MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

The wealth shows in the construction of houses,

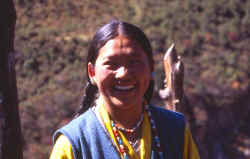

Kids enjoy a day without school.

Gentians peak out between patches of snow.

Large plants protect themselves against the cold with hairy leaves (Meconopsis paniculata).

The vegetation changes on the way from Olung to Mauwa.

Yaks carrying goods from the pastures down to

Olungchungkola, unnamed 5'000 m in the background.

Caravan brings goods from higher up to the village.

The lead yak is decorated with pieces of cloth and bells.

A day above the village snow has fallen and covers the pastures.

Desite being given shoes, the porters still walk in their slippers.

Ghanglung peak, not even 6'000 meters high but very impressive with the glaciers that seem to flow from its summit. This sidevalley takes us to Tipta La, we're the first foreigners since 1840 when Sir Joseph Hooker climbed the passed on his journey through the eastern Himalayas.

View from Tipta La pass back towards Nepal.

View from Tipta La to Tibet, the road is just a day away and people bring modern goods into Nepal.

After a long way up to the pass the descent to camp takes

hours in foggy weather.

Kangchenjunga Olung: Olungchungkola - Tipta La (Tibet)

Olungchungkola - Tibet - Olung

Olungchungkola- Dingsamba Khola (Day 8)

Though we've just arrived, one thing is clear already: Our appetite for exploration exceeds our amount of time. We all agree to walk further up the valley to the north. The map shows some lakes, mountains and passes, but we don’t really know what to expect there. Since we've slept at 3'200 meters we shouldn't gain a lot of altitude today and decide on a late start.

After a short detour to the monastery I walk around the village. Stacking up wood is the major activity, the trading season seems over and the yaks are used to carry logs. The men are in the forest, and most of the women busy with household work so it is difficult to find people for a chat.

After lunch we start and follow the river that runs between red bushes and green firs. After an hour the walls get steeper. On our side in the form of high cliffs, across the river it is less steep and thick forest covers the flank up to the ridge. Some of the rockslide areas we pass look very unstable. Out of curiosity I look more closely at some fist-sized white stones with dark stripes, and I smash them. I’m very surprised to find garnet in them and start looking more closely. Quickly I’m the last as the others pass me.

The walking is strenuous, probably due to the altitude. Quite suddenly fogs moves in from the north, in the eerie atmosphere the tall trees seem to come out and disappear constantly. The sun is a bright circle over the forest, lichen moves in the wind and trees a like figures that play hide and seek in the mist. We meet two locals on their way to a grazing area with three yaks. I want to take a close-up of a yak, and grab the camera the wrong way. The top of the lens pops off. It doesn’t go back in, and I keep cursing the rest of the walk to camp. (The next morning I somehow manage to fix it. I was always very happy with my Nikon F65, but maybe I should look at the more solid versions).

At various places prayerflags and khatas are wrapped around trees, probably offerings to local deities. At the foot of a snow covered peak the river bends to the east, and a smaller valley continues further north. Smoke and bells come from the little grazing camp there, and the little yak caravan is heading there.

We have gained enough altitude for today and start looking for a site to camp. The ground is covered by large black boulders but we easily find half a dozen spots. They’re far away from each other but we’re all tired and happy to get some rest. By the time the porters have arrived, it's close to dusk but still early enough for some laden yaks to pass us on their journey from the grazing area back to Olungchungkola.

Dingsamba Khola – Mauma Kharka (Day 9)

I get up before the sun hits and join the porters who are up already. After the warmth of the sleeping bag I’m as eager as them for the rays to rise above the ridge. When the sun hits, the scenery looks quite different from yesterday. Instead of a gloomy (though attractive) valley we can see the mountains that are covered by a thin layer of snow that looks like powdered sugar. The trees indicate the harsher conditions, it’s interesting to see how the vegetation changes with every day. The sun brings out the different colors of the forest, yellow and red tones now dominating instead of green.

At first the path goes through fields of large boulders, some of them with an almost unnatural red color (lichen or minerals), those in the river are orange. When the valley gets wider we pass a small rhododendron forest. The hillside across the river is completely covered by them, the inaccessibility has saved them from logging. In spring when they bloom it must be a stunning sight, especially against the background of snow. A wooden bridge takes us to the other side and through a fine juniper forest where a large variety of small birds are hiding. It might be imagination but I feel I can literally smell the mountains. Gentians are in bloom, the ones that just look out of the snow have not blossomed yet, others have opened up and are just a little smaller and of a paler blue than the ones in the Alps. The valley gently slopes upward; snow-covered mountains rise above them to the left. A large grassy area between the forest and the barren valley is a fine grazing ground where dozens of yaks feed on the yellow grass. In some distance on the barren hillside a loaded caravan is making its way towards us. Half an hour later the bell of the lead-yak announces their arrival. A young couple drives the furry animals with whistling, after a short chat with our crew they disappear in the forest.

A lonely stone hut stands between the gnarled fir trees. An old couple has to drive away an aggressive yak bull before they can invite us in. They live sparsely; in the courtyard they have spread some rice and corn for drying it in the sun. We buy a cheese necklace (dried balls of hard cheese), and hurry to catch up with the others. I take some close-ups of yaks, and they don’t like it. I’m glad I have a 300mm lens. This last house in the valley also marks the end of trees; further on only bushes cover the slope where several parallel tracks were created by yaks. We rest for some minutes to enjoy the surroundings and watch for blue sheep that might have been forced down to the valley from higher up because of the snowfall from last week. We don’t see any.

The snow has melted on the slope we’re walking on, but when we get to the flat bottom of the valley the snow level increases. Though the valley is relatively flat, time could not erase all the signs from the moraines and the trenches and hills make it impossible to see where the crew went. A bridge spans the Tamur river that has become a small creek. Its source is not far from here. We finf footsteps and follow them to a simple tent where two fierce dogs tear on their chain. Despite the snow the yaks are still on the pastures and a young couple watches them.

The kitchen crew has set up the open-air kitchen a few meters away, and already started cooking. Finding spots for our tents takes some time: the flat areas are rare, the ground is wet or snow covered, and the dogs must be out of hearing distance.

It was only a short hike, but the jump in altitude made me tired, so all exploring is postponed to tomorrow. Clouds and fog move in and increase the grandeur of the scenery. To the south small mountains are covered by snow. To the north the mountains are higher but the flanks are too steep to catch much snow, to the east a steep wall with a fissure marks the entry to a side valley that must contain a large glacier that’s eaten its way through the rock. Spectacular peaks rise above the cleft.

Mauma Kharka – Tipta La – Mauma Kharka (Day 10)

We have planned one day of exploring, the easier peaks don’t look very interesting for climbing and would constitute only of a long and hard plod through snow. The pass to Tibet suddenly becomes an option. A local man from Olungchungkola will guide us. After estimating that it will take us 3 hours up and 2 hours down we start after a late breakfast at 9.30.

The cleft in the massive rock wall was formed by the glacier’s outflow. The gorge is seldom wider than 10 feet. We take the path on the hillside. The storm that kept us at Sekathum for a day dropped a large amount of snow that has mostly melted except for the avalanches that have come down. The chorten in a cave is the only sign that people really pass by. This is a major trade route for people from Walung. Our guide has been here some weeks ago and points out two large caves where he sometimes spends the night.

The higher we get the more of the glacial valley is visible. It looks like a pool of snow that is surrounded by steep mountains on all sides with glaciers forming the lake's inflow. Once we’re in the valley the height of the snow indicates the harsher climate than in the kharka we’ve just come from. A stupendous mountain at the end is accompanied by two stunning steep broken glaciers that descend to the beginning of the moraine. The valley resembles an amphitheater as the crevasses give the glacier an impression of stairs. We follow an old moraine and climb slowly up along its flank. It’s hard work to move in the snow.

We’ve been walking for 2 ½ hours and our guide says we’re halfway there. He means it as an encouragement, but the effect it has on me is quite the opposite. Far ahead are barren peaks of reddish rock, to the left of it - out of sight - lies the pass. The difficult part has not even started yet, 500 meters more to climb and the snow gets deeper every few minutes. Luckily my shoes are reasonably dry and my feet not cold yet. Sharon decides to turn around because of possible frostbite, Andy goes down with her. We continue after a lunch break.

The clouds that have formed early in the morning have reached us now and hide some of the mountains, luckily the pass is still clear. For the first minutes after lunch I feel energetic but realize that it won’t last long, soon later I’m struggling to keep up. Except Tremaine and me everybody is acclimatized and also in better shape. Our guide in his cheap Chinese canvas shoes walks as if going for a leisurely stroll on the beach. We follow in their footsteps which makes it a bit easier. I’m tempted to turn around a few times, but the closer we get the more stupid it would be. The only thing I’m really worried about is cold feet. The second worry is that I’ve used up all energy (and maybe even a little more) on the way up. But any thoughts of the descent are pushed aside for the time being.

Only one more climb, a little traverse on a fairly flat part, another climb and another flat part says our guide. Every step is hard. Often the snow is knee deep and I try to use the steps from our guide, Jamie and Nicola. But often I break through and sink into powder snow that is waist-deep. This makes even the flat parts very tiring. The climbs are not less tiring. We come across cat prints in the snow. Our guide saw one snow leopard recently that killed a young goat. Many other prints are likely from blue sheep. There’s also boot prints, probably belonging to Tibetans, who – knowing that nobody will be up here in conditions like these – sneaked to the Nepali side to hunt for musk deer which can be sold expensively for Chinese medicine.

I concentrate on the trail and try to remember another pass that was this difficult. Shingo La during a snowstorm was equally hard, tough more mentally than physically. The high pass near Tso Moriri in Ladakh was also tough but not nearly as hard as this one. Suddenly we face the last obstacle, a gentle slope. The climb is over and we reach an elevation where prayerflags flatter in the wind. Technically speaking we’ve crossed the border and are in Tibet. And we found the source of the Tamur river.

According to our guide we’re the first foreigners on the pass. The area was opened for tourism just recently, and the Chinese side is probably closely guarded. (I’m a bit skeptical and will have to read Hooker’s book to see which pass he reached in 1840. He managed to get it here, his description sounds similar to mine. See his interesting book online, xxx)

This is not one of the classical passes from where we see far into the Tibetan plateau or have a stunning view of huge mountains. The valley makes a sharp right turn and only from there is the high plateau visible. A Chinese road ends at the foot of the mountains and traders pick up wares for trading there. The wind on Tibetan side constantly changes the form of the high clouds that contrast with the dark blue sky. Nothing disturbs the visual effect of complete distance from anything.

However, the existence of Olungchungkola and countless other Tibetan settlements south of the border show that these passes are not as impassable as they seem. The real border seems to be the middle hills with their jungle and steep gorges.

We stay half an hour on the pass, throw the lungta’s I brought in the wind yelling “soso” and “lha gyalho” and start our long way back. After a change of socks my feet feel very warm again and the worry about frostbite proves unfounded. I feel relieved.

The Nepali side of the pass is cloudy now, and fogs starts to hide the lower parts of the glacier. It’s past 3 already, and a long descent lies ahead of us. The first few steps seem very easy compared to the way up, but we have to struggle to get out of the snow when we sink in too deeply. At some stage my body goes into what I call “auto-mode”, the brain is less active and the legs seem move by themselves without requiring attention or any strength. I know I can go on like that for some hours. We reach the lunch spot after a long time and continue without a break until the end of the moraine. As we sit down for a minute we watch the last sunrays hit the top of the unnamed peak that looks out of the clouds. I'm very tired, but fine. Tremaine is on the verge of throwing up.

I increase my speed in order to get as far as possible before it gets dark. Dusk is soon followed by night. Halfway down the gorge it’s dark. Thanks to night vision and a little moonlight it’s easy to find the trail even without torch lights. Shortly before reaching the ablation valley three lights flicker on the path – Tenba sent two Sherpas to look for us with biscuits and hot drinks. Having such a crew is truly amazing, and I think they know how much we appreciate their work.

It’s only a few more minutes to camp: finally in the tent, I change clothes and lie down for ten long, wonderful seconds. I’m too exhausted to be hungry, almost fall asleep at dinner table and quickly go to bed. On the way I almost bump into one of the young yaks which were driven up here during the day.

Mauma Kharka – Olungchungkola (Day 11)

Tonight the dog was either very quiet or I was sleeping like a stone. I wake up after uninterrupted sleep with slightly sore muscles in the morning. That and the slightly increased appetite are the only hints of yesterday’s mission. Jamie organized fresh yak milk, and with a little skepticism I try half a cup: it is very tasty, a strong herbal or flowery taste that I would call “masala milk”. With some clever marketing (and ways of quick transport and hygiene) I’m sure it would sell well. But most of it is probably used for local consumption and cannot be used like the seathorn buck berries in Ladakh (a thorny bush with not much use for locals but plenty of potential as a product for tourists). It’s a splendid day, snow still covers the ground but the sun is warm enough to grant us an open-air breakfast.

The way down is easy, yesterday’s acclimatization and the extra training have helped a lot. Soon we’re crossing the grazing area where we stop to have a last look at the magnificent valley system. We could have spent two more days, going up the Mendolung river but wouldn’t have been able to get to the border, or another day going right from here to the Singjengma valley and its two glacial lakes. Sadly we don’t have unlimited amount of time and want to explore two more valleys to the east. Snow-capped mountains in the background, yaks grazing and the fresh mountain air are a memorable last sight.

At the junction Dingsamba Khola the weather is still fine though a cold wind has picked up. After lunch of dal baht, mist is gathering on the ridges and soon the atmosphere is like on the way up. The gray of the fog increases the colorful bushes and trees, but at the same time makes the rockslide areas look more sinister. I do stop often to look for garnet and do find some fine ones, but not nearly as large as the ones we were offered to buy by the villagers. The last part of the way stretches far longer than I remember, but in the early afternoon I arrive at camp where some of the porters already celebrate the reunion with those who stayed behind.

We go to the guide’s house where the left-behind equipment was stored. His wife invites me for a cup of tea, and with the harsh but not unfriendly resolution brushes aside my excuse of “not feeling well, stomach sick”. A small fire is burning in the hearth and I sit down on the rugs along the window front . Our guide will be out of the house for another week since he agreed to guide us to Ghunsa. The Nango La which we intended to cross received a lot of snow and is blocked. To avoid walking all the way to Sekathum, he suggests using another pass. It is not on the map. He’ll be guiding us and also bringing some of his yaks for carrying loads. The plan is to go up to Lhonak and explore the “hidden glacier”, and maybe climb a peak there. I have been to Lhonak two years earlier and would rather go up the Yangma valley. Jamie is fine with splitting the group, and organizes Ang Dami and two porters to come with me. We agree to meet one week later on Kambachen, and spend some days around Jannu north face base camp.

|

Summary Part 3:

The trading pass lies a few days north of the village. We have enough time for exploration, and leave the town with a local villager who's agreed to show us the way to the Tiptala pass. The autumn colours in the forest indicate a change in vegetation. Alpine flowers look out between the patches of snow that cover the pastures higher up. Yak caravans and simple shelters mark the end of the inhabited country. During the climb to the pass our guide tells us we're the first foreigners up here (apart from J. Hooker in 1840), but the pass isn't reached easily and I'm about to give up after hours of plodding through high snow. Being the first day at real altitude makes it even harder. However, after a tough climb we've reached Tiptala Bhanyjang, 5'xxx meters high and marked by prayerflags. The views into Tibet and back to Nepal are great, but soon we embark on an endless seeming return journey. Dusks sets in while we're still fighting our way through the deep snow. The moon rises and we're still not in camp, but eventually we make it back to the comfort of our tents and enjoy a relaxing sleep after a strenuous but very worthwhile excursion. |