MyHimalayasimpressions from |

|

|||||||

In the lowland the variety of butterflies and their colour increases quickly.

The higher we get the smaller and less colourful are the butterflies.

North of Sekathum the valleys are not inhabited and often it's hard to find enough space for a campsite.

Vertical walls define the Tamur valley, often the trail climbs high above

the torrent.

Up to 3'000 meters the forest is very diverse, autumn

colours of the bushes increase the number of colours.

Relaxing afternoons after a hard trek in the morning.

Porters cross the bridge on the way to Olungchungkola.

Way to Olungchungkola, the monastery is already visible from far away.

Yaks roam around the village, the people are rightfully proud of these

amazing animals.

The wooden houses of Olung spread on a little plateau. The village is

wealthy, despite severed ties to its Tibetan neighbours and the reduced trading

activities.

Porters arriving at camp, dropping their loads and starting

the joking and teasing.

Porters have bought a sheep and prepare their bbq.

The monastery is one of the oldest in Nepal, and though much its treasures

were brought to Kathmandu, there are ample statues and thankgas left to wonder

at.

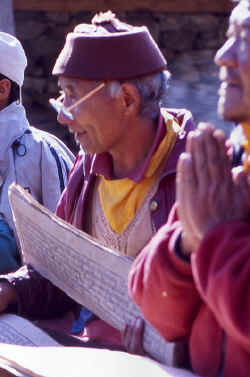

Only five monks live in the monastery, every afternoon they hold a ceremony.

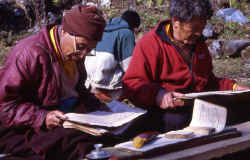

Old books contain the holy scripts, however the old monks know most of the

prayers by heart.

Kangchenjunga Olung: Sekathum - Olungchungkola

Sekathum - Olungchungkola

Sekathum (Day 4)

Rain increases as I fall asleep. Every time I wake up, the sound of raindrops hitting the tent seems to be getting louder. In the early morning, wind comes up which brings in more low hanging clouds and mist. Initially I welcome the wind because it seems to be the only thing that can move the gray cover from the sky. Our hopes are dashed when the wind continues and, instead of helping to clear, brings more and more clouds up. The bright spot closes and gray becomes the dominating color again. The trail and future campsites have probably turned into swamps - if not by now then they will be after our groups has passed - and walking in a downpour is not my liking at all. The decision to postpone departure to the afternoon suits me first. But after hours of lying in the tent, reading, and eating chocolate Iím itching to move. However, a look at the few sodden by-passers that are soaking wet reminds me of the fact that I really am a fair-weather hiker par excellence. It's interesting to note how quickly the regular Western restlessness disappears when trekking: after some time cursing the weather you get used to the thought that it is out of your control. And I stop worrying about it. The moment is perfect as it is: enjoying a nap in the tent, listening to the rain, and the occasional glimpse out of the tent that increases the feeling of complete comfort even more. Iím not alone, my dry tent has turned into an Ark Noah for insects.

Across the river the last monsoon tore down parts of the hillside. The rain that currently collects higher up and runs down in rivulets manages to send down decent sized boulders every few minutes. They land in a big crash near the river, the sound reminds me of fireworks. Our porters cheer, yell and whistle every time a larger load comes down. We tourists are equally interested, and stare for quite some time. What a lazy afternoon.

Some tourists on their way to Suketar arrive soaking wet from Amjilosa. Their porters haven taken the rarely used trail on the other side of the river. Our crew yells at them to run quickly and points at the rock fall. Those who run as quickly as to indicate fear get cheered at and everybody laughs loudly. Five minutes after the last porter crossed, the biggest landslide so far crashes down. Large boulders break into smaller pieces as they hit the floor, some fall into the river.

Tenbaís brother if the official cook, but a few Sherpa assist and the meals are the highlight of the day. After a vegetable pizza I'm ready for bed. Tihar festival is today, as presents the village girls give us some marigold flowers. Porters play music and sing, the girls from the village start dancing and the least shy porters join in. Later most crew member join the dance but at that critical stage Ė the expectation of tourists dancing might arise - I'm already half asleep and walk back to the tent. As I doze off I think about the friendliness and hospitality of Nepali people who, in addition to a hard life now have to worry about their very lives. They are caught between the army and the Maoists, and neither offers opportunities for a better future. Maybe it's the dull weather, but I felt that amidst the happy party was a sense of melancholy and a desperate attempt to forget their situation for some hours. But again, it's likely that this impression is wrong.

Sekathum - Tartong (Day 5)

Patches of blue sky give hope for a better day, though the little drizzle could be an indication of more rain to follow. Nevertheless, we pack up and start after breakfast since the next campsite is not too far away. We climb up from the bridge to the "village" which is situated on a little plateau above the river. Two houses stand in the middle of millet fields. Higher up is a third house whose owner - if all the cows in the gate are his own - must be quite wealthy.

The trail above the river descends to a bridge that spans the wild river that has eaten a deep narrow canyon in the valley. From higher up the whole chasm is filled by whitewater, an impressive sight. Waterfalls punctuate the steep cliffs. There must be something special about this forest, for the first and only time we see green parrots fly around, the color of the feathers makes them invisible when they land in the trees. Patches of mist slowly move along the steep walls, the sun illuminates some houses and terraces and gives the scenery an appearance of a dramatic painting.

The late season-rain and the large number of people mean itís party time for leeches. Some of us get sucked, the reaction ranging from complete ignoring (porters), a shrug and removal (Andy) to a slightly hysteric stampede (Nicola). I spot some of the small creatures while they wriggle their way up on my boot and hiking stick, but have enough time to flick them away before they reach the skin.

The wealthiest village in this valley is Lungthung. A large mani wall stands in the center; a dozen houses are spread out and separated by fields of millet and corn. The people have distinctive Tibetan features and clothing, but they celebrate Tihar like the people further down: the doors are decorated with flowers, the cows carry garlands of marigold around their necks.

Lonely huts occupy the few flat spots in the valley. The fields are very small and cannot possibly support a person let alone an entire family. They're probably just used for storage and spending nights during harvest season.

The next two hours are climbs along steep hillsides, either in the forest or in open spaces. A look up the valley reveals nothing that could suit as a large enough campsite. A last climb takes us up to harvested fields of corn where one of the terraces serves as the campsite. Assuming there is a large village higher up, I go for a walk but find only two small houses. The two families who own the few fields live there. Two other houses were destroyed by landslides and haven't been rebuilt. Live at high altitude seems harsh, but considering the small settlements, it must be even more difficult here. Temperatures are probably better here, but there is hardly any room for agriculture or husbandry, and no oppportunities for trade.

After an early dinner I'm in bed before 20.00. Two hours later it sounds as if hell broke loose. There's noise, commotion, light. Some villagers have come to party. The blurring radio and their singing is not appreciated, I'm not sure if they are more friendly or more drunk, probably the later. I usually appreciate visits by village people who raise some money by dancing and singing, but this cultural show was a bit too rapturous. Jamie yells at them to piss off (I assume), and soon itís quiet again.

Tartong - Jongin (Day 6)

A perfectly sunny morning is the biggest motivation to get moving. Several trail leave the village towards the north, and it is not easy to pick the right one, since there are old and new trails but it's hard to tell which is which. The old upper trail is more spectacular; it climbs up to the ridge and continues on the right side of the river almost all the way to Olungchungkola. After the ticks and leech experience from last year, Jamie advices to try the new trail further down. Parts of it have already been washed away and we cross some muddy gullies where a slip is not recommended. The water of the Tamur comes down in constant cascades, additionally fed by little waterfalls from both sides of the valley. The trail is wide until it reaches a bridge that crosses the torrent. To access the head of the bridge we climb up a shaky looking stair that was built from thousand of stones.

So far we've walked in open space or open forests. The left side of the river gets the sun much later, and the cool temperatures have lead to a much denser vegetation. The narrow path is overgrown in some parts, or just wide enough to walk single file line through the bushes. Often it climbs up steeply between huge moss-covered boulders. The stones laid down by the road builders are often slippery; nevertheless they make walking a bit easier. Forcing a trail through the jungle and placing the stones must be a terribly hard and time-consuming work. The climbs and descents are quite strenuous. Despite the humidity, the weather is great. The sun is still hiding between white clouds and the trees help to retain the morning coolness for a long time. Walking through here in brilliant sunshine or rain would be terrible.

Then the forest becomes less dense, and though it was to interesting to walk in it, there's a bit of relief to get out of the dark and humid jungle. We enter a bamboo forest that is interspersed with tall trees that are less suffocating and offer views: just below us is a 600 feet drop straight down the roaring river, far ahead a craggy mountain with fresh snow rising above the junction of two valleys. The sheer cliffs are hardly visible because no matter how steep they are, vegetation covers them. The threatened Red Panda lives here, but of course they're too shy just to see them along the trail. Compared to these valleys, the 5'000 meter passes to Tibet look easy.

The difficulty of terrain is felt by the complete lack of habitation. The only indication that people pass by is the trail itself and one simple stone hut that offers shelter and shade. Gradually the trail takes us down to the river, the cliffs are less steep and the valley gets wider. Colorful trees dominate the scenery. All the reddish trees are small, something must be have wiped out the older trees a few years ago. The scattered boulders resemble huge marbles, green moss covers them and makes this part of the valley very colorful. After the jungle that consisted of only green, the blue sky and white clouds, red trees and the white water are a welcome change. Gurgling creeks come down the steep side valleys, their source near the crags are hidden in mist. Trees with lichen appear as silhouettes on the ridges that play hide and seek.

We sit down between two branches of a sparkling creek to enjoy a pack lunch. A more perfect place would be hard to imagine. Compared to the last two days the variety of scenery is enormous, and a sense of reaching the 'high lands' adds to the excitement.

After lunch it's only a short walk to camp. It'd be possible to walk straight to Olungchungkola but it would be a long days for porters. Luckily we don't have to rush. And enjoying a lazy afternoon at camp is a fine prospect. A meadow covered by high yellow grass is visible from some distance away, then a lhatso with prayerflags on a little elevation and finally three wooden houses. Our porters have arrived and quickly disappear in the houses to drink some tea and chat with the two only people in the village. The houses seem to be second homes. Inside they're almost empty except for a small hearth, a very reduced altar and some boxes with food and ingredients for tea.

I put up my tent near the lhatso; from the hilltop the views down and up the valley are nice. The sun is still up, a short nap in front of the tent is a good end of a short but strenuous walking day. A breeze makes the hot sun tolerable.

Jongin - Olungchungkola (Day 7)

After a windy night I expect clouds from the south, but the sky is blue. After a week on trail I feel that the best part of the trek begins. A traditional wooden bridge spans the Tamur, then the trail continues on the right bank through a flat area that is covered by boulders and bushes. At a spectacular tunnel-like formation thousands of liters of glacial water roar down every second. A modern bridge crosses the river, the porters prefer to take the old wooden one higher up. Several fields of rockslide need to be crossed. Landslides seem to be common in summer when the rocks becomes unstable due to the water that collects higher up. Now only small rivulets come down from the ridge. At a shady place the porters sit down and cook their 10 o'clock dal baht. Iím a bit envious.

There must be a side valley to the left where the old trading route with Tibet was but I canít see a breach in the valley wall. It looks like we've reached a dead end. But it canít be, since the river must be coming from somewhere. Suddenly a loud noise indicates a waterfall. The water shoots through a 15 feet wide cleft in the wall. We canít follow the river any longer, the path taking a different route now.

Further ahead a massive landslide has taken down the entire trail. Locals are trying to stabilize the wall and, after a short warning, send down loose rocks. A temporary trail crosses the landslide and climbs up through forest. With one eye on the trail and the other watching for rocks I run across the gullies. A steep climb across bamboo forest is difficult for the porters with their bulky baskets. When we hit the wide main trail it is only a few minutes to the pass in the fir forest. Prayerflags and one overgrown lhatso indicate not only the pass, but also beginning of the valley of Olungchungkola. It is a very humble announcement of a most fantastic alpine valley that is stunning both in scenery and culture.

A snowy peak at the horizons is contrasted by dark blue sky, the red and yellow trees in the deciduous forest add to the play of color. On a plateau overlooking the milky blue river stands a large monastery with traditional orange coloured brick walls. The village houses doesn't come in sight until we reach the entrance. Two dozen large shingled houses are built on a plateau below the monastery. Vegetable gardens reach to the edge of the cliff, juniper trees cover the hillside. School must be over (Tihar festival?), children run around in the village and welcome the change of visiting tourists. They are active and loud, but in a very nice manner.

They look very Tibetan, and the village gives a similar impression. However, the people are slightly different than the ethnic groups from Tibet and adjoining areas in Nepal, and are considered a separate indigenous people with their own Tibetan dialect. The entire region is called Olangchung Gola, and consists of the area from Yangma in the far north down to Ghunsa and Lelep in the south. 1í500 people live in those villages. Gola means market, and people used to be mainly traders. The Tibetan border is near, and trade was always very imporant. These days modern Chinese goods are also traded. Raising livestock (yak, horse, sheep) and agriculture (barley, wheat, potatoe) is more important than trading. The highest class of Shiwa consists of seven families (the first inhabitants), but the the two other social groups have equal opportunities.

In the afternoon I walk up to the monastery whose compound is marked by prayerflags and two water-driven prayer wheels. Five monks recite prayers from old scripts; an old lama, and educated looking old monk, a senior monk and two laymen. Somebody from the village stops by every twenty minutes to refill the cups with Tibetan tea. An old woman brings vessels with tongba, a slightly alcoholic mixture of fermented barley and hot water. The monks are from the Nyingmapa sect where drinking is allowed.

Most of our porters are Tamang, and therefore Buddhists. Most of them are looking for the lama for blessings. He interrupts his prayers and leads the porters to the lhakang where he pours blessed water from a silver vessel into their hands. This main room that once served as the assembly hall isn't lit; with a torch I see a big statue of Padmasambhava and Chenrezig. Some thangkas are very old, other look rather brand new. Large horns rest disassembled in a corner, a huge drum also seems to be used on special occasions only. The annual ceremony of cham dances could be such a festival. Some masks hang from the pillars, though there must be more in one the many other rooms. The books of the Kandjur and Tandjur fill the racks on the large wall. Opposite the lama's seat is a low rack with statues, some of which look quite old. They are reflecting the torch light very strongly, could it be real gold? Despite its remoteness it wouldn't be that surprising. I'm in the oldest Buddhist monastery in Nepal (apart from one on the Nepali-Indian border). Most of the treasures were brought to Kathmandu by the Nepali king to "ensure their protection". Art theft is a very big problem in Nepal, but I'm skeptical that this is the right approach. The safest protection is a functioning social system in the village itself.

The monastery must have hosted much more monks in earlier times. Most of the numerous large other rooms are empty. But the room below the shrine room contains more statues and thangkas, all worth a much longer inspection. A sick woman rests in the room, she complains about pain in the knee and elbows. I assume it's arthritis but promise to ask Nicola who is a trained nurse. My diagnosis was wrong. The woman might have caught some disease while traveling on bus through the low land in Nepal's south. She lives in Kathmandu and came for a visit, bringing things for the monastery. There is not much we can do to help her. She has to be brought to a real health station.

When I leave the monastery the sun has already disappeared, not unusual in these north-south facing valleys. Itís too chilly to laze around outside, itís either time to put on the down jacket or spend the two hours to dinner in the sleeping bag. Porters have all chipped in to buy a goat, and are looking forward to their barbeque. Others cook rice on an open fire. We have pasta with tomato sauce and grated cheese instead. But first the regular soup which never taste better than on these cold evenings. I'm in the sleeping bag early.

|

Summary Part 2:

The gorges that lie between the low lands and the Himalayan valleys are spectacular - the rivers rushes through narrow channels while we walk high above it on trails chiselled out of the steep valley walls. Villages are rare, and wildlife has plenty of space to hide in the big bamboo forests. After two days the valley opens up and camp on a clearing above the Tamur river. Just another few hours further north lies the village of Olungchungkola. The prosperous village is overlooked by a large gompa, the oldest monastery in Nepal. In previous times, this was a major trade route to Tibet, till today people live from trade, animal husbandry and a little agriculture. These days the monastery only houses a few monks, but it is still a very impressive compound where some of the statues and thangkas tell of its glorious past. |