever detected this route was an explorer in his own right: itís a zigzag trail up and down with some tricky bits in between that connect the easier part of the narrow trail in the forest.

In the early afternoon the crew asks if Iím hungry. Iím not and rather kept going to reach camp before the storm has reached us, but I assume the real questions was: ďWe are hungry, why donít we stop hereĒ. Leaving the trail we climb down to a little plateau over the raging river, a spectacular place to rest for an hour.

After lunch we pack up quickly to get as far as possible today since tomorrow would otherwise be another mission day. I sometimes wonder how the early explorers covered so much ground, regularly they achieve double-marches; of course they were tougher but maybe back then the trails were in better use and condition. Compared to the Olungchung valley this one seems much younger: the walls are steeper and very unstable, thereís hardly a long stretch without any major rockslide areas. The river has run in a narrow gorge so far, now it opens up a little and the walls are less steep. The sky has turned gray, it starts dripping and I happily consent to set up camp early. Between some boulders is some space for our tents, once in the sleeping bag Iím too lazy to get up for dinner but donít want to eat alone in the tent, so I get up and join the crew. Ang Dami has cleared their stuff and cooked in the tent, itís much more basic than the last few nights but very comfortable. As usual my promise that Iíll be fine with just dal baht is not believed by the cook. Ang Dami cooked twice, first sandwich for me, and then the regular staple diet for the porters and himself. The porters have known each other for a long time, and treat each other with less formality than the Sherpas. I guess in this combination these four have not worked together before. It just takes time to get to know each other. The crew waits till I have finished eating, since thereís not enough space in the tent so I quickly go to bed after dinner.

Tiguma - Yangma (Day 13)

The tent stood a little uneven on the stony ground, once asleep it doesnít bother me and I enjoy eleven relaxing hours until the moment a yak trips over the tent string. Itís rather chilly and the sun will still take some time to rise over the ridges of the Sarphu range. The porters and Ang Dami were pretty cold in their tent.

We hurry and after a quick breakfast are on the trail early, trying to shake the cold off while walking through a pine and rhododendron forests. Apart from the trickling of tiny rivulets and the occasional fall of some leaves it is strangely quiet. Only when the sun has started to warm up, and steam is coming from the moss-covered trunks, does nature seem to wake up. When hearing the chirping of birds I realize that their absence largely created the eerie feeling. Tomtits with dark blue feathers and bigger red-bodied birds warm up in the branches. Ugly clearings in the forest are the first indication of humans, large trunks rot unused around though the deforestation cannot be blamed for the huge devastation caused by landslides. Entire hillsides have collapsed and boulders are reaching down into the river. Most of them look pretty fresh, I guess each monsoon season takes its toll. When the walls are less steep and the valley starts to open up the strange atmosphere of the morning is gone; through juniper bushes blinks the white snow of the Sarphu mountains. The range has been getting higher since this morning, the precipitous walls getting more and more snow. They culminate in fine peak of Sarphu II (or III?) whose summit looks like a finely chiseled figure against the dark blue sky.

I stop often to enjoy the great scenery. The (relatively) lightly laden porters are walking much faster than usual, so I often lose sight of them. Since the trail is difficult to detect itís with a bit of luck that I catch up with them before the trail gets more confusing. Small rivulets run over the shadowy path, and juniper trees grow between the dark boulders. This makes the walk up to the crest of the ancient moraine very pleasant. Between the dark green junipers shine the steep white flanks of the Sarphu. The moraine wall must have blocked a glacial lake a long time ago. More and more peaks gets revealed as we climb up. The bizarre snow figures of the Sarphu range stand out against the dark blue sky. [After having a closer look at Hookerís journal (back home) and the illustrations I realize that when he was there 1840, the moraine wall was largely intact http://www.gutenberg.net/cdproject/cd/etext04/hmjnc11h/chap10.html#page 232] The force of the water has burst through the stonewall and ripped it away in the middle. Now I know where these black boulders further in the valley came from. Iím very curious to see what to find after the pass, and I wonít be disappointed. It introduces completely different scenery. Instead of dense forests and wild creeks, the valley floor is wide and completely flat, the river now calmly meandering in its wide bed. Scrub grows on the gentle hillside that is dotted by black chisseled rocks that fell from the craggy ridges. It is quite windy and chilly at the lunch spot, but the sun is shining fiercely. Across the river, the glacier of Zedangchu crawls down in its steep bed. A yak herd is going north just under it. The fine summits rise high into the sky above. Watching scenes like these make trekking so enjoyable.

The walk in the wide riverbed is the easiest part of the entire trek so far. A little path leads through the pebbles and the strong wind is coming from the south Ė going the other way in the afternoon would be unpleasant.

The mountains grow not only in height and size, but also in the number of intricate ridges and snow formations. Drifts of powder snow are blown from the exposed ridges, what a difference to the flat piece of land weíre currently walking on. Suddenly the landscape changes when we climb over the remains of another ancient moraine. The river has now eaten itself into the ground and gnawed on its unstable walls. Though the weather has been fine for some days, thereís a little rock fall. The river is still digging its own way at the bottom of the glacier that has melted long time ago. On the other side of the now unfordable river lies the hamlet of Nup (Tibetan for ďwestĒ), the three houses are built in a classical Tibetan way with flat roof and large walls around them. All the other in the area have shingled roofs and wooden walls.

Another moraine wall blocks the view of the valley ahead over which towers a strange looking peak: a glacier covers the flat summit plateau and steep natural cairns stand on the ridge. After climbing a last small hill we see a large gray chorten that dominates the valley and looks like a guard of the entrance to it. A long maniwall precedes it. Most of the stones are so old that the mantras are barely visible anymore. Since there is no wood to cover the wall people of Yangma have cut out patches of grass and used them as roofs to protect the stones. From the chorten we can see the two dozen houses at the junction of two side valleys built on the slope above the flat ablation valley. A temple stands at the highest points and overlooks the houses. The terraces below the village are fields of potatoes and the stubbles from barley. The flat bottom is used for grazing.

I join Ang Dami who drops his loads and goes up to the village, trying to find potatoes in the village. Nobody seems to be around, but some children lead us to the house where people have gathered. After hitting my head on a low door my eyes get used to the darkness and enter the living room: the contours of man show against the light that comes from three small windows. It takes some time until I notice the women who sit near the fire and tend the pots. They drink Tibetan tea out of china cups. The men enjoy tongba from the wooden vessels. At first I take the gathering for a religious ceremony, some of the men have haircuts that remind me of nagpas (lay priests) but then I realize that itís just a very wild and unorthodox haircut. And the strange guttural noise comes from the stable below.

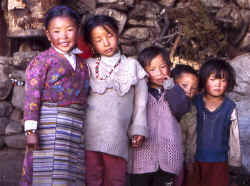

I was warned that Yangma is a poor and sad village. My first impression is that it is definitely poorer than Olungchungkola, the house are smaller and the school less robustly built. However, I did not see any sign of dejection or destitution. Considering that itís 800 meters higher than Olungchungkola and does not have any forest nearby and a pass that has become too difficult for trading, people seem to be doing fine. The children look quite healthy but are very shy.

We set up camp near the school where I also spend the rest of the afternoon. Once the sun has disappeared behind the mountains - early as usual - it is rather chilly already. The cold wind that has blown since noon now moves thick fog up. The nearby peaks are hidden. Further south where the mist has dissolved a range catches the golden rays of the setting sun.

The crews prefers to stay in the tent, and donít want to stay in one of the houses. After dinner, Tibetan soup with potatoes, vegetables and dough balls, Iím off to my own tent.

Yangma Ė Cheche Pokhari (Day 14)

Dogs were barking the whole night, my earplugs froze and even after unfreezing them they didnít soften the noise. Eventually even they get tired and sleep until sunrise. I doze for a while, listening to the murmuring in the crewís tent and the noise from yaks that must be somewhere around the tent. The color of the sky undergoes constant changes as the sun rises. Suspecting that the range that forms the border in the northern valley will have a great color I hurry up the hill but arrive too late. The colors are still nice yet the magic moment when a single point of light appears on the summit and the valley lies in darkness is over. Tomorrow Iíll have to set the alarm clock. Right now the glaciers appear in a dark yellow and contrast with the black rock below and the blue sky above. I spend almost an hour on the hill overlooking the village. Nupchu looks nice in the light and once the sun reaches the village it turns to life. Fires are restarted in the houses, smoke comes out of the roofs, and yaks are driven to the grazing area or tethered to the ground and loaded.

I could probably spend a week here without getting bored, walking up all the side valleys. But I only have two days and be picky: one day for the valley to the north where Jamie walked up to a pass last year, and though I wonít be able to reach the pass thereís a lake worth visiting. On the way I pass the gompa, it is locked and nobody around has a key. Most men are away for work. The children and women are very shy.

On the plateau above are a few lhatos, stone piles with prayerflags that offer protection. The mani stones are covered by lichen and the scripts barely readable. Small trails lead out of the village to the grazing area. There must a lower trail along the river, I stick to the higher route which crosses the plateau where a dozen yaks feed on the open patches between the snow. A landslide marks the end of the grazing and since it is quite unstable there are only two options: cross at the very bottom or climb higher. Itís covered by shrubs and high grass but quite steep and hard to get into a rhythm. I have longed passed the landslide but continue to climb, I must be close to 5í000 meters on the ridge that is mostly free of snow. Yangma is not visible anymore, the Sarphu range dominates the view southwards, the fine summits that Iíve seen two days ago are just the icing on the cake: steep rock faces build the foundation with glacier in between and thin ridges lead higher to the white summits where wind has created fine figures. To the north is the range that forms the border, not very high but still unsurpassable for except one remote pass that is not used by locals (anymore?) and was crossed by foreigners just last year. At the bottom of the valley lies the slightly turquoise lake. Getting further than the lake it out of question, to the lake should be easy. But itís not. The north-facing slopes are covered by a thick layer of wet snow, traversing is tiring and tricky, preventing slips takes additional time. I sink in to my waist a few times, and the snow-covered rockslides are quite frequent if not wider than 10 meters. When I reach the valley floor my legs are tired and feet wet. Large boulders lie scattered around, between them there is either 3 inches of snow or 2 feet and thereís no way of finding how before stepping on it. Several creeks from the Nanggama lake in the east flow in and force me to do some detours. Finally the strong turquoise of the lake appears and Iím at the shore. Its waters stretch far to the north, the opposite shore is completely snowed in and a few small trees look out of it. The outflow is wide and without bridge impossible to cross, so I rest on the small boulder and have a snack. I hoped to see some animals or at least see spurs but the presence of yaks must have driven them into one of the really remote valleys. The views are nice but I donít stay very long, because I started very late and it has taken me three hours. Hoping on finding a trail further down I follow the creek whose banks are often free of snow. I find a small trail and eventually I climb up the moraine wall and am at camp 1 Ĺ hours later. The last few precious minutes of sunshine are wasted for washing and relaxing.

When the sun is about to set, the peaks in the south are again out of the mist and the soft pink summits appear for few minutes. Very soon after that it clears, after dinner the stars shine brightly and illuminate the mountains.

Itís just in the morning that I remember the commotion from night: I wake up horrified to yelling and screaming from the other tent, then somebody opens the tent and hear the stamping of footsteps and the howling. It wasnít a dream I realize much later. Two dogs sneaked into the tent, ate some of our food and even lied down to sleep there until much later one of the crew finally noticed them. Most of the meat has disappeared, but the crew only laughs about it. I give them money to compensate for the loss.

Yangma Ė Chulima Himal (Day 15)

This will be as glorious a day as I could imagine, filled with everything that makes me go trekking over and over again.

I wake up before the alarm rings. The sky in the south is turning into a whitish light blue, while itís gray in the north. Itís high time to pack the camera, put on down jacket and look for a place to watch the sun hitting the mountains. A minute after having found a good spot the very top of Senup peak catches the rays. Itís not a particularly splendid peak but the soft reddish colors makes it stand out from everything else. As the lower parts get the orange color, the rest of the valley is still in darkness. Second Nobuk turns orange, and then the entire range is brightly lit. The ridges of the peaks to the east appear as thin orange lines that separate the white snow from the blue sky. After an hour a cold wind makes me crawl back into the sleeping bag. I doze off and ignore the first two calls for breakfast. Cheese omelet and tasty flat potato bread are a good reason to finally get up.

I laze around camp for the rest of the morning enjoying the warm sun, then ask for two bowls of hot water for a complete shower and then use the remaining water for laundry. My shoes have dried and at 11.00 Iím ready to start todayís walk towards the Chulima Himal. This sidevalley to the east looks interesting on the map, and the peaks I saw from above the village beg for closer inspection. Omni Kang Ri is a symmetrical peak with beautiful ridges and flutes. Maybe I can make it to its base camp.

More barley fields were constructed in the east, but they soon end and a chorten announces the end of the village. A gentle climbs starts along the creek. A mineral in the water has turned the rocks orange.

Two women are collecting the fallen leaves from the small bushes, an indication of how wisely resources have to be used here. An isolated hut and a long stone fence definitely mark the end of the villageís grazing ground. I wonder if the wall is keep yaks in, or predators out. Only a small trail winds itself through a field of large dark boulders for half an hour, followed by flat hollow 20 meters below. A cleft to the north goes to Syao Kang via the Phujang valley. The wide valley continues eastwards toward the Chulima Himal. Some miles ahead it narrows and turns from a dead moraine into a living glacier. A dilapidated fort overlooks this junction. Both the structure and building material indicate that this was not a regular house. Instead of small and few windows it had lots of small openings and on each side three large arrow slits. The lower part was built with stones, the upper with mud, but only two of the outer walls remained. Though on a smaller scale, it looks like the forts built in Tibet and Mustang some centuries ago by feudal kings as a check posts for trading. I have never seen or heard about forts in eastern Nepal, and the location is strange. If it was a local king he should have built it where the village is, if it was a trading post it should stand near the way to the pass to Tibet and not in this sidevalley. Large ancient mani walls are piled up around the fort, so it must have been an important route because I canít imagine that yak herders put up these walls on the way to the grazing areas. Maybe it was a monastery? I donít find anyone in the village who could explain it to me. Chandra Dasí report might mention something about this, but his book is too difficult to find.

I walk down to the flat and wide valley. As usual, my confidence in jumping the river vanishes as I get closer, in the end the width is larger than my jumping abilities. After some minutes I find a semi-natural bridge that spans the Phujang creek. A few yak tracks lead from the bridge to a settlement of six houses, each with a large stonewalled place in front. Nobody is there, this village is probably only inhabited in summer by yak herders. Endless trails yaks lead through hillside. The ground around the village looks nice and grassy, though after ten minutes itís gets more and more muddy and turns into a swamp after all. Finally I do what I should have done in the first place; climb up high on the slope to reach the yak trails. Once there and some landslides later the walk is easy, and the views simply stunning. Across the snow-covered valley numerous peaks are rising, most impressive Nupchu with a precipitous north face and little tributary ďhillsĒ whose steep icefalls and fine ridges lead to the summit. Dominating the view in the distance are the peaks of Tinjung and Dango Peak. The eye follows the gentle curves of the brown moraine, stops at the glacier that floats like a rough sea of ice around the two peaks, and then follows the delicate ridges to the pointed summits. They are superb peaks on their own with their steep snow crags running from a broad glacier to the top. What turns them into an extraordinary mountain is the additional hanging glacier that connects the two summits. The view evokes emotions of awe, but more lasting is a feeling of humbleness.

My goal is to reach the end of the valley and see Omni Kang Ri from closer, but a large rockslide lies ahead, fog is moving in and Iíve reached the turn around time of 14.00. Starting just after 11.00 wasnít a good idea but at least Iím clean and the laundry is done. The next time I turn around Dango is already disappearing behind clouds that are not going to clear this afternoon. Because the mountains are hidden I focus on the grassy hillside and notice a flock of crows that are chasing an eagle. Something else is moving on the slope, two large mammals. The first excitement dies quickly. Itís just two yaks. Some second later I notice two blue sheep 50 meters ahead of the yaks, fleeing from the yaks. I watch for awhile how elegantly the mountain goats tackle the rough terrain. In retrospect it was stupid to watch the blue sheep and not trying to find out why yaks running. Were the yaks fleeing from a predator?

Suddenly thereís a shadow over me Ė an eagle circles 20 meters above me three times and then drifts into the fog without making any noise. As I approach the junction below the summer settlement, a figure appears on the ridge. A large male blue sheep has lead its flock from the Syao valley up the hill. It watches down from the ridge for two minutes. Then a dozen blue sheep follow and graze near the top. Ten minutes later another flock joins them, some of the young goats staging mock-fights, while the others slowly move along the hillside.

The weather has not deteriorated yet, but when thick fog is blown up from Yangma I start to move more quickly downwards. Itís difficult to get lost, thereís the river on the one side and a mountain on the other, but it is a strange feeling to wander alone in thick fog in an unknown place at 5í000 meters. Itís a long way back and I have to admit I am relieved when I meet the two chubby-cheeked women who are still picking up fallen leaves. From the village I see the two forlorn tents which will offer comfort - and food - after a long and wonderful excursion.

Before dinner, we get a visit from the village. Three old women represent the local motherís group, and ask for donations. Usually thereís something ďin returnĒ, like a dance or excursion through the village, but they are so shy and feel uncomfortable that I give them a few hundred rupees without being asking many questions. They seem relieved and chat with the crew for a minute, before hurrying back to the village. Medicine and education is whatís needed, they say.. The teacher never even bothered to come up from Taplejung, so even before the Maoists came up the school was deserted. And thereís no healthcare center for days. Later Iím surprised to hear that the motherís group won an award. When plant poachers from Tibet were in the valley to illegally collect rare plant, they ďdressed up their husbands as Nepali policemenĒ, and were successful to drive the poachers away.

I did what I could in two days and am very satisfied, though moving camp up in the eastern valley would have been great if we had one more day. While dozing off, all the scenes from the day play in my head over and over. Iím grateful.

|

Summary Part 4:

The group is joining the main trail to look for peaks to climb. I decide to separate from them for a week to explore the remote village of Yangma. Together with a cook and three porters I walk up further north in a fine alpine valley. The lush forest is soon replaced by the debris and the remnants of glaciers. At first the marvelous snow peaks form the valleys border contrast nicely with the fine fir trees. When the vegetation gets sparser nothing hides the view of the stunning peaks. After two days we reach the remotest village in the district - Yangma. The simple houses stand on the amphitheatrical hillside above the flat glacial plain where we camp for three nights. Tourists were just last year allowed to visit it, and the locals are not used to guests and very shy. Two valleys meet here, I walk both the northern and eastern valleys up for a day each. Snow prevents me from getting further north than the turquoise lake of Cheche, but it's a worthwile site. On the way to the east I pass a dilapidated fort which leaves me guessing about the history of the village. The end of the valley is marked by a most stunning peak, Dango. Sidevalleys to the north would be worth exploring, but that's for future grous because I have to get back to the main trail to meet my group. |